Filming under fire - the perils of documenting truth in Brazil

- Published

- comments

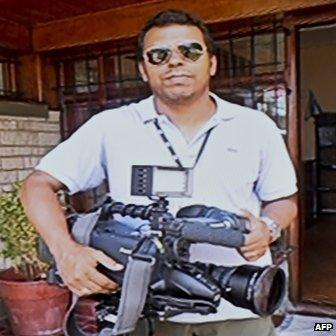

Santiago Andrade worked for the Brazilian "Bandeirantes" network

Today I went to the funeral of a man I didn't know.

But everything I've heard and read about Santiago Andrade in the last few days makes me wish I had known him and had been able to spend more time with him.

As it was, the brief few minutes our paths crossed in a Rio de Janeiro plaza last week were chaotic, messy and ultimately futile. For perhaps another hour and a half, I remained with the 49-year-old father of four at a city centre hospital as doctors fought to save him.

Santiago Andrade never left the hospital alive.

It has been exactly a week since the photojournalist for the Brazilian "Bandeirantes" television network collapsed to the floor as a flare or firework-type device exploded just behind his head as he was covering the latest in a series of anti-government protests in Rio.

Less than four seconds later, my BBC colleague, Keith "Chuck" Tayman and I were at his side.

Before arriving in Brazil some five months ago, I had spent the last three years based in the Middle East covering, among other events, the often-traumatic Arab uprisings. In Egypt, Gaza and Libya I witnessed some shocking and emotionally distressing scenes and saw, far too frequently, the terrible consequences of conflict.

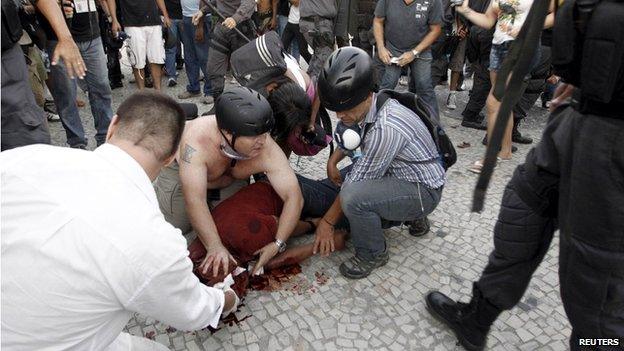

So when I knelt down beside Santiago's big, prone body, I wasn't in any way frozen or unsure what to do, even though his injuries were appalling. The explosion had left a sizeable wound in his head from which blood was already starting to pour.

All BBC staff who work in conflict zones are given regular "hostile environment" training - the most invaluable part of which is without doubt a comprehensive first aid element. Having also previously worked as a mountain/expedition guide, it is training I have used on many occasions.

Screaming

In the absence of a first-aid kit or heavy-duty bandages to hand, Chuck instinctively tore off his t-shirt and pressed it hard on Santiago's head wound to stem the flow of blood. And, although unconscious, Santiago was breathing quite heavily. Amid the chaos, we did our best to stabilise him.

A protester has now been on arrested on suspicion of launching the object that killed Mr Andrade

I have seen many victims of violence left lying on their backs, police or bystanders unwilling or unable to help as critical moments slip by.

By the time professional medical help arrives, it is often too late; the victim may have died through blood loss, heart failure or simply because basic checks to monitor their breathing weren't made.

Santiago's injuries were so serious we knew we had to get him to hospital, but some of the police were being obstructive - perhaps not realising the gravity of the situation - and many protesters were berating and screaming at the security forces, blaming them for the attack. It has since been shown that, almost without doubt, the flare was thrown by one of two protesters later identified in television footage.

While treating Santiago on the floor, we also had to "take control" of the situation. Repeatedly impressing on police the urgency of the moment, we carefully carried the 13-stone (82kg; 182lb), limp body into the back of a police car and sped off to a nearby hospital.

It seemed like an age but from the moment I saw Santiago drop his camera and fall to the floor, to that screeching journey to hospital against the flow of traffic down Rio's main avenue, took just six minutes.

Chuck and I had hoped it would be enough time to help save Santiago Andrade's life.

Moving tribute

Knowing it would probably be the last time she would see her father alive, Vanessa Andrade also spent some time with him this week at his hospital bedside.

Writing from the heart but with the clear head of someone who wants to say the right things and remember precious moments, the 29-year-old later wrote on her Facebook page about her dad and her last "conversation" with him.

Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff said Mr Andrade's death had caused "revulsion and was saddening"

"He taught me many things, that people from a humble background must work twice as hard to make it in life," said Vanessa, who has continued her father's vocation as a media professional.

In an incredibly moving tribute, she continued, "Tonight I said goodbye, just me and him. With my head on his shoulder we talked about many things. I asked forgiveness for my shortcomings …. I know he's okay. Of course he is. And I am the continuation of his life."

In an often brutal and polarised society, many of Santiago's colleagues described him as a big but gentle man who hated violence and did all he could to avoid confrontation.

At his well-attended wake and funeral today in a Rio suburb, colleagues from Band News and dozens of other Brazilian journalists remembered a man who had worked to minimise the threats posed to media professionals.

Threat of violence

Here in Latin America, where journalists are often in danger of becoming targets, rather than being allowed to operate unhindered as independent observers, the concept of legal rights for media professionals is not entrenched.

According to recently released figures more media workers were killed in Brazil than anywhere else in the region, even Mexico where reporters are frequently intimidated and have been forced to work anonymously.

"In Brazil, journalists work under a widespread threat of violence and major police crackdowns," said the 2014 World Press Freedom Index, external, which was released earlier this week.

It's a learning curve for journalists too. Remaining dispassionate observers of complicated and traumatic events is the best way to make sure the whole picture is seen.

Sadly, even in the days since Santiago died, some parts of the Brazilian media are in danger of being unwittingly used and manipulated by political forces to demonise the whole protest movement, not just the few mindless individuals who are bent on violence and confrontation.

These are dangerous but also fascinating days to be a journalist in Brazil, things I would dearly have loved to have talked about with a man committed to his job and his family.

- Published9 February 2014

- Published7 February 2014