Jose Mujica: Uruguay's rebel turned president comes to term's end

- Published

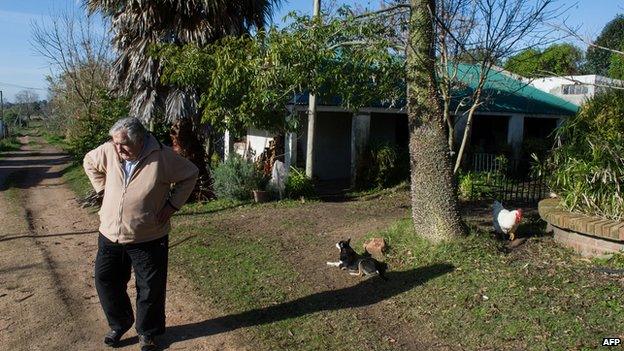

Jose Mujica has continued to live on his little farmhouse rather than in the presidential palace

Voters in Uruguay elect a new president on Sunday and whoever they choose will have a difficult act to follow. Barred from running for a second consecutive term by the constitution, the widely popular incumbent, Jose Mujica, will have to hand over the reins of power. Jonathan Gilbert looks back at his life and what he will be remembered for both at home and abroad.

Jose Mujica's life at times reads more like a film script than a presidential biography.

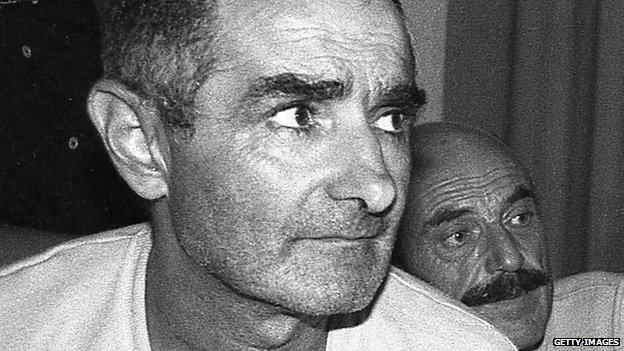

During his time with the armed left-wing guerrilla group Tupamaros in the 1960s and 70s, he survived a shoot-out with police in which he was hit by six bullets.

Captured four times by the authorities, he managed to escape twice, both times through tunnels dug first by rebels on the inside, and a second time, by his comrades on the outside.

Recaptured, he withstood years of inhumane treatment in military jails, becoming emaciated and suffering great psychological trauma.

But his nom de guerre from that era also reveals a softer side. His fellow rebels called him Florero (florist) for his passion for growing flowers.

Going mainstream

Freed when constitutional government returned in 1985, Mr Mujica, who is popularly known as Pepe, toned down some of his more radical socialist rhetoric to fight for his ideals as a mainstream politician.

Mr Mujica was released in 1985 after spending 13 years in jail

In a region where left-wing leaders often attack the private sector and blame it for their countries's woes, Mr Mujica and his Broad Front coalition opted for a more moderate approach.

"Mujica's ideas have changed in the last 20 years," explains Oscar Bottinelli, a political analyst in the capital Montevideo. "But he has always been concerned about regular people."

Speaking at his farmhouse on the outskirts of Montevideo, he tells me that he thinks "we have to favour capitalism, so that its wheels keep turning".

The modest home stands next to fields of chard and an abandoned factory he would like to turn into an agricultural school.

He says a quota of resources should be given to the weakest. "But we should not paralyze it [capitalism]; there's a limit," he insists.

Uruguay's economy, boosted by foreign investment, has grown at an average of 5.8% since the Broad Front to power in 2005, World Bank figures suggest, external.

Poverty levels have dropped from around 40% before 2005 to less than 13% today.

Wealth is more evenly distributed now in this nation of 3.4 million people that at any point in the last 30 years, according the government.

'Chaotic style'

Mr Mujica, whose term ends in March, says this is his greatest achievement.

Jose Mujica wearing his trademark black beret

But he is not without critics, who point to his sometimes chaotic leadership, gauche manner and occasionally contradictory statements.

"Mujica's style has become tiresome for some people," Mr Bottinelli says. "They want more certainty."

"He is idealised a lot abroad," sociologist Santiago Cardozo explains. "But his government, like him, was not very organised."

Many Uruguayans admire him precisely because he is sincere and unrefined.

"His strength is not in managing the government, but in understanding the people and reaching their hearts," author Sergio Israel writes in his book "Pepe Mujica - President: An unauthorised investigation".

Mr Mujica still has an approval rate of nearly 60%, according to a recent survey.

And even though he is barred from standing in Sunday's presidential election, he is likely to continue as a political force in congress.

Marijuana dilemma

As president, Mr Mujica has overseen some radical social reforms, including the passage of a groundbreaking law that gives the state nearly total control over the production and sale of cannabis.

Mr Mujica backed a law which bill pioneers state control of the cannabis market

It is a law that polls suggest a majority of Uruguayans disagree with.

Those favouring legalisation have called it totalitarian because it places a limit on the amount of cannabis people can buy and obliges smokers to sign up to a federal register.

Mr Mujica agrees with them in this particular instance.

"They're right," he told me. "But they're my children. And I'm not going to gift them something that turns them into druggies with their eyes popping out of their heads."

Pablo Almiron, a 24-year-old who delivers takeaway food, agree with the president.

"The state needs to control things; that's its job. It's acting for our own good," he says while puffing on a spliff by the waterfront in Montevideo.

The two presidential candidates vying to succeed Mr Mujica may well try to overturn the law.

Luis Lacalle Pou, 41, of the centre-right National Party, openly opposes it and Tabare Vazquez of the Broad Front has also called it into question.

Whoever succeeds Mr Mujica in power will find it hard to match him on the world stage, says political analyst Agustin Canzani.

Simple life

"Mujica has achieved an international image without precedent for almost any Uruguayan of the last few decades," Mr Canzani says of Mr Mujica's image as "the world's poorest president".

Mr Mujica, who donates most of his salary, has been called the world's poorest president

But his simple lifestyle, while widely admired, is not one sociologist Santiago Cardozo would want to follow.

"He's like the modern Uruguayan version of a medieval monk. He makes for a good film."

It is something Mr Mujica himself is well aware of.

"They might look at how I live," he tells me wearing a black beret, fleece and sandals while sitting in his wood-heated living room.

"But they don't follow me. I am a ghost in solitude."

- Attribution

- Published30 June 2014

- Published20 May 2014

- Published9 July 2014