Honduras wrestles with poverty and crime at ballot box

- Published

Members of the Mara 18 gang and the Mara Salvatrucha are held in different blocks at the Renaciendo juvenile detention centre

The short drive to Renaciendo juvenile detention centre outside Tegucigalpa is a vivid illustration of the dual challenges facing Honduras.

The first is poverty.

On the outskirts of the capital lie sprawling, chaotic shanty-towns of small brick shacks which snake up the hillsides. Beyond the city limits, the poverty quickly changes in character from urban to rural. The simple homes are made of wood and corrugated iron, many with dirt floors, set in the middle of hectares of banana trees and tropical grasslands.

It is not hard to see why this is the poorest country in the Americas after Haiti.

But it is on arriving at the youth prison that the other main issue in the country becomes clear: violent crime.

Honduras has the highest murder rate in the world. Inside Renaciendo, members of the two main gangs which dominate swathes of this Central American nation are housed in separate prison blocks. The Mara 18 gang on one side, their rivals the Mara Salvatrucha on the other.

The inmates may be young, some barely teenagers, but they have led lives of criminals twice their age. Some are inside for murder, others were hit-men, some disposed of dismembered bodies. Not one of them is older than 17.

Total dedication

As I speak to a group of boys from the Mara 18, they explain how the gang, which they refer to as "The Big Family", means everything to them and demands their total commitment to the cause.

"From a young age, I started to run with the Mara 18," says Luis, though that's not his real name. A sharp-eyed but troubled young man, he is unrepentant about the crimes he has been involved in, saying everything was for the good of his "barrio" or neighbourhood.

Poverty is one of the great problems facing Honduras, with one of the lowest incomes per head in Latin America

"The Mara 18 showed me love and always tried to understand me. We're brothers. The Big Family, you know?"

His cellmate echoes the sentiment of total dedication. "This isn't a game for us. This is serious. The Mara 18 is like our job or our families."

The man who has spent the most time getting to know the gang members since they were arrested is Jose Angel Solano, a youth worker at the jail. He says the fact that a general election is being held on Sunday is meaningless to them.

"For these young people [the election] means absolutely nothing. They live far from the political life of the country, inside their world."

Jose Angel too feels disillusioned by the presidential candidates and their proposals to tackle security in Honduras.

"Every four years we get our hopes up that a new government is going to bring in new ideas, especially for the youth. But we're tired now because four years pass, and then four more and then four more after that, and it's always the same: more poverty, more young people in the streets, more crime."

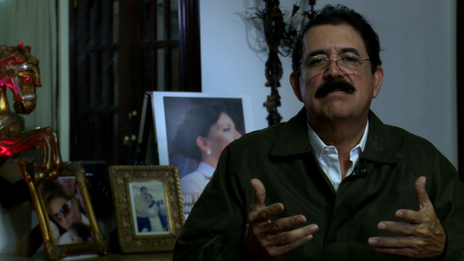

Supporters of Mel Zelaya, who was ousted as president in 2009, are supporting the candidacy of his wife, Xiomara Castro

In many ways, this race has become a chance for two sides to fight out their legitimacy following the moment in contemporary history which caused more social conflict in Honduras than any other - the coup of 2009 which ousted the then-president, Mel Zelaya.

Mr Zelaya's supporters are backing his wife, Xiomara Castro, who is making a bid for the presidency under a newly-formed political party, Libre, in which the ex-president plays a significant role.

"We are not improvising and this isn't about personal aspirations," Mr Zelaya told the BBC at his home in Tegucigalpa. His wife has the credentials to lead the country, he insists, and says the new party is a reaction to the 2009 coup.

Former first lady Xiomara Castro hopes to move back into the presidential palace

"This is a struggle which grew up in the wake of the coup and a revolutionary party which is resisting against violence, against crime, against everything that has happened since the coup d'etat. The people are rising up."

But if the former first lady hopes to move back into the presidential palace, this time as the leader of Honduras, she will have to defeat the candidate of the party which openly backed the coup against her husband. The governing National Party candidate, Juan Orlando Hernandez, was until recently the president of the National Congress.

Despite his party being in power for the last three years as well as many times in the past, he places the blame for the violence, poverty and disenfranchisement in Honduras firmly at the feet of Mel Zelaya.

The National Party candidate for president, Juan Orlando, blames Mel Zelaya for the violence and poverty in Honduras

"Because of the conduct of the previous government and the party now called Libre, Honduras almost became a failed state," Mr Hernandez told the BBC. Since the coup, he argues, the government has put the conditions in place to move the country forward, such as starting to purge the justice system of its links to organised crime.

"I'm an optimist by nature," he says. "I guarantee you that what is on the one hand a crisis, can be seen on the other as a great window of opportunity."

Many people in Honduras, particularly the young, would undoubtedly welcome a genuine "window of opportunity".

However, in a country with one of the lowest GDPs per capita in the Americas, where doctors, teachers and government professionals have gone unpaid for months, with rapidly dwindling foreign currency reserves and spiralling debt, not to mention the high levels of violent crime, they are sceptical that one will emerge any time soon.

- Published31 March 2023

- Published7 August 2013

- Published4 August 2013

- Published10 April 2013