Cuba asserts American vision without US

- Published

Cuban President Raul Castro (l) hosted dozens of regional leaders in Havana

This week, Cuba was converted into the focal point of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Streets were closed to the public as convoys of smart cars swooped through Havana carrying heads of state and ministers from 33 countries.

They came for the second summit of CELAC, a community formed expressly to exclude the US and Canada.

Hosting the event was something of a political triumph for Cuba's government after decades of US policy aimed at isolating the Communist-run island; it came as the European Union confirmed moves to normalise relations with Havana after a long stand-off.

'Unity amid diversity'

CELAC was conceived in 2011 as a counterbalance to US influence in the region: an alternative to the Washington-based Organization of American States, the OAS.

That is the bloc the US got Cuba excluded from in 1962 for its "incompatible" Marxist-Leninist ideology. By the end of the year, all countries in the CELAC region apart from Mexico had cut ties with Havana.

"It's obviously been a long road back for Cuba, but now it's hosting the whole community of Latin America," says Carlos Alzugaray, a retired Cuban ambassador.

"It's a great success," he believes, of an event that has brought together governments from across the political spectrum for an agenda of talks, dinners and Cuban music.

Cuba's President Raul Castro described the goal as building "unity, amid diversity".

The result was a very broad 16-page declaration which declares the region a "zone of peace", committed to resolving difference through dialogue; other vows include combating inequality in a region with vast natural resources, but more than 11% of the population living in 'abject poverty.'

Legacy of Chavez

Cuba will have been satisfied with the swipes at US policy: a call to end five decades of economic sanctions against the island, and affirmation of the "inalienable right" of every country to chose its own political system.

There was also an expression of solidarity with Argentina's territorial claim to the Falkland Islands, or Las Malvinas as Argentina calls the disputed islands, and criticism of the "colonial status" of Puerto Rico.

Still, with no permanent institutions - and non-binding resolutions - there is some scepticism about what CELAC can really achieve in an already crowded arena.

"CELAC's creation and the chairmanship for Cuba is a legacy of Hugo Chavez's vision of a Latin America without the US,' believes Paul Webster Hare, a former British Ambassador to Cuba now based at Boston University.

Talking shop?

Although Cuba's exclusion from the OAS was annulled in 2009, Havana insists it has no interest in re-joining a group it sees as dominated by Washington.

"Now Chavez is gone, CELAC is unlikely to overtake the more structured and institutional regional organisations in Latin America like UNASUR," Paul Hare argues, referring to the 12-nation South American union.

CELAC is considered to the the brainchild of the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez

He suggests that CELAC has limited scope to evolve beyond a talking shop.

But Carlos Alzugaray argues that these are early days. He sees potential in some CELAC resolutions like the creation of a forum with China.

"Even though there are different outlooks, all the countries accept that the region should speak with one voice where possible. Clearly there will be some issues where that's difficult, but then the same goes for the EU," he points out.

For Cuba, the summit had value for its symbolism alone.

Workers spent weeks sprucing-up Havana for its moment in the spotlight. Long-suffered pot-holes disappeared and kerbstones along key routes gleamed with fresh paint.

And strident messages were pasted to billboards that every presidential convoy would pass: one declared that revolution continues "with no duty to anyone but the people".

A second slammed the US economic embargo as "genocide".

Human rights

Increasingly, Cuba's powerful northern neighbour is looking like the isolated one.

That sense was underlined by the news that the EU looks set to start revising its relationship with the island.

The bloc currently links relations directly to improvements in human rights, based on a Common Position from 1996.

Concern over human rights in the one-party state do remain.

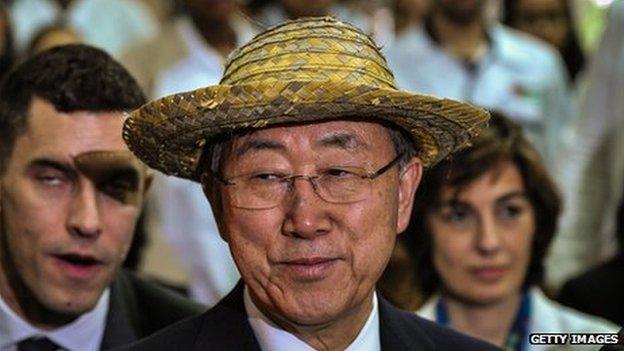

They were underlined by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon who was in Havana for the summit and called on Cuba's government to ratify the international treaties it has signed.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon also attended the CELAC summit in Havana

"I emphasised the importance of [...] enhancing human rights: peaceful assembly and association, and the cases of arbitrary detention that are occurring in Cuba," Mr Ban said of his meetings with Cuban leaders including former President Fidel Castro.

"Diversity includes plurality of views even on political matters and that diversity should be respected," he stressed, in a country that bans all organised opposition and denounces dissidents as 'agents' of enemy powers.

There were complains of increased harassment and short-term detentions in the run-up to the summit as well as criticism that Cuba was even contemplated as CELAC host.

Despite that, the international mood appears to be for engagement and dialogue over isolation - a shift partly prompted by gradual social and economic reforms on the island.

So turnout for CELAC was impressive, luring left and right-wing politicians alike. By the end, all vowed that promoting the regional bloc as an international political player would be a priority.

Despite their differences they agreed that CELAC is now the region's "legitimate representative" and as Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff put it, these days "without Cuba, we are not complete".

- Published27 January 2014

- Published26 January 2014

- Published3 December 2011