Man and myth: Joaquin 'Shorty' Guzman

- Published

This image from 1993 shows a jailed Guzman, but he escaped in 2001 and eluded the authorities for 13 years

"From his feet to his head, he is short, But from his head up to the sky, I'd say, He's the biggest of the big, Who could possibly doubt it?"

The above words come from a narco-corrido, a musical homage to Mexico's wealthiest drug lord Joaquin 'El Chapo' or 'Shorty' Guzman.

Sung at local fiestas in his birthplace of Badiraguato in the western state of Sinaloa, the lyrics sum up the strange mixture of admiration, fear and respect which many in that mountainous region have for the world's most wanted drug trafficker.

The stories about him are legion: his diminutive stature, his wealth, his women.

Worth an estimated $1bn (£630m), he featured annually Forbes rich list, external and was a fugitive from justice for more than 10 years.

Until this week, when his long flight from the authorities finally came to an end when he was arrested in his home state of Sinaloa.

In a country which has produced some of the most notorious drug lords, Joaquin Guzman Loera stood out.

"I think 'El Chapo' has become the most iconic drug trafficker of modern times," says Ioan Grillo, author of El Narco, an in-depth examination of Mexico's drug cartels.

"Even more so than the biggest drug trafficker of the 1980s, Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo, who he once worked under. El Chapo went beyond that in the last six or seven years to become the most recognisable drug trafficker in the world and the most high profile warlord in the present conflict."

So what made this uneducated cattle rancher's son get so good at controlling the illicit flow of cocaine, heroin and marijuana into the United States?

The respected Mexican magazine Proceso recently described Guzman as "the capo who took most advantage of the globalised dynamic of drug trafficking".

Certainly, when first starting out in the drug-smuggling business in the late 1970s, he rose quickly through the ranks of the Guadalajara Cartel by reportedly pushing his bosses to let him handle greater volumes.

He has also been credited by several biographers with finding innovative ways to move the drugs north.

Cult figure

Internationally, too, he has always thought big.

Today, his sphere of influence is vast. His Sinaloa Cartel has tentacles in Europe, Asia and across Latin America.

But, says Ioan Grillo, it was not just a canny understanding of the processes of globalisation that made Guzman unique as a drug lord.

"Drug trafficking has always been a collective endeavour. It's not about just one guy smuggling all the drugs," he said.

"There are hundreds of individuals, thousands even, in the Sinaloa Cartel who have been very adept at tapping into the US drug market, bringing down the price of cocaine from the Colombians, moving into crystal meth (methamphetamine) to bolster the heroin and marijuana trade."

Mr Grillo argues that what set El Chapo apart was his pragmatism.

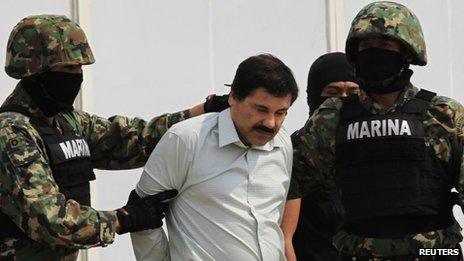

Hours after his arrest, Guzman was paraded before the world's media at a military compound in Mexico City and taken straight to jail

"His ability to rise to the top through the selective use of violence, to survive the extreme violence against him and all the while to create this huge mythology around him... it all made him something of a cult figure so that he is now recognised right across Latin America."

So much so, that drug groups in other countries have sought to tie themselves to his name and ally their organisations with his cartel, in the knowledge that his surnames, Guzman Loera, carry great weight in the criminal underworld.

He also commanded great loyalty, both among his foot-soldiers and the local communities in states such as Sinaloa, Durango and Chihuahua.

But Mr Grillo argues that the stories about Guzman can be misleading.

"Sometimes the myth takes over, and in fact he wasn't as all-powerful as he's been portrayed. For example he was never able to take (the state of) Tamaulipas in the north-east of Mexico and faced ongoing battles across the country from his rivals."

Of course, there is an important political dimension to Guzman's demise.

It is a huge boost for the administration of President Enrique Pena Nieto. Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman has evaded arrest since he escaped from prison in 2001.

The removal of a figure like Guzman plays well both at home and in Washington.

However, many fear this may be the start of something much more bloody in Mexico, at least in the short term.

"Taking 'El Chapo' down will be extremely destabilising," says Mr Grillo.

"The pattern has been very clearly that when the big godfathers have been taken out, it's always created violence. Their lieutenants fight among themselves for control."

The signs for Mexico are ominous.

"This could be an earthquake in the drug smuggling industry in the areas of north-west Mexico and the Pacific coast. We could really see an eruption of violence with 'El Chapo' now out of the game," says Mr Grillo.

- Published27 September 2011