Venezuela emerges from trying year

- Published

Venezuelans have grown used to queuing as basic supplies have grown scarce

It has been a difficult year for Venezuela.

The country faced the absence and death of its divisive president, Hugo Chavez, which resulted in fresh elections, contested results and an economic crisis.

Newly elected President Nicolas Maduro struggled to cope as Mr Chavez's successor, while Venezuelans queued up for milk and toilet paper and were confronted with one of the world's highest inflation rates.

The opposition tried to capitalise on the country's economic woes, hoping to prove that Mr Maduro was an illegitimate leader.

All came to a head on 8 December, when municipal elections were held.

Normally a relatively low-key political event focused on local issues, this month's polls became a face-off to determine which side was stronger.

Official results showed that 54% of the vote went to the government coalition - 10 points more than the opposition coalition, which only got 44%.

This was a surprisingly wide win for the government coalition compared to Mr Maduro's narrow victory of 1.5 percentage points eight months ago.

'Decisive year'

Analysts from both sides of the political spectrum agree that "chavismo" - the distinctive brand of socialism promoted by Mr Chavez - gained important ground.

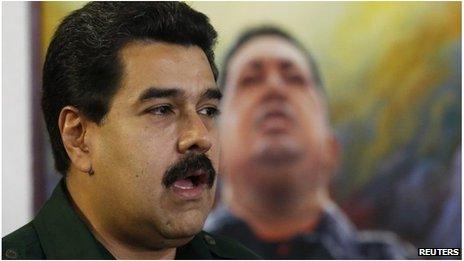

Nicolas Maduro has traded heavily on his close relationship with the late Hugo Chavez

Though many of the problems that marked 2013 are far from being solved, the results cleared political uncertainty from the air, giving Mr Maduro a chance to catch his breath.

"This has been a decisive year to test Chavez's legacy," says Javier Biardeau, a pro-government sociologist at the Central University of Venezuela.

"The local elections have confirmed that chavismo still has historical viability within Venezuela, and that [Mr] Maduro has been accepted within chavismo."

"The government acquired political time and legitimacy that will help it face the economic challenges ahead," Mr Biardeau told BBC News.

At the same time, the opposition coalition won some of the country's largest cities, such as Caracas, Maracaibo, Merida, Valencia and Barquisimeto.

But it was an overall loss for Henrique Capriles, the leader of the MUD opposition coalition, who had called for this election to be a referendum on Mr Maduro.

This leaves the opposition with many pending questions about its future strategies.

There are no elections until 2015, when Venezuelans will pick new delegates to the National Assembly.

In the meantime, the current members of the National Assembly have little wiggle room, as Mr Maduro was granted special powers to pass laws without the Assembly's previous approval.

The opposition wants to gather signatures for a recall referendum which would ask voters whether they want their president to step down. The constitution says this is only possible after the president's first half term in office, which would be 2016.

It seems that there are few options for the opposition at the moment.

Political analyst John Magdaleno believes the opposition needs to do some soul searching before it can move forward.

"How come the opposition hasn't been able to consolidate itself over these past 14 years?" asks Mr Magdaleno.

"The government went through a terribly challenging situation this year, but the opposition was incapable of taking advantage of the situation with enough energy."

Room for improvement

The MUD coalition is made up of 30 parties with different political views, united mainly by their opposition to chavismo.

Henrique Capriles failed to make the hoped-for gains for the opposition

They are careful not to discuss their divisions with the press.

"The MUD is a very ample alliance where there are different positions, but we have always managed to agree on common policies," said Ramon Guillermo Aveledo, MUD's executive secretary.

"The coalition is a perfectible instrument, it can be improved, it can be perfected. We are taking the initiative to speed up this process," Mr Aveledo told Venezuela's Union Radio.

Chavismo has the advantage of having access to the government's resources for spreading its message during the campaign, including the president's daily radio and TV broadcasts.

But while the opposition came close to a victory in April's presidential elections, they had lost momentum by December.

Mr Magdaleno believes that the reason for the opposition's losses are to be found within the opposition itself.

"There is a problem with their discourse," he says, explaining that the opposition is not proposing real change.

"They have been stuck in a spiral of elections, but they need to engage with real politics now."

'A new phase'

December's results were also a victory for Mr Maduro because he managed to change a negative trend in public opinion.

Annual inflation had risen to 54.3% in the final months of the year, becoming one of the highest in the world. In the meantime, food shortages, power outages and a staggering black market exchange rate became daily worries.

The government's economic measures were not popular with the public.

There was a rush on electronic goods after shops were forced to slash their prices

But then in November, Mr Maduro launched a strong offensive against what he called "unscrupulous businessmen". He occupied electronics stores, forcing them to slash prices, just after handing out Christmas bonuses to all government workers.

"These measures had a successful propaganda effect," says Mr Biardeau.

"Maduro was put to the test and he passed it, while building his own profile."

Mr Maduro has held victory speeches since 8 December, saying the municipal elections was a watershed.

"These elections close a cycle and now a new phase starts in our country. We closed a difficult and complex cycle that lasted 14 months," he said.

There are some big challenges ahead for Mr Maduro, especially when it comes to the economy.

But at least, for now, he has proven that there is a chavismo after Chavez and that it is stronger than what the opposition is currently offering.

- Published20 November 2013

- Published11 November 2013

- Published9 September 2024

- Published29 October 2013

- Published4 September 2013

- Published22 May 2013

- Published7 December 2013