Gabriel Garcia Marquez: Guide to surreal and real Latin America

- Published

Colombian newspapers have declared Gabriel Garcia Marquez "immortal"

In the mid-1980s as a young undergraduate student of Latin American politics, to me Gabriel Garcia Marquez was as much a political historian as he was a writer of fantastical novels.

In the days since his death at the age of 87 in his adopted home of Mexico City, many have written about the brilliance of masterpieces including One Hundred Years of Solitude, Autumn of the Patriarch, and Love in the Time of Cholera.

Those literary classics persuaded many that Garcia Marquez was quite simply one of the greatest authors of the 20th Century.

But like his contemporaries Mario Vargas Llosa, Pablo Neruda, Carlos Fuentes, Victor Jara, Isabel Allende and many others, the moustachioed Colombian found himself thrust into the politics of a volatile, unstable and increasingly violent region.

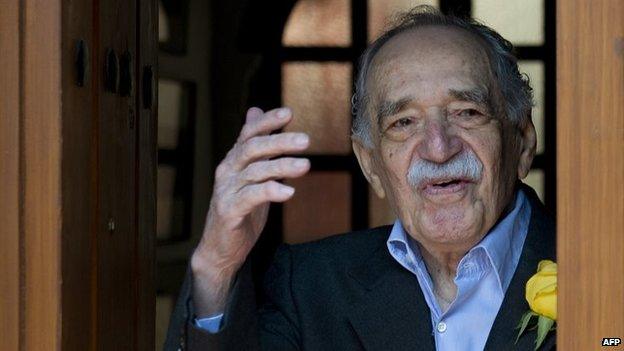

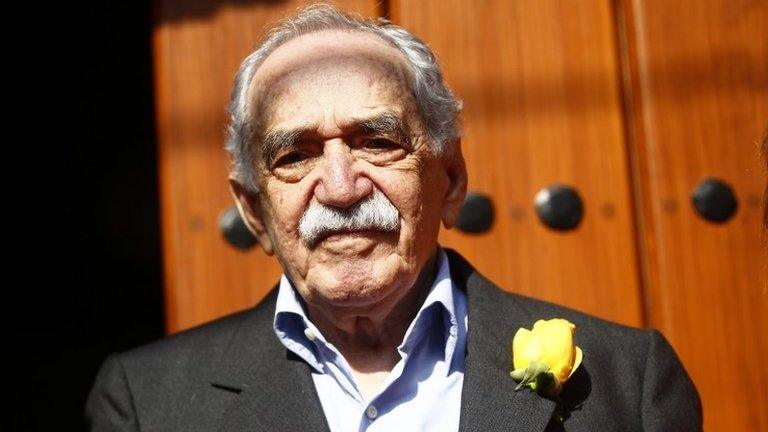

Garcia Marquez died last week in Mexico City aged 87

Latin American artists, songwriters and authors became important fixtures in the changing political landscape in the 1960s and 70s.

Some, like Chile's Jara, were tortured and murdered for their bravery and outspokenness. Others, including Garcia Marquez, found themselves strangers in their own countries and wandered the globe perhaps searching for an ultimately unattainable utopia.

'No firearm'

By the time of his death, and despite failing health that minimised his public appearances in recent years, Gabriel Garcia Marquez was arguably Colombia's most celebrated and sought-after son.

Old political divides were long forgotten and the grief at his passing has left all Colombians bereft.

It was a role of prominence and political influence that, after his humble beginnings in newspaper journalism and short-story telling, the author affectionately referred to as Gabo neither sought nor initially relished.

"I don't think literature should be used as a firearm. But, even against your own will, your ideological positions are inevitably reflected in your writing and they influence readers," he said in a 1988 interview with the New York Times.

Residents of Garcia Marquez's hometown of Aracataca held vigils after news of his death became public

"I think my books have had political impact in Latin America because they help to create a Latin American identity; they help Latin Americans to become more aware of their culture," he added.

Like many Latin American artists, Garcia Marquez was a fervent anti-imperialist.

He was highly critical and deeply suspicious of North American political and economic meddling in the region - a region that US leaders at the time referred to as "America's backyard" and, moreover, where they felt they had a legal and God-given right (through the Monroe Doctrine et al) to interfere.

Garcia Marquez was equally damning of those Latin American leaders and classes who grew fat and wealthy off the back of their countrymen and the land which belonged to everyone and no-one.

Much has been made of his preferred (but not his only) writing style, magical realism.

Surreal reality

Gabo was neither the first nor the last to combine surreal and real physical worlds into one perfect, rounded work of art but he was without question its best exponent.

Perhaps for me, as a news journalist, I clung to those real worlds and those references that I recognised.

For while the crazy, fantastical, mythical characters may have belonged to the fantasies and stories the young Gabriel heard from his grandmother, the frontier towns, the jungles and corrupt fiefdoms were pure contemporary Latin America.

Garcia Marquez drew inspiration from his childhood in the Colombian town of Aracataca

The town was the model for Macondo in One Hundred Years of Solitude

The home in which Garcia Marquez was born has been turned into a museum

A joker with a subtle sense of humour in his writing, Garcia Marquez sometimes seemed taken aback by how seriously his novels were appreciated.

As he himself said, there was not a single line from his work that did not have a basis in reality. But he was far too modest.

The characters and the scenarios he wrote about portrayed the Latin American condition in all its beauty and ugliness. Dictators, lovers, peasants, oligarchs, the wild interior and the rugged coasts were all introduced to us by Gabo and, most importantly, helped Latin Americans understand their own culture and continent.

Political animal

Garcia Marquez and a plethora of other gifted Latin writers exposed the savagery and wretchedness of rural poverty in their novels. We also learned to recognise the murderous brutality of military strongmen and the futility of civil war through his words.

He was also an unashamedly political animal, but only to a point.

After having initially left his native Colombia over concerns that the army was investigating his alleged association with leftist guerrilla groups, he was later persuaded to come back to try to broker peace talks between the guerrillas and the government in Bogota.

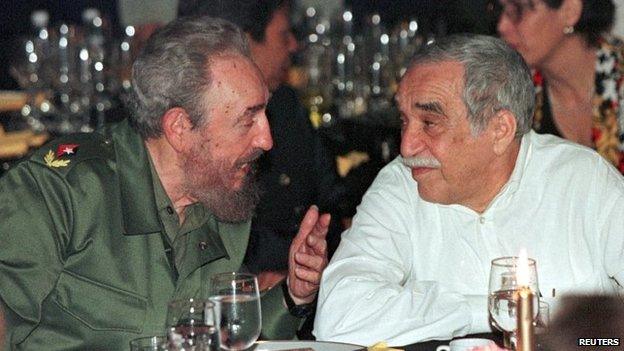

Like other Latin American writers with predominantly leftist leanings, Garcia Marquez was criticised for continuing to support the regime of Fidel Castro in Cuba, even when it was arresting and jailing its own literary dissidents.

Garcia Marquez was criticised by many for his friendship with Cuban leader Fidel Castro

Gabo maintained that his friendship with Castro was almost purely based on the Cuban leader's appreciation for literature and that their relationship was not political.

Accused of hypocrisy, it was cited as one reason behind one of the most celebrated feuds in Latin American society when Gabo and the Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa fell out and even had a brief street fight in 1976.

Wisely, Garcia Marquez knew the limitations of his political ambitions. Despite considerable pressure, he never sought political office - unlike Vargas Llosa, whose bid for the Peruvian presidency failed, leaving him disillusioned and in the eyes of some, partially discredited.

Dreamer

Perhaps as Dickens had been to the English language, Garcia Marquez was ultimately a chronicler whose fantastic stories were nonetheless firmly rooted in the truth of his own experiences or those of his family.

Indeed, he always thought of himself as a journalist.

Occasionally, as in the wonderfully gripping News of a Kidnapping, he used very real events to describe the details and horrors of Colombia's descent into turmoil in the 1980s as ruthless drugs barons battled with corrupt and compromised politicians for control of the country.

Garcia Marquez was also a dreamer whose writings reflected his love for the innocence and passion of life, despite its shortcomings and inevitable disappointments.

To him, utopia was always theoretically attainable, were it not for the frailties of men.

In No One Writes to the Colonel, even though the impoverished central character is betrayed by all and sundry, he still manages to utter the line: "Life is the best thing that has ever been invented."

Adios, maestro.

- Published19 April 2014

- Published17 April 2014

- Published17 April 2014