Mexico missing students: Travels on the protest caravan

- Published

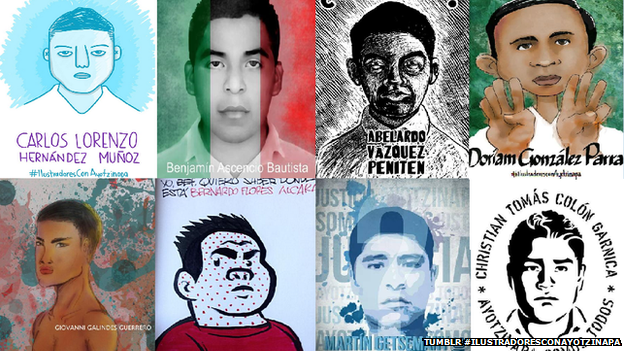

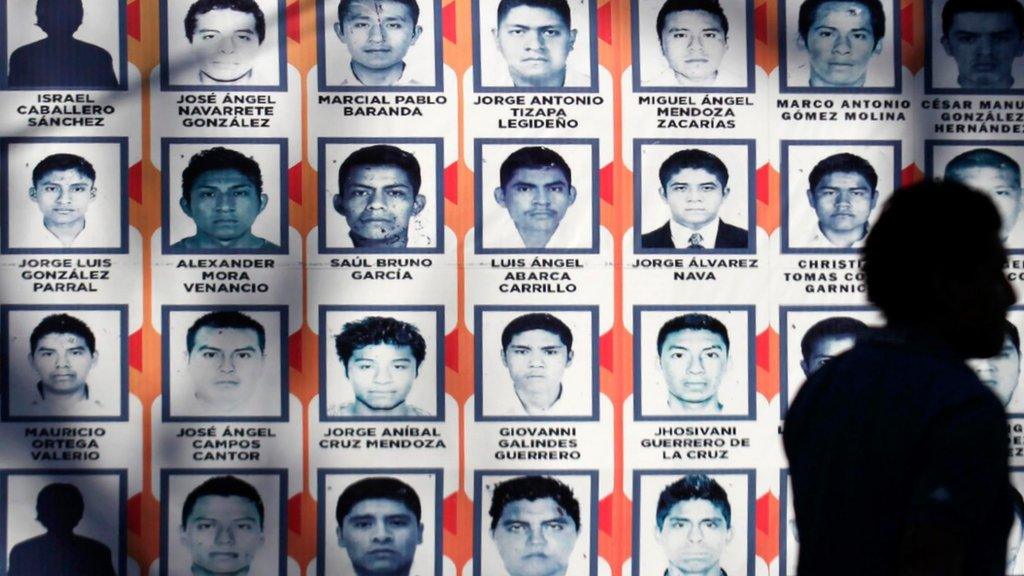

The 43 missing, who the authorities say may have been murdered by a drug gang.

In Mexico, a roadblock is not usually a good sign.

We were travelling with a caravan of friends and relatives of the 43 students that went missing in south west Mexico in late September.

They have been crossing the country to join mass protests in Mexico City against the government's handling of the investigations.

The initial look of consternation from those on board slowly changed to relief, and then joy. The roadblock had been set up by locals from a tiny rural village along the way.

They had forced the caravan to a halt because they wanted to express their support to the parents and friends who have been in anguish for almost two months.

The villagers had drawn up their own posters, with photos of those missing. The encounter quickly turned into a march along the road, blocking transit from either side.

.jpg)

Those on board the caravan have been touched by the support they have received along the way.

There is widespread anger at the authorities over the missing students.

Travellers and locals shared chants and tears.

"This is the third time we've been stopped today," one of the caravan members told me.

"People just want to join us."

The widespread support each one of the three caravans that are crossing the north, south and west of Mexico has received has taken many by surprise.

The anger of the relatives has not only been directed at the government of President Pena Nieto, but also at the left-wing opposition. No-one in the political establishment has been left unscathed.

Oasis

Getting aboard the caravan was not straightforward.

After lengthy negotiations, the parents and friends of the 43 students agreed to give us access to their bus.

The bus, one travelling student explained, had become a sort of oasis where the group could rest, reflect and keep to themselves until reaching the next town.

But for Diana Abarca, whose brother Luis Alberto is one of the missing, the caravan means something else.

A roadblock, usually an ominous sign in Mexico, turned out to be something positive.

"Being here helps me very much, because if I stay at home I get very sad. Here, instead, I feel supported and remain hopeful that my brother will return."

Ms Abarca is travelling with her mother, who is in her sixties. As soon as we get on board she falls asleep. The week-long journey these travellers have faced is taking its toll.

"It has been very hard," says Eucladio Ortega, father of Mauricio, 18, who was part of that group that in late September was last seen bundled by the police into vans.

"But we do this because we want to force the government to give us back our children, all of them."

The Mexican authorities, however, believe there is little hope.

Earlier this month Mexico's Attorney General, Jesus Murillo Karam, announced that it was very likely that some of the badly burnt remains found in one of several mass graves unearthed by diggers in the state of Guerrero were those of the missing 43.

He stopped short of confirming the official death but gave away details of the government's inquiry, which is waiting for DNA tests to be finished in the coming weeks.

Hope endures

This view, however, has not dampened the spirits of the parents we met.

Most have an extremely sad stare. Their pain is visible, and some can't stop the tears when asked about their sons.

The protest tour has helped relatives and friends of the students support each other.

Despite the authorities saying it is likely the students have been killed, hope continues.

But all seem to have the same answer: they are alive.

"When I heard what the government said it just gave me more strength and resolution. Because I know they are alive," says Francisco Lagro, father of Magdaleno, 19, one of those missing.

"It's been almost two months without knowing where they are. We don't know anything and we are desperate. We, as parents, are asking all sorts of things. What are they doing? How are they being held? Do they get any food or water? We have many unanswered questions."

In some cases the anguish is taking its toll within these families.

"My wife doesn't want to come with me to these caravans," says Mr Ortega.

"She simply doesn't want to join me. We have our differences."

The caravans end in Mexico City, and most of these travellers will then go back to their homes, in the state of Guerrero.

It is one of the most impoverished places in Mexico.

"I have to go back to my crop. At some point I need to go back to growing my corn," says Mr Lagro.

- Published7 November 2014

- Published13 November 2014

- Published29 October 2014