Brazil in narrow presidential race as Silva captures imagination

- Published

Brazil is the world's seventh largest economy, but millions still live in poverty

Brazil is a contradictory, complex country.

It boasts the world's seventh largest economy but Brazilian society is still deeply divided and unequal.

Racism and corruption are still rife yet a mixed-race woman, born into almost absolute poverty in the jungle interior, could soon be elected to lead this country of 200 million people.

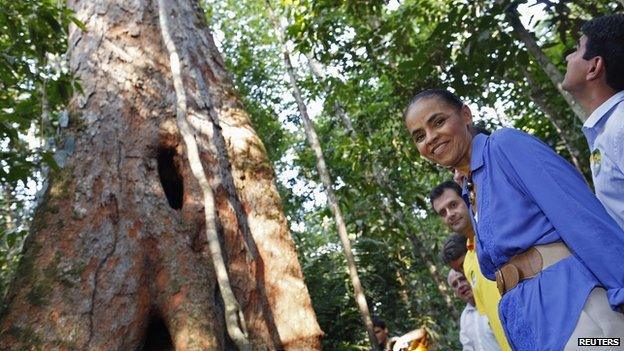

Marina Silva is certainly an enigma.

The slight, almost frail, former environmental campaigner is adored by the foreign media and by those who relish the prospect of a genuinely "green" president in Brazil.

Her detractors say she has flitted like a butterfly from cause to cause, helping to found then abandoning political movements when she became frustrated or didn't get her way.

Silva is known for her environmental campaigners, and her origins in the Amazonian rainforest

More damaging, perhaps, is the perception that she is an idealist - a "dreamer" who talks glibly about "a new way" for Brazil without providing detailed policies or putting flesh on the bone.

To try to find the "real" Marina we went back to the beginning, to a time and a place far removed from modern Brazil.

The Amazon state of Acre is proof of how big and complex this country really is.

Until just over 100 years ago this was actually part of Bolivia but thanks in part to occupation of the land by Brazilian rubber tappers, Acre was eventually absorbed into Brazil.

Until the early 1900s Acre was part of Bolivia, but was inhabited by many Brazilians

This is where Marina Silva grew up and where she forged the political ideals that still, to an extent, define her today.

Her parents were both "seringueiros" or rubber tappers, almost the lowest rung of the ladder in a tough and traditional rural society.

If there was no food on the table you went hungry and everyone, no matter if they weren't even yet in their teens, was put to work.

In an unashamedly emotional television advert for the forthcoming elections, Marina Silva recounts a story to her silenced audience about watching her parents go without food, just so their children could eat.

Acre is also known as "The Rubber Tree State" - the trees are an important part of the rural economy

It's a real tearjerker and, on this level at least, it's easy to understand why so many people are so attracted to Marina's bandwagon.

Remember, she only assumed the candidature of the Brazilian Socialist Party when her running mate, Eduardo Campos, was killed in a plane crash.

She worked alongside Chico Mendes, the famous environmentalist and campaigner who was assassinated in 1988 for defending the rights of Brazil's rural workers in the face of overwhelming political and business opposition.

.jpg)

Sebastiao da Silva works in the rubber tree groves - where Marina Silva began her earlier years

Deep in the "mata" - the jungle - after a bumpy ride through forest tracks, more by luck than judgment, we came across Sebastiao da Silva, a small-scale farmer who still supplements his income by tapping trees for sap.

Sebastiao takes me even further into the dense green canopy. There's an abundance of butterflies and an orchestra of bird noise as he sets about gouging an angular line in the bark of a tree.

He places a small plastic cup to collect the white sap and then moves on to another tree. Harvesting latex is slow, physical work. Marina Silva was doing this at the age of 10.

Tapping rubber trees - hard work for a 10-year-old.

"If she becomes president, it'll be tough doing both things - protecting what we have here in the jungle and also promoting the country's development," says Sebastiao, who remembers Marina the young activist.

Wiping sweat from his brow and bugs from his eyes, he adds, "but there's no doubt she can do it because she knows exactly what we need here in the interior."

While few doubt Marina Silva's knowledge of, and commitment to, Brazil's rural heritage, her political opponents seriously question her ability to govern this continent-sized nation.

Three and a half hours flying time from Rio Branco, we land in the capital, Brasilia. The whole point of this "new" city, inspired by the stunning architecture of Oscar Niemeyer, was to unite the vast country in the middle - not north, nor south.

Brasilia's presidential palace was designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer

Holding court here, for the last fours years, has been President Dilma Rousseff. Until the untimely accident that killed Eduardo Campos last month she had a comfortable lead in the polls.

Like Silva, Dilma Rousseff is not part of Brazil's traditional political or landed elite. A student activist who was imprisoned and tortured by the military government in the 1970s she, too, has earned her spurs.

The two women were once ministerial colleagues under the first Workers' Party (PT) government of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and this election has been interpreted by some as a battle for his legacy.

Ms Rousseff is Lula's chosen successor and she claims credit for continuing his widespread social reform programmes that have elevated tens of millions of Brazilians out of poverty.

But she has been unable to replicate the decade of extraordinary economic growth that helped to pay for those social reforms. The economy is stagnant and, according to some interpretations, is even in recession.

Ms Rousseff shows few signs of listening to the concerns of business people and investors who want her to deregulate Brazil's highly protectionist economy - for the president, as long as unemployment and inflation remain relatively low, she's pretty happy.

Rousseff had been enjoying a lead in the polls, but then Marina Silva entered the race and all bets were off

The opinion polls are up and down. Since Marina Silva entered the race, the new Socialist Party candidate maintained an almost constant but narrow lead over the incumbent president.

But it is Ms Rousseff who enjoys more paid-for airtime and has by far the most effective party structure. It's simply too close to call.

David Fleischer, professor of political science at Brasilia University has watched the "wave" of initial support for Silva, from undecided and independents turn into a "tsunami".

He adds, "Dilma has been trying to get things back on track by spreading fear about Marina's alleged naivety and unworkable programme. She's also an incumbent and she has the power of the state at her disposal."

The presence of other candidates in the first round, including the more business friendly Aecio Neves, means a run-off vote at the end of October is almost inevitable.

But there's a long way to go between now and the end of October.

- Published20 August 2014

- Published4 June 2014

- Published27 August 2014