The Japanese-Peruvians interned in the US during WW2

- Published

Blanca Katsura and her family were among 1,800 Japanese-Peruvians to be interned in the US (photo courtesy of Blanca Katsura)

Blanca Katsura will never forget the night of 6 January 1943.

She was 12 at the time and living with her parents and two siblings in northern Peru.

On that night, two officials came to their home and took away her father.

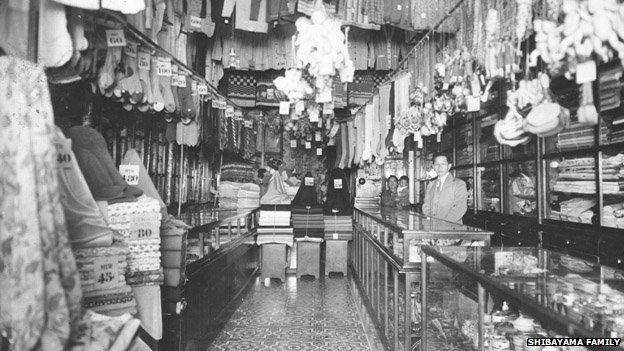

Mr Katsura, who owned a small general store, was arrested because he was part of Peru's prosperous Japanese community.

"My father told them he hadn't done anything wrong, but they didn't listen to him," she recalls.

Latin American draw

Japanese people began migrating to Peru in considerable numbers at the end of the 19th Century, drawn by opportunities to work in the mines and on sugar plantations.

By the 1940s, an estimated 25,000 people of Japanese descent lived in Peru. Many had become lawyers and doctors, or owned small businesses.

Many Japanese-Peruvians did well in their new homelands and set up successful businesses (photo courtesy of Art Shibayama's family)

Their prosperity, further fuelled by racism, soon triggered anti-Japanese sentiment in Peru, Stephanie Moore explains.

Ms Moore, a scholar at the Japanese Peruvian Oral History Project, says after the outbreak of World War Two, the Japanese community in Peru became a target, and their assets were confiscated.

"In May 1940, as many as 600 houses, schools and businesses belonging to citizens of Japanese descent were burned down," she says.

Following Japan's 1941 attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, the US government asked a dozen Latin American countries, among them Peru, to arrest its Japanese residents.

Records from the time suggest the US authorities wanted to take them to the US and use them as bargaining chips for its nationals captured by Japanese forces in Asia.

Deported

Mr Katsura was among the 2,200 Latin Americans of Japanese descent who were forcibly deported to internment camps in the US.

Blanca Katsura, who is now 83 and lives in Northern California, remembers how she learned of his fate.

"A month after my father was detained, he sent me a letter because it was my birthday," she recalls.

"He had been taken to Panama from where they were planning to send him to the US," she adds.

Six months later, Blanca Katsura's mother decided to take her three small children to the US to search for her husband.

"When we arrived in New Orleans after a month-long trip, they confiscated our passports and then sent us by train to the Crystal City camp."

As many as 4,000 people were interned during World War Two in this camp in Texas run by the US Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Most of the detainees were of Japanese descent, although some German and Italian immigrants were also held there.

Crystal City Internment Camp was located 180 km (110 miles) south of San Antonio in Texas

It was at Crystal City that Blanca Katsura was reunited with her father. "I was shocked, he had lost so much weight," she remembers.

For the next four years, her family lived in the barracks at the camp.

Her memories of that time are not particularly traumatic, she says.

"Being a child at the time time, I had no worries and made lots of friends.

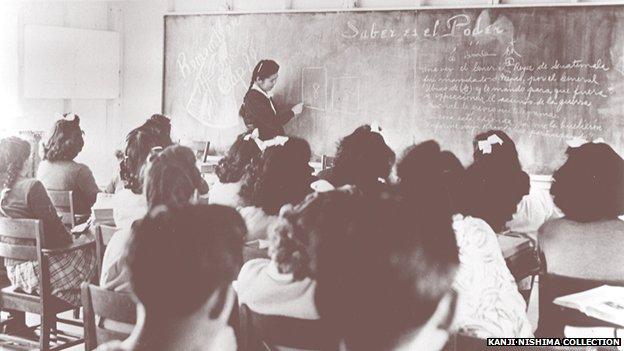

"We were able to go to school and learn Japanese," she adds.

Children in Crystal City attended classes inside the camp (photo courtesy of the National Japanese American Historical Society)

Ms Katsura says she later learned that the camp authorities were keen for the children to learn Japanese so they would be able to speak the language once they were deported to Japan.

Really bitter

Chieko Kamisato's memories of life at Crystal City are less positive.

Chieko Kamisato now lives in Los Angeles (photo courtesy of Chieko Kamisato)

"You could call it a concentration camp, because we were surrounded by barbed wire fences and guards with guns," she says.

"We couldn't go out at all, although we were free to move around inside," she recalls.

"My parents were really bitter about the situation because they were forced to come to the US. They had no choice," she says.

Ms Kamisato's father had moved to Peru from Japan in 1915 and had worked hard to open a bakery in the capital, Lima.

Now 81, she lives in Los Angeles.

Reparation debate

Of the 2,200 Latin Americans of Japanese descent to be interned in the US, 800 were sent to Japan as part of prisoner exchanges.

After World War Two ended, another 1,000 were deported to Japan after their Latin American home countries refused to take them back.

While there were also Germans interned in Crystal City, the majority were of Japanese descent (photo courtesy of Art Shibayama's family)

Ms Katsura's and Ms Kamisato's families successfully fought deportation and were eventually allowed to remain in the US.

In 1988, then-President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act and apologised on behalf of the US government for the internment of Japanese-Americans.

Under the act, the government paid tens of thousands of survivors of the camps $20,000 (£13,000) each in reparation.

But Japanese-Latin Americans did not qualify for the payments because they had not been US citizens or permanent residents of the US at the time of their internment.

Outraged, they filed a class-action suit and 10 years later, the US government agreed to pay them $5,000 each.

Most accepted, but a small group headed by camp survivor Art Shibayama decided to hold out, demanding to be paid the same as Japanese-Americans.

Blanca Katsura says that even though her childhood at the camp may not have been traumatic, no amount of money can compensate her family for its loss.

"My parents wanted to go back to Peru but couldn't. They missed the life they had there," she recalls.

"The Peruvian government sold us out to the US government and that is not a very nice feeling. How would you feel about it?"

Related topics

- Published18 February 2012

- Published7 December 2011

- Published28 March 2011