Trouble in paradise for Chile's Easter Island

- Published

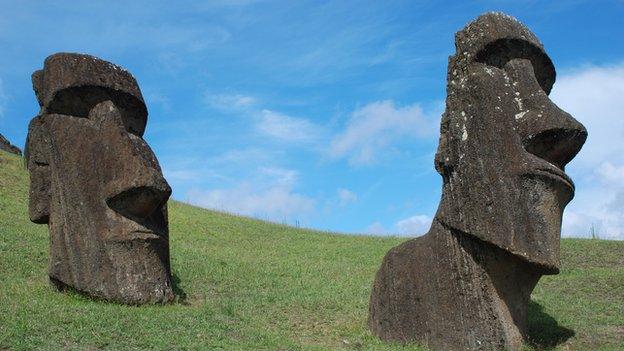

The Easter Island of popular imagination is green, lush, wild and famous for its monumental statues

A few years ago, Chile's leading newspaper El Mercurio published a big article on the 10 biggest problems facing Easter Island, the remote Chilean outpost in the South Pacific.

They included dengue fever, the lack of a decent hospital, a steady accumulation of garbage, over-fishing, the arrival of thousands of tourists each year and damage to the moai, the giant stone statues that have made the island famous across the world.

Easter Island, it seemed, was far from the South Sea paradise of popular imagination.

Fast forward to 2014 and the island is tackling some of these issues. It has a new hospital and a recycling plant.

But even so, it is a problematic place.

Middle of nowhere

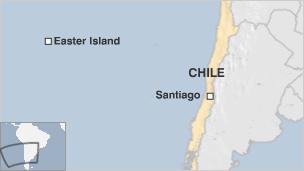

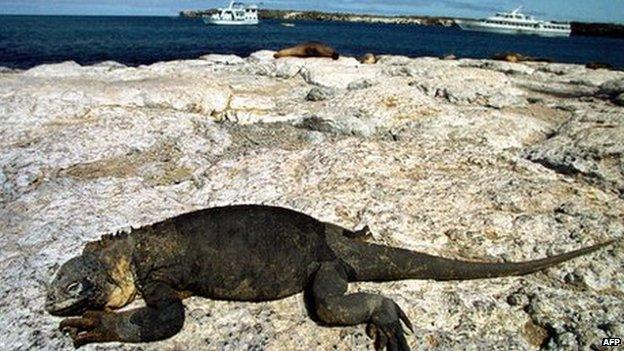

Like the Galapagos, the Maldives and scores of other tiny islands across the world, it faces tough questions that go to the heart of 21st Century life.

How do you develop a sustainable tourist industry when, each year, more people want to visit? Do you limit visitor numbers? How do you ensure local people do not feel crowded out? How do you provide basic services in such a remote outpost?

How, in short, do you manage an island like this?

Until you visit Easter Island, it is difficult to grasp just how remote it is. By some measures, it is the most isolated permanently inhabited place on earth.

The next-door neighbours live on Pitcairn, over 2,000km (1,250 miles) to the west. The South American mainland is 3,600km away - a five-hour flight.

And Easter Island is tiny - just 25km from one end to the other. Just under twice the size of Manhattan and less than half the size of Britain's Isle of Wight.

It has a population of about 6,000 and yet receives 80,000 tourists a year, bringing in cash but putting a tremendous strain on services.

It produces 20 tonnes of rubbish a day. The recycling plant, opened in 2011, processes 40,000 plastic bottles a month.

But much of the island's garbage cannot be recycled.

"We put it into landfills and they only thing we can do is flatten it," says Easter Island Mayor Pedro Edmunds.

.jpg)

Mayor Pedro Edmunds says dispensing with the island's rubbish is a major problem

"We can't burn it and we have no more land to dump it in. It attracts rats, mosquitoes and stray dogs."

In recent years, the islanders have sent scrap metal and cardboard to the Chilean mainland for recycling but it is prohibitively expensive.

Because of the risk of dengue, it has to be fumigated before arrival at Chilean ports.

"There are companies in Chile which buy cardboard, aluminium and plastic but the cost of shipping is so high that you end up paying them rather than them paying you," Mr Edmunds says.

The long-term plan is to incinerate waste to generate electricity, but that is still some years off.

With tens of thousands of people visiting the island every year, rubbish and its disposal has become a hot topic

Sending waste for recycling to the mainland is very costly

Cans are flattened so they take up less space on the journey to the mainland

The Chilean government opened a new hospital on the island in 2012 but the mayor says it is poorly financed and has not done much to improve healthcare.

"It's a spectacular building, like an eight-star hotel, but the service? It's not just bad, it's atrocious," he says. "They've put a tuxedo and a bow-tie on a pig, but it's still a pig."

Leo Pakarati, director of the island's online newspaper, El Correo del Moai, says doctors and dentists will not come to the island to work in the public hospital because they can earn more in the private sector elsewhere.

"You have to wait a couple of months for a hospital appointment," he says.

Limited space

As Easter Island's tourist industry has taken off, Chileans have moved from the mainland to live here, opening hotels, bars and restaurants.

They now outnumber the Rapa Nui - the original Easter Islanders of Polynesian descent.

That has created tensions. Mr Pakarati describes the islanders as "victims of indiscriminate immigration" from Chile which, culturally, has little in common with the island.

"There isn't enough space for everyone, enough drinking water, enough fuel," he says. "This is about sustainability and quality of life."

Like other Rapa Nui, Mr Pakarati says the number of immigrant residents should be restricted and the locals should have more say in how the island is run.

"Our conflict is not with the Chileans, it's with the inefficient Chilean state," he says. "The Rapa Nui are one big tribe, and our territory should belong to us."

Unforgettable sight

Mr Pakarati cites the Galapagos Islands as an example that Easter Island might follow.

There, foreign tourists pay an entry tax of $100 (£60) to visit protected areas, and the Ecuadorean government has made some efforts to curb population growth and manage tourist numbers.

Tourists arriving on the Galapagos islands have to pay a tax

"We currently receive around 80,000 tourists a year," Mr Pakarati says. "Studies suggest that if that figure rises above 100,000 the consequences could be disastrous."

Overfishing is also a problem. The island's tuna and lobster are highly prized in the restaurants of Santiago.

Mr Edmunds blames foreign fishing fleets for plundering the island's waters, describing the southern ocean as "full of pirates".

Easter Island is a stunning place. The moai, standing on their stone plinths and gazing over the rolling, green landscape, are an unforgettable sight.

But it is clear this is an island with issues.

If unaddressed, they could eventually threaten the future of one of the most unique places on the planet.

The moai are a huge draw for tourists

- Published7 June 2013

- Published7 August 2012

- Published7 February 2011