Moment of Truth for Brazil's military past

- Published

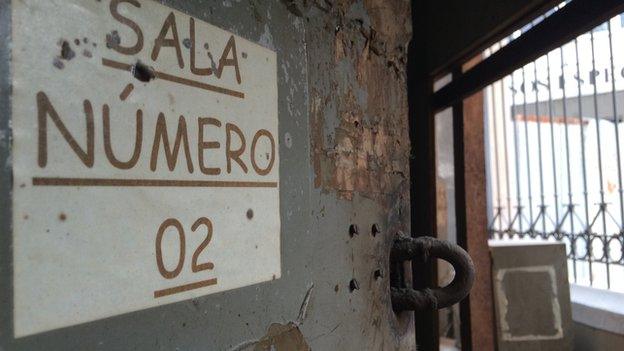

A cell at the Orwellian Department of Political and Social Order or DOPS

The Department of Political and Social Order or DOPS. It is a place as Orwellian and as sinister as the name suggests.

Right in the heart of the modern metropolis of Rio de Janeiro, the former police administration centre, prison and torture chamber has remained largely untouched since the end of the dictatorship in 1985.

In many ways it is a metaphor for how long it has taken Brazil to deal with its demons.

Although Brazil was among the first of Latin America's dictatorships to return to civilian rule it has been one of the last to establish an inquiry - a "Truth Commission" - to find out, for the record, how many people were killed, why and by whom during the years of military rule.

Chile, Argentina, Guatemala and others have all been down this route before.

What I found especially remarkable was that only in recent weeks have the many victims of the former regime been able to return to where they were imprisoned and, in many cases, tortured.

Jane Alencar says there is a feeling of impunity in Brazil

"I can't remember for how many days I was in solitary confinement," Jane Alencar tells me as she surveys the cold, grey cell where she was held at the DOPS.

The former student activist and history teacher was held captive and tortured here on three occasions at the ages of 17, 18 and 21.

"There's a feeling of impunity in Brazil that I think is one of the root causes of all the violence here today," says Jane tearfully.

"No-one has been held accountable for the violent and horrible things that happened during the dictatorship. They've still not been punished."

A soundproofed room at DOPS

Brazil was one of several Latin American nations where the military overthrew democratic governments in the 1960s and 70s.

With support from a considerable part of Brazil's elite and, then, small middle classes the generals said they were countering the very real threat of a communist insurgency.

Over the next 21 years hundreds were killed and thousands were tortured - among them was a young activist in southern Brazil named Dilma Rousseff. Today she is the country's democratically elected president.

Former members of the military, including retired general Gilberto Pimentel, reject accusations that torture was commonplace, that it was official government policy.

Gen Pimentel, is now the president of Brazil's "Club Militar" and is wary of the Truth Commission's brief.

He refers to the events of 1964, when the elected government of Joao Goulart was overthrown, not as a "coup" but as a "popular revolution".

"I have to insist on this point - yes there was torture on our side. It wasn't institutionalised torture but isolated cases," the former army officer tells me.

He then adds: "But there were also cases on the other side. There was terrorism. Revoking the [1979] amnesty law will not bring reconciliation to the country."

Amid a media frenzy, earlier this year a former colonel, Paulo Malhaes, told the commission in some detail how he tortured and killed many victims.

Retired general Gilberto Pimentel rejects accusations torture was commonplace

Under the protection of immunity, Malhaes, who has since died, also gave specific details about training on torture techniques he and others received in the United Kingdom.

He was one of very few former military men to give such candid evidence as the commission had no powers to subpoena witnesses.

It is this, the impunity of those who torture, says former guerrilla Daniel Aarao Reis that lies at the heart of the Truth Commission's work.

"We are a nation of torturers and torture victims," says Aarao Reis, now considered one of Brazil's leading historians and leftist thinkers.

In some ways he agrees the military coup was "justified" because revolutionaries like him were committed to violent overthrow of the capitalist system.

What he objects to is not that there was a conflict, an urban war, but that the regime then resorted to years of institutionalised and persistent torture.

"Torture is almost a Brazilian tradition going back for decades, even centuries," says Aarao Reis. "If we don't have this national debate and our kids aren't educated about this horror, that cycle will continue."

More than 400 people were killed under the military dictatorship.

The controversial amnesty law, for now, protects those on all sides who committed abuses.

Whether or not there will be justice, Brazil is still struggling to deal with its turbulent past.