Chile's energy dilemma after ditching megaproject

- Published

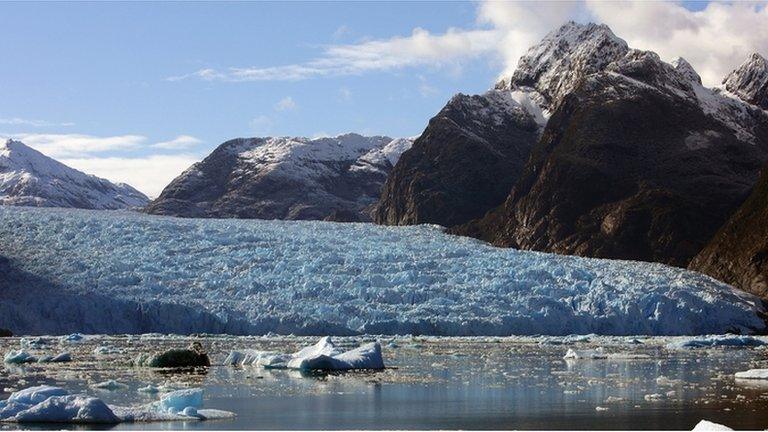

Patagonia, in Chile's far south, is renowned for its wild beauty

Following the Chilean government's decision to scrap what would have been the biggest energy project in the country's history, the BBC's Gideon Long asks what Chile will now do for energy instead

It is the most energy-poor country in South America, producing virtually no oil and gas of its own.

It used to import gas from neighbouring Argentina, but the Argentines turned off the taps to feed their own domestic demand.

In theory, Chile could buy gas from Bolivia, but the Bolivians refuse to sell it to Chile due to a long-standing border dispute.

Until recently, Chile considered nuclear power as an option, but the Fukushima disaster of 2011 put paid to that. Chile is every bit as prone to earthquakes and tsunamis as Japan.

The HidroAysen project would have gone a long way to addressing this chronic energy shortage. With an installed capacity of 2,750 megawatts, it would have provided enough energy to cover around 15-20% of the country's needs.

But the project was controversial from the outset.

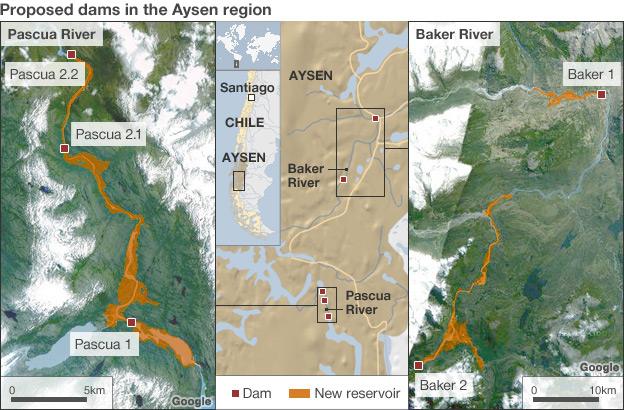

It would have involved the construction of five dams on the fast-flowing Baker and Pascua rivers and the flooding of 5,900 hectares of land.

Although Endesa and Colbun pointed out that that represents just 0.05% of Aysen's surface area, environmentalists were outraged that the companies could even consider spoiling an area of such rugged natural beauty.

Environmentalists have opposed the project from the start

"Compared to many hydro-electric schemes in the world, HidroAysen would have actually been very efficient," said Hugh Rudnick, an expert in energy at the Catholic University in Santiago.

"The area to be flooded was very small for the amount of electricity it would have generated.

"But it's been defeated by a well-organised campaign by NGOs who've managed to convince the country that it would mean that the whole of Aysen would be flooded."

The project would have also required the construction of one of the longest transmission lines in the world to bring electricity from sparsely populated Patagonia to the centre and north of the country where it is needed most.

Faith in renewables

The government says the alternative to HidroAysen lies in the measures it announced in its energy agenda last month.

There were divisions among lawmakers about the project

They include the construction of a Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) terminal in the south of the country, enabling Chile to import gas from overseas.

The country has already built two such terminals in recent years, one in the north, to feed the vast copper mines in the Atacama desert, and one in the centre to supply the industrial and residential heartland around the capital, Santiago.

The terminals have helped Chile break its dependency on its Latin American neighbours, but LNG remains a relatively expensive source of energy.

The government also sees scope for efficiency savings, which will help curb the demand for energy.

For example, it says solar panels should be installed on all new public housing.

In its energy agenda, it announced a series of measures that it said would cut energy consumption by 20% from the level that it would otherwise reach by 2025.

"They're talking about saving 2,000 megawatts simply through savings and by being more efficient," said Raul Sohr, author of three recent books about the energy sector in Chile.

"That alone is about 80% of the power that HidroAysen would have provided."

The other great hope for Chile lies in renewable energy. The country is poor in fossil fuels, but potentially rich in the energies of the future.

Natural potential

The sun that beats down on the Atacama desert could be used to produce plentiful solar power.

The Atacama is the driest desert in the world and could provide plenty of solar power for Chile

Chile is home to hundreds of volcanoes that could provide geothermal energy.

And the country boasts one of the longest coastlines in the world, making it an ideal spot for tidal and wave power.

The state has set a target of producing 20% of the country's electricity from non-conventional renewable sources by 2025. At the moment, such sources account for about 6%.

Mr Sohr describes the target as conservative and says that by 2050, non-renewables could provide around 70% of Chile's energy needs.

The problem is in the short to medium term. Currently, Chile imports 60% of its primary energy and relies heavily on coal-fired power stations.

The decision to scrap HidroAysen makes the search for alternatives to coal all the more imperative.

- Published19 March 2014

- Published4 April 2012

- Published31 May 2012