Brazil 'security crisis': The Rio police on the front line

- Published

In Rio de Janeiro 114 police officers were killed last year, according to the Civil Police union Sindpo

In Brazil, more than 50,000 people are murdered each year - including scores of police officers. In Rio de Janeiro alone, 114 police were killed in 2014, according to the civilian police union Sindpol.

The human rights group Amnesty International says , externalthere is a "public security crisis in Brazil". It is calling for a national plan to drive down the murder rate.

As well as calling for action against the use of lethal force by police, Amnesty also points out the difficulties officers face, on and off duty.

Beth McLoughlin spoke to three officers about their experiences and concerns.

Roberta Guimaraes, 32

A soldier in the military police, responsible for law and order on the streets and in the units of police pacification (UPPs) in Rio de Janeiro.

"My husband is in the military police and I found this hard to accept at first. I saw them as oppressors, but he is very calm - a good person. In the end, I realised they were people like any other.

"When I joined myself, I fell in love with the work, bringing the police closer to the community. A lot of military police come from favelas (shantytowns) themselves. My father was born in a favela, but some people still think think that it's only criminals who live there.

"In the past, women officers weren't accepted but there is less resistance now.

"I change into my [civilian] clothes here [at the UPP base] and don't go home in my uniform. That's not through lack of pride [in the uniform], but for safety. But I see myself as a member of the military police 24 hours a day. Some of my friends accept this and others don't. We have seen the some of the worst things in life and these things stay with you.

"Of course I am afraid. The fear keeps me alive. For the next 16 years at least, I have to stay alive for my son's sake. We have to use our fear in our favour."

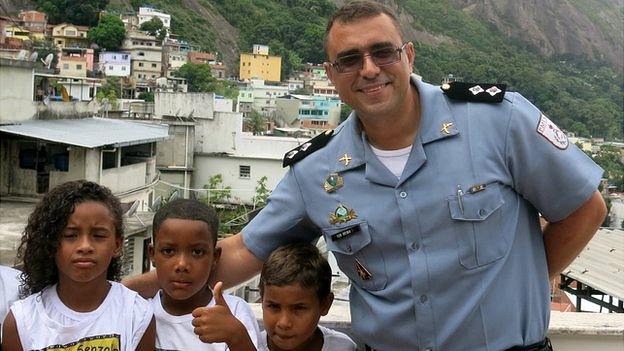

Carlos Veiga, 35

A lieutenant in the military police at the UPP in Vidigal favela.

"If you thought about the danger, you would give up.

"My father was a police sheriff. The law is the same for everyone, it's non-negotiable. But people are influenced by their environment, like I was by my father. There are some crimes anybody could commit, it's just a question of circumstances.

"The state shouldn't kill citizens. But we are only human, and sometimes if your emotions get the better of you, you will lose control. But this will put you on the same level with the criminals.

"Military police officers get only six months' training and investment [in the UPP force] is not what it should be. But low salaries are not to blame for corruption. I tell my officers: do what you believe in, don't think about the salary.

"We have heroes here as well as psychopaths. We have people who would save the life of a man he doesn't even know and who would probably badmouth about him afterwards."

Gilvan Ferreira, 53

An inspector with Rio de Janeiro's Civil Police, which is responsible for investigating crimes. He is also a psychologist.

"I was born in the Vila Cruzeiro favela, and all my uncles were in the police. When I was six, I used to cycle around dressed up in a military police uniform with a white helmet and a plastic pistol. You couldn't do that now as the area is dominated by organised crime.

"I work at the police homicide division in Rio, interviewing suspects, witnesses, and victims' families, and I teach at the Police Academy. Our work is preventative, understanding crimes and their causes.

"The hours are long, but I would hate to wake up one day and not be in the police. If you do what you love, it's not work.

"We have a saying that a police officer can't make a mistake. He is a different kind of professional. The wrong decision could put someone in jail or a cemetery.

"I have faith that one day, police officers will no longer be hunted by criminals, and we will live in a society with more tolerance on both sides."

The future for Brazil's police

In the wake of the Amnesty International report, Rio's Civil Police announced that police killings during "acts of resistance", where a suspect is being pursued, would now be investigated by the homicide division instead of by officers in local headquarters.

But Patricia Silva from the pressure group Redes de Comunidades Contra a Violencia (Network of Communities Against Violence) thinks it takes more than that to reduce police violence.

She argues that police culture and the way officers view their community needs to change fundamentally.

"Police still regard favela residents as their opponents," she explains.

She thinks that more needs to be done to demilitarise a force which has come to resemble soldiers more than police officers and has also called for and an end to impunity for senior officers who commit crimes.

- Published18 March 2014

- Published21 March 2014