In pictures: Illegal logging in Peru

- Published

Almost two-thirds of Peru's territory is covered by the dense jungle of the Amazon rainforest.

Logging is a lucrative industry and timber extracted from the rainforest a key export. But despite the government's attempts to promote sustainable practices, illegal logging is continuing apace.

A 2012 World Bank report, external estimates that 80% of Peruvian timber export stems from illegal logging.

The Peruvian government requires loggers to show that the timber came from areas where logging is allowed. In theory, they are required to show that the wood they have cut comes from an area where a logging concession was granted and to document how much was cut.

But the remoteness of the areas where illegal loggers operate and the fact that the authorities rarely patrol these areas mean the potential for illegal logging is vast.

Photojournalist Fellipe Abreu travelled to north-eastern Peru and spent time with the illegal loggers. They told him how they circumvented the rules.

The Javari river marks the border between Peru and Brazil. Illegal loggers use the river like a highway to float logs they have illegal extracted from the forest to the tri-border area to the north, where Peru, Brazil and Colombia meet.

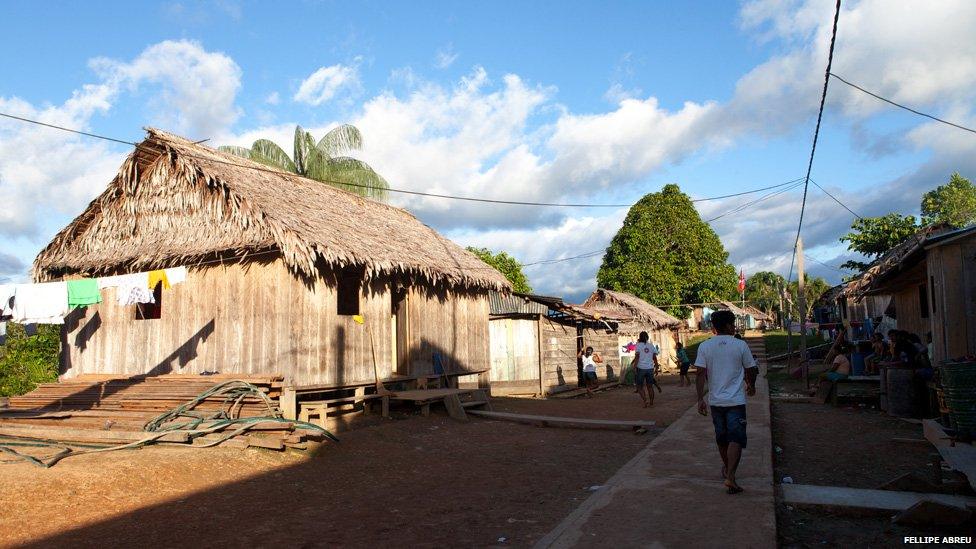

The high prices which timber can fetch on the international markets has fuelled a logging boom. Villages such as Nueva Esperanza, meaning New Hope, have sprung from this boom.

Almost all of its 300 residents make a living either directly or indirectly from logging. Most are loggers themselves, or the families of loggers, others are merchants who rely on loggers to purchase goods from them.

Paulo (not his real name, in camouflage top), his brother-in-law, nephew and son venture into the forest to cut down trees.

Paulo is employed by the mayor's office in Atalaia do Norte, in Brazil. He also teaches at a school in Palmeiras do Javari, an army base on the Brazilian side of the border, but he sometimes engages in logging to boost his income.

The boundaries between what is legal and illegal are not always clear cut in this area, he explains.

He has come to the Peruvian side of the forest for a few days hunting and to cut down some cedars - neither of which is allowed under the law.

It is not the first time Paulo and his brother-in-law have come to hunt and cut down trees in Fray Pedro, an indigenous reserve inhabited by the Matses community near the Soledad river in Peru.

According to Paulo, the way to go about it is to come to an arrangement with the local indigenous leader.

He explains that in he past he has cut down 30 cedars in exchange for offering the local leader a day's work, but he adds, other forms of payment are also accepted.

Illegal loggers have built small camps deep inside the jungle, a base from which they can go about their daily business.

This camp is two hours by boat from the Brazilian army base of Estirao do Equador. The loggers have built their huts on the shores of the Esperanza river, on the Peruvian side of the border.

Facilities are basic, leaves are used to thatch roofs for shelter and there is a communal kitchen where the men eat a hearty breakfast before a long day's logging.

In the evenings, they play cards to pass the time.

The camp leader says police from the nearest post came to see them when they first set up their huts.

He recalls how they came to an agreement with the officers to pay them 1,000 soles ($350; £210) at the end of the season for the police to turn a blind eye to their activities.

"That's how it works here," he explains.

Once felled, the logs are cut into four chunks, each approximately four metres (13 ft) in length.

A team of six men rolls the log to the nearest stream. One uses a stick for leverage, while the other five push.

They leave the logs in a dry riverbed. When the next heavy rain falls, the logs float and are collected in a bend for transport downriver.

The loggers wait until they have amassed hundreds of logs before making the journey.

When the water levels are high enough and a sufficient number of logs has been felled, a foreman gathers all the logs and ties them together into a big floating raft.

He pays off the local loggers and takes the wood downstream to the Islandia, a Peruvian town in the border area with Brazil and Colombia.

.

In Islandia, sawmills buy the wood off the foreman and process it further.

The illegal loggers and their foremen have found ingenious ways of circumventing the rules and still providing the necessary paperwork required by the buyers.

Some will have bought the required licences off other loggers and altered the documents so as to suggest the wood came from an area where a logging licence was granted.

Others, who have licences for a certain area of the forest, will take wood from outside that area and pretend it comes from the licensed plot.

Often, the wood will be cut down in neighbouring Brazil and floated across the river to Peru to hide its provenance.

It is a practice known as "wood laundering" among the loggers.

By the time it reaches Islandia, the wood - much of it illegally felled - will appear legal and be ready for export to the United States and countries in Europe.