Rio's Olympic waters blighted by heavy pollution

- Published

Athletes have complained about the conditions in the water

Mastering the winds and currents of Rio's de Janeiro's stunning Guanabara Bay is a challenge in itself for Olympic hopefuls getting some practise at this week's Brazil Sailing Cup.

With the Sugar Loaf Mountain perched at its entrance, the bay enchanted navigators in centuries past, but today its natural beauty conceals a modern hazard.

The area is heavily polluted and sailors here have to add evading obstacles - everything from TVs, floating bed frames and dead animals - to their skills.

In addition they must never swallow any water.

Brown waves

"I was ill just before Christmas. It could have been from the capsize that we had, or from something I ate," says British sailor Alain Sign at Niteroi's Sao Francisco Beach.

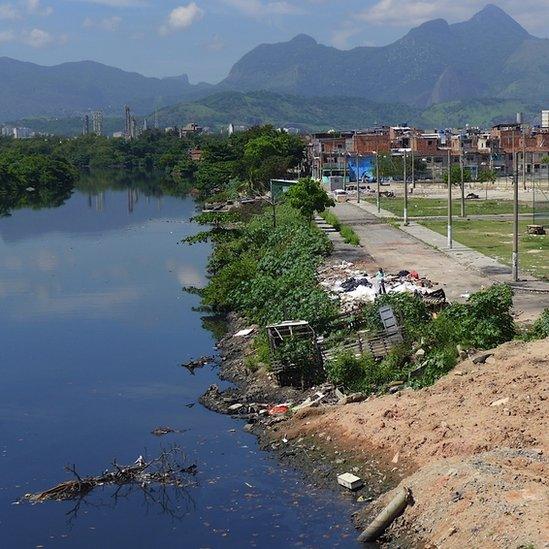

Many of the shanty towns adjoining Guanabara Bay have inadequate sanitation

"You probably wouldn't want to drink the water."

The beach reflects the deep blue sky, but up close breaks into brown waves laden with plastic bags, leaving bits and pieces of rubbish on the sand.

"We've been told to drink Coke afterwards if we swallow any water. We're just trying to not fall ill while we're here."

On top of health concerns, getting rubbish such as a plastic bag stuck in the rudder can be a real setback in a competitive race where speed is crucial.

And running into something big can mean real damage to the boats.

Unsuitable for swimming

The promise to clean up the notoriously filthy Guanabara Bay was part of Rio's Olympic bid.

Biologist Mario Moscatelli accuses the government of opting for short-term solutions to tackle the pollution problem

The government has started to operate 10 'eco-boats' to scoop up rubbish from they bay's waters

Despite poor water quality, fish are still to be found in Rio's Fundao Island

Guanabara Bay has become a repository for all kinds of rubbish

Thirty months from the games, the goal of treating 80% of its sewage now seems extremely optimistic.

According to Rio's Deputy State Secretary of Environment Gelson Serva, only 34% of Rio's sewage is treated - the rest is spilled raw into the waters.

The water quality in the state's beaches is assessed weekly by Rio's Environment Institute (Inea), and most of those across the 148-square mile bay are repeatedly considered unsuitable for swimming.

Botafogo Beach for instance - with the iconic Sugar Loaf as a backdrop - did not get one positive result in 2013 due to faecal pollution levels.

Fifteen cities surround Guanabara Bay. That means over eight million residents, producing over 18,000 litres of sewage per second.

Many live in precarious conditions, with poor housing and often no sanitation or rubbish collection.

The scale of the clean-up operation the authorities must accomplish is huge

Rubbish and sewage flow into the bay through its 55 rivers, once a watershed boasting rich biodiversity. Most of these rivers are now dead and bring sewage and piles of rubbish into the bay.

Biologist Mario Moscatelli is standing on one such heap while showing a mangrove area he has been trying to recover. It is close to Rio's international airport and best known for the foul smell with which it welcomes those arriving in the city.

"I can't understand how the authorities, aware of the date of the Olympics and the size of the problem, are taking so long to implement measures that have already been approved," he says.

An outspoken environmentalist, he says the government opted for short-term solutions.

'Decades of neglect'

And even these measures, like building river treatment units to clean up the waters before they reach the bay, are slow.

It is feared that pollution in the bay could seriously affect Olympic sailing competitions

"Of the seven river treatment units planned, only one has been built so far and there are only 30 months left," he says.

This is one of 12 steps in the government's "Clean Guanabara" plan, announced last year - four years after the Olympic bid.

Gelson Serva says the government needed time to plan the actions and is investing $1bn (£608m) in sanitation projects.

"We are facing a huge challenge, caused by decades of neglect. There are no immediate solutions. We're going step-by-step and the population will feel improvements in the next years."

Mr Serva says the Olympic sailing regattas will be able to take place safely.

'Summer of Sanitation'

Measures are being taken to reduce the amount of solid waste in the bay, like "eco-barriers" installed at the mouth of rivers and "eco-boats" to scoop up rubbish from the water.

The Piscinao de Ramos artificial lake in Rio de Janeiro draws on seawater from Guanabara Bay

But critics say these solutions are stopgap measures.

The NGO My Rio is organising a "Summer of Sanitation", involving a series of protests to put pressure on the government.

They demand the creation of a regulatory agency to control the state's sewage and water company (Cedae) and the implementation of basic sanitation in Rio's shanty towns.

"There's no way the problem will be solved by 2016, but hopefully the attention we are trying to raise will help create change," says campaign co-ordinator Leona Deckelbaum.

She says the level of faecal matter in the bay is 198 times higher than the legal limit established in the United States. "I wouldn't put my little pinky toe in it."

Rio residents are weary of programmes to clean up the bay after the fiasco of a $1.2bn (£740m) investment announced in 1992, during the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development.

Mostly funded by the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) and Japan's International Co-operation Agency, the money was spent, but little changed.

"We have money and we have technology. What we don't have are serious politicians," says biologist Mario Moscatelli.

He is sceptical, but says whatever can be done must be done now.

"After the Olympic Games, you can be sure that all the money and political will are going to vanish."

- Published7 January 2014

- Attribution

- Published25 November 2013

- Attribution

- Published9 September 2013

- Published28 June 2013

- Published28 June 2013

- Published1 August 2013