Why Latin America should not squander the China boom

- Published

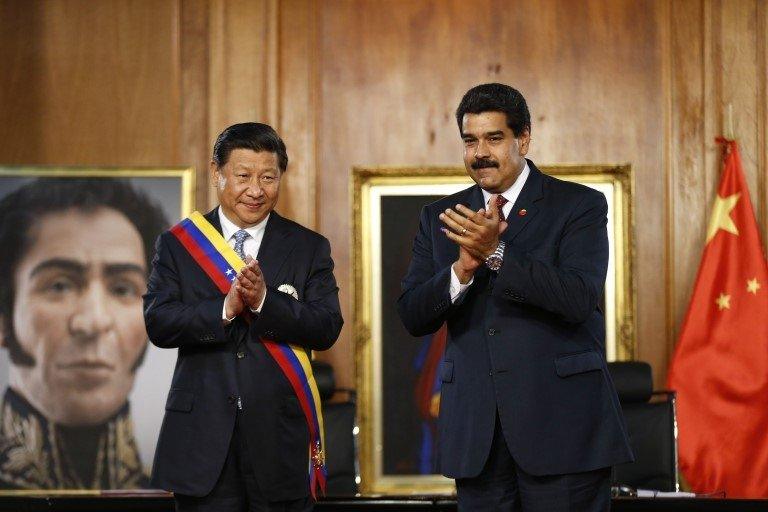

Oil-hungry China has been keen to sign deals with energy-rich Latin American countries such as Venezuela

Aside from the Chinese who helped build the Panama Canal, and the Maoist rebels of Peru who called themselves the Shining Path, China's presence and influence in Latin America was unremarkable until the turn of the 21st Century.

After 2001, when it joined the world economy through the World Trade Organisation (WTO), China quickly began purchasing and investing in Latin American primary commodities.

Today, China is the number one trading partner for some of the region's largest economies, and China's development banks pour more money into the region than the World Bank or the Inter-American Development Bank.

As China has risen, it has been guzzling oil from Venezuela, Ecuador and Mexico to fuel its expanding fleet of cars, lorries, and container ships.

China has wired more than half the world's consumer electronics products with copper from Chile and Peru.

Large shipments of copper leave for China from the Chilean port of Valparaiso

Many of China's new cities have iron ore from Brazil at their core.

As standards of living have risen, the Chinese eat more beef - from cattle that are fed soya beans from Argentina and Brazil.

In turn, Chinese companies have flocked to the Americas to invest in these commodities, backed by blank cheques from China's state-run development banks.

Voracious appetite

In many ways, China's voracious appetite for Latin American commodities has been a saviour for the Americas, especially in the wake of the global financial crisis.

Argentine soya bean growers have benefitted from increased Chinese demand

Latin America rode the coattails of the boom in China, growing at an annual rate of 3.6% from 2003 to 2013.

That stands in stark contrast to the previous two decades dominated by the so-called "Washington Consensus", the belief that orthodox economic policy, complete opening of markets, and the reduction of the role of the state were the best ways for developing countries to grow.

Under the "Washington Consensus", growth was a much slower 2.4%.

New shores

In the wake of the 9/11 attacks and then after the global financial meltdown that originated in the US, Washington turned to other shores.

So Latin America has quickly become incredibly strategic for China - as a source for many of the key natural resources it needs to grow its economy and the appetites of more than a billion people.

That is why last month China hosted the first ministerial conference of the China-Celac Forum.

China pledged to increase trade with Latin America to $500bn at the China-Celac Forum earlier in January

Celac, or the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, was formed in 2011 and comprises 33 countries.

Alongside a host of co-operation agreements, China pledged to increase trade with Latin America to $500bn (£329bn) and to invest upwards of $250bn over the next decade.

China also pledged $20bn (£13bn) in loans for China-Latin America infrastructure projects and created a $5bn China-Celac Co-operation Fund.

Such trade and investment will be very welcome in a region projected to see slow growth over the next few years.

New challenges

With the new friends come new challenges, however.

Chinese trade and investment in primary commodities caused prices and exchange rates to skyrocket in the region and made Latin American manufacturing industries less competitive on a global scale.

Textiles, car-making, electronics and other companies from Brazil and Mexico have lost significant market share in world and regional markets, and have attracted much less investment.

Moreover, natural resource exploitation in Latin America goes hand in hand with environmental degradation and social conflict.

Mining, oil exploration, and large-scale farming activities often necessitate the clearing of forests and the pollution of waterways; they are found in areas where many of the world's richest indigenous cultures reside.

Logging is taking its toll on indigenous communities in Peru and Brazil

There are global advocacy campaigns reeling over Chinese oil exploration in the Ecuadorean Amazon and hydroelectric dams near biosphere reserves in Honduras.

Latin American governments fell far short in capturing their China windfall and investing some of the proceeds into industry and innovation, into people, and into protecting the environment.

According to research by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), although the China-led commodity boom was among the longest and most lucrative in the region's history, most Latin American countries saved less of these windfalls than they have in past booms.

Latin American countries will do well to put the proper policies in place as these pledges for new trade and investment materialise.

Without such policies, the region will suffer from lost growth opportunities, lost elections, and a degraded environment.

Kevin P Gallagher is an associate professor of global development policy at Boston University's Pardee School of Global Studies, where he co-directs the Global Economic Governance Initiative.

His forthcoming book on China and Latin America will be published by Oxford University Press and is tentatively titled Capitalizing on the China Boom: China's Rise and Prospects for Prosperity in the Americas

- Published9 January 2015

- Published9 January 2015

- Published22 July 2014