Alberto Nisman: How and why did Argentina prosecutor die?

- Published

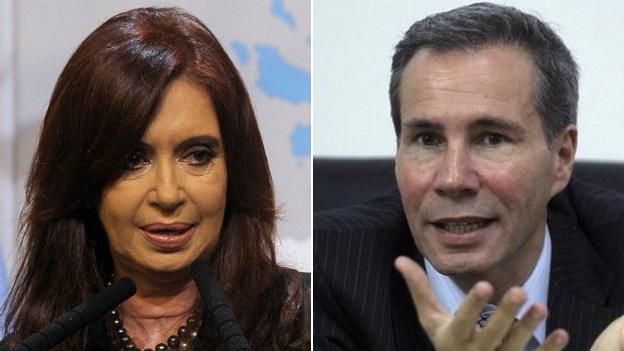

Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner has questioned Alberto Nisman's cause of death

Argentina's populist President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner could not have had a worse start to the new year.

Her final year in office - she is not allowed to stand for re-election - already looks like it will be dominated by ongoing economic uncertainties and a political scandal involving the apparent murder of a former state prosecutor.

While the country's basket-case economy has been a concern for some time, the latter could not have been foreseen. Ms Fernandez's initial response, that Alberto Nisman had probably killed himself, was delivered hours after his body was found in his luxury Buenos Aires waterfront flat.

Amid a long defence of her own role in trying to secure justice for those bereaved by an attack on a Jewish centre in Buenos Aires in 1994, she said she could not imagine "what had driven" Mr Nisman to "do what he did".

A day later the embattled president had completely changed tack.

Issuing an even longer statement via social media, as she is increasingly prone to do - thus keeping out of the public eye - she said the 51-year-old prosecutor had probably not taken his own life.

The president's statement came to the conclusion that, if Alberto Nisman had indeed been murdered, it had been done in a way to get at her and damage her government.

Ms Fernandez initially claimed that Alberto Nisman's death was suicide

While Ms Fernandez's opponents might dismiss those as the inconsistent ramblings of an egotistical leader who always thinks the story revolves around her, there is perhaps some merit to her claim.

Apart from Mr Nisman, the biggest loser in this case is arguably Ms Fernandez herself. As more than one newspaper commentator has pointed out, not a month into 2015 and she has a dead, high-profile public prosecutor on her hands.

Juliana di Tullio, a government deputy in the Argentine Congress, certainly thinks it is part of an elaborate plot to destabilise the president.

"No, she is not at all being inconsistent. She is responding to the facts of the case as they come out," Ms Tullio responds when I suggest to her that the government's new position on Mr Nisman's murder-suicide is a complete volte-face.

The congresswoman denies that Mr Nisman's death and his damning report into the 1994 bombing of the AMIA Jewish cultural centre will irreparably damage an already wounded government. But she agrees that these are difficult days.

The questions that no one can answer at this stage are vital ones: who, if anyone, killed Mr Nisman? And why?

Red-flagging

After decades of brutal military rule, corrupt corporations and equally pliable politicians, Argentines are completely distrustful of their government institutions.

Opinion polls here suggest that an alarmingly high proportion of the population already expect the Nisman murder case to remain unresolved, just as no one has ever been successfully prosecuted for the 1994 bombing or the similar attack against the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires two years earlier.

"People here are very polarised and the government has always played into that game," says political analyst Martin Bohmer.

"Using a friend-and-foe political discourse they have created an environment where some people will believe everything the government says, while others will believe nothing, no matter what," he adds.

"That is why the impact of this death in this moment could polarise Argentine society more than has been the case for many years."

But what about the report itself, the highly charged document that Alberto Nisman had been due to present to a congressional committee a day after his untimely death?

The central charge is that senior government figures were involved in a secret exercise to exonerate the Islamic Republic of Iran for its alleged role in the 1994 bombing, in return for lucrative trade agreements.

It is a well-established accusation that Iran, and its Lebanese-based proxy Hezbollah, were behind the AMIA atrocity, in which 85 people were killed. That accusation was certainly part of Mr Nisman's premise.

Israel, the US and many other intelligence services also say the evidence against Iran is overwhelming, including the "red-flagging" of at least eight senior Iranian officials - wanted for their alleged role in the bombing.

The 1994 AMIA bombing killed 85 people and wounded 300

Whether Iran was to blame or not - and there are many in Argentina, including some local Jewish organisations, who say leads against Syria and other suspects should have been pursued with equal vigour - Mr Nisman's report has been welcomed and dismissed in almost equal measure.

Horacio Verbitzky is probably Argentina's most prominent journalist and human rights campaigner. He has also repeatedly lobbied the government for more effective action in resolving the AMIA case. Mr Verbitzky, however, says Mr Nisman's central argument and the basis for his report simply doesn't stand up.

"He alleges, more than 90 times, that President Kirchner and Foreign Minister Hector Timerman tried to get Interpol to remove the red flags [international travel alerts] against named Iranian officials, as part of this alleged deal with Iran," Mr Verbitzky tells me as we pore over a copy of the prosecutor's report.

He goes on: "But it is simply not true. The former head of Interpol has published an open letter to the Argentine foreign ministry, praising the government's role in pursuing those responsible for the 1994 attacks and saying, quite to the contrary, that Argentina always supported the red flag system. It completely blows a hole in his case."

Even Mr Verbitzky, whose role in exposing and writing about historic human rights abuses and crimes in Argentina is legendary, says he has no idea who is to blame for the prosecutor's death.

"I am not going to speculate because I do not know who killed him but, yes, there are possibly 'dark forces' at work in this country," says the veteran journalist.

By "dark forces" he means powerful figures in the intelligence community and government institutions who have always been there - during and since the military dictatorship.

Conspiracy theories

While some believe that Alberto Nisman was too heavily reliant on foreign intelligence agencies, in particular the US and Israel, others say those invaluable resources have helped to build an overwhelming case against Iran and the subsequent complicity of the Argentine government in trying to cover up its involvement.

Patricia Bullrich is an opposition legislator in congress who sits on the intelligence committee that was due to hear further testimony from Mr Nisman, specifically his allegations about contacts between the Kirchner government and Iran.

Ms Bullrich, who spoke at length with Mr Nisman the day before he died, said that while clearly feeling some pressure from the enormity and political significance of his work, he had been looking forward to delivering his testimony.

"He was accusing Iran, and at least eight named officials, of involvement in the AMIA bombing. Moreover, he showed that our own government lied about the extent of its contact with Tehran as it tried to reach a deal," said Ms Bullrich.

The opposition politician also repeated a perspective favoured by Israeli and some US officials - that it was preposterous even to suggest that Iran should be part of a commission investigating the AMIA attacks.

"Can you imagine if the US government had asked Bin Laden to sit on the inquiry into the 9/11 attacks?" she retorted.

Argentines have been demanding "justice" for Alberto Nisman

It is not even clear if Mr Nisman's report will get its day in Congress but the details are already there for Argentines, and the rest of the world, to read.

In the tumultuous aftermath of the prosecutor's death, Argentina is completely captivated by conspiracy theories, plots and counter-plots.

Not allowing themselves to be forgotten are the victims of the 1992 and 1994 bombings.

AMIA is still there. The headquarters of the Argentine Jewish Cultural Association has been rebuilt on the same spot where a car bomb claimed so many lives. A huge wall, airport-style security and what look like Israeli-trained guards now protect the building.

People like Anita Weinstein are going nowhere. The diminutive but emotionally resilient AMIA official crawled out of the rubble in 1994 in an attack that killed many of her friends and colleagues.

Ms Weinstein said she was "almost knocked off my feet again", when she heard of Mr Nisman's death. But after two decades she has learned not to hope for too much nor to expect justice.

"They tried to kill me but I was determined to live this life. This community is still here and we are still strong, they cannot kill us," she tells me in the small memorial garden to the AMIA victims built within the walls of the new centre.

These are difficult, tense days in Argentina. This is a democracy, albeit a flawed one, that has come through testing times before.

How the government responds to the death of Alberto Nisman and the "dark forces" that challenge its legitimacy will be closely watched.