Panama tackles gangs with carrot-and-stick approach

- Published

Members of the Rich Kids gang say they have changed for good (the faces of former gang members have been blurred to protect them from being targeted by rival gangs)

"They killed one of our guys and we didn't do anything, no vengeance, nothing, nothing at all," says 18-year-old Jesus.

"We really want to change, we want a new life," he insists.

Jesus is a member of the now defunct Ninos Ricos (Rich Kids) gang in the Panamanian port city of Colon.

A year ago, the Rich Kids heard about an amnesty which newly elected President Juan Carlos Varela was offering gang members willing to join a re-socialisation programme called Safer Neighbourhoods.

Carrot and stick

The president's offer followed the classical carrot-and-stick approach: incentives for those willing to sign up to the three-year programme and the threat of long prison terms for the rest.

The Rich Kids had already been hit hard by a police crackdown, and with 38 of the 65-strong gang in jail, the remaining 27 sat down to discuss their options.

Police can now concentrate on catching recalcitrant gang members, the government says

Jesus had joined the gang at the age of 14.

He insists he never killed anyone, but admits to taking part in shoot-outs with rival gangs.

Since many of the gang members were fathers of young children and afraid of long jail terms, they made a unanimous decision to take up the president's offer.

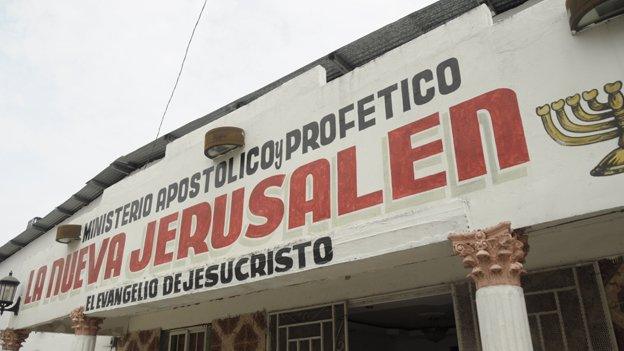

In a local evangelical church, they now attend daily classes teaching them basic values and life skills.

But just months into the programme, they were faced with the hardest test yet for their resolve to change.

'No revenge'

It came one Sunday morning as they were leaving church and about to set up a makeshift goal in the street for a game of football.

Rival gang members drove up in a car and fired at them, killing one of their group.

One of the ex-gang members was killed while he was playing football outside a local church

Colon on Panama's Atlantic coast is notorious for its high homicide rate

But instead of reacting to the assault as they would have done in the days before the programme, they just "sat still and did nothing to avenge" the murder of their friend.

The programme tries to teach former gang members not just how to change their behaviour but also how to make a valuable contribution to society.

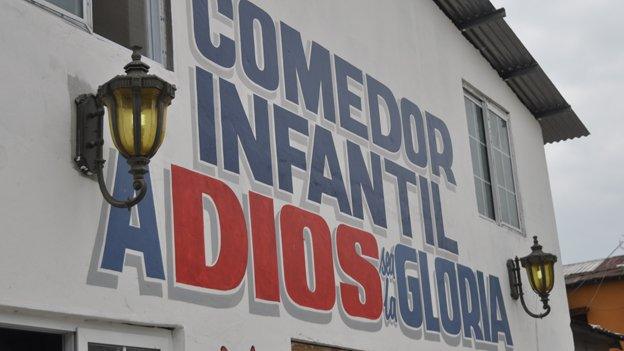

Having been taught bricklaying and plumbing, they have put their newly acquired skills to the test by constructing a dining hall for needy children.

Former gang members put their skills to the test working on social construction programmes

One of the projects Jesus has worked on is building a dining hall for needy children

Drills for guns

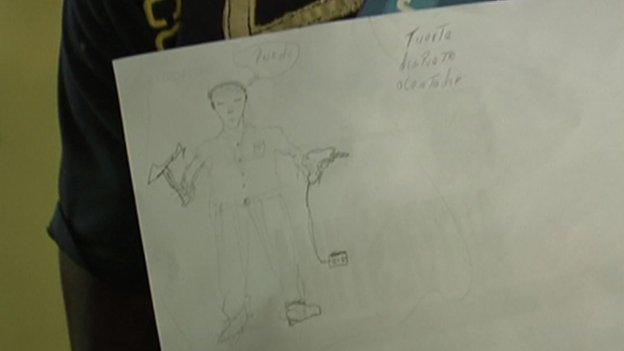

In a church a few streets away, Taylor, another former gang member enrolled in Safer Neighbourhoods, shows me a picture he has drawn.

"The pastor gives us homework. He told us to draw an image of how we see ourselves in the future," he explains.

At first glance it looks like a stick figure with a machine gun.

But on closer inspection, it turns out to be a drill, and what looked like a machete is a spirit level.

Taylor's dream is to become an electrician

Taylor assures me that if I ever wanted a house in Panama, he would be able to build it from scratch.

"I've just finished a course on roofing, so there," he says.

Controversial move

The programme has not been without controversy and has faced scathing criticism by the Panamanian media.

In addition to training and psychological support, those joining the programme receive $50 (£32) worth of food stamps per week.

Some critics regard this as a reward for criminal behaviour.

The programme is up and running in the cities of Colon, San Miguelito and Panama City

Police officers supervise the former gang members when they carry out social work

But Security Minister Rodolfo Aguilera is adamant that the programme's benefits are already outweighing its costs.

About 2,000 youngsters ranging in age from 18 to 35 have enrolled - a third of the estimated number of gang members in Panama.

Official figures suggest that there has been a 31% reduction nationwide in high-impact crimes such as murder, assault, rape and robberies in the first quarter of 2015 compared to the same period last year.

In Colon, where 90% of gang members are estimated to have enrolled in Safer Neighbourhoods, there has been no murder for two months.

While most gang members are male, some women have also signed up

Before the programme started, between one and two people were killed here per week on average.

Drop outs

Mr Aguilera acknowledges that the crime reduction may well be linked to wider economic and social factors.

But in areas where the scheme has not yet been introduced, crime rates have at best stagnated, he insists. In some cases, they have even gone up.

Crime rates have stagnated or even risen in areas where the programme has not yet been introduced

Not everyone finishes the course, though. An estimated 40% have dropped out.

They either failed their exams or did not want to follow the routine imposed by the programme.

Four hours a day of life skills classes and religious instruction, in addition to vocational training, sports and work schemes such as clearing weeds from school playing fields, do not appeal to all gang members.

Attempts are made to persuade those who drop out to rejoin the scheme, but the minister has a warning for those not willing to change.

'Firm hand'

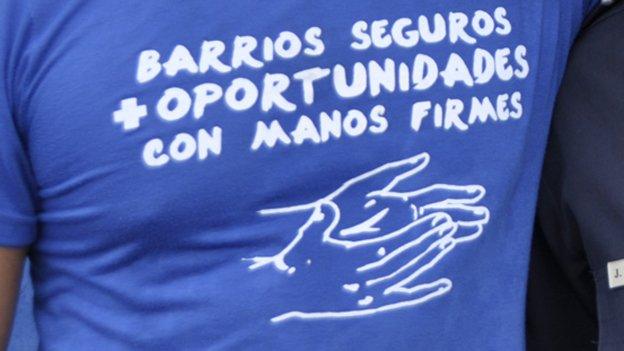

The programme's full name of "Safer Neighbourhoods with More Opportunities and a Firm Hand" carries a clear message, he says, emphasizing the "firm hand" approach.

Former gang members proudly wear T-Shirts with the programme's logo

With fewer gang members on the streets, the police can concentrate their efforts on the recalcitrant ones.

Angel, 31, was until recently one of them.

The prospect of going to jail was no deterrent, he says. "It only made things worse."

Eight bullet holes and just as many machete wounds on his body illustrate what he means.

In a complete turnaround, he is now singing the praises of the Lord.

'New man'

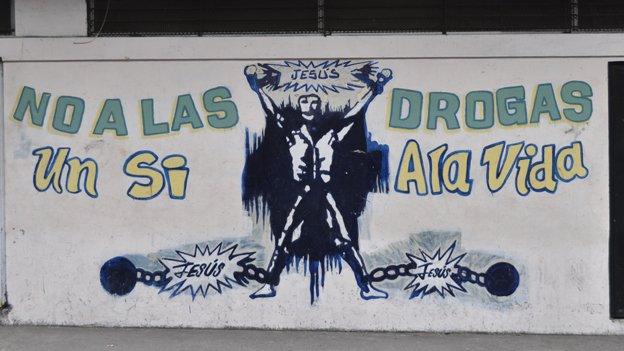

The religious aspect of the programme was not one originally envisioned by the government.

Social workers and psychologists found that having no respect at all for their victims, the law or their elders, the only authority accepted by many gang members was a higher being.

So they got local evangelical pastors on board, who now run many of the classes.

For Angel, it appears to have worked.

He is reluctant to talk about his two decades of criminal activity, and only nods when asked about the rival gang member he killed.

But he professes to be a new man since having found God, totally dissociating himself from his past.

And as if to demonstrate his conversion, he breaks into a song praising God, with the gang members he once led joining in the impromptu rendering.

Angel (in the pink shirt) convinced his gang to hand in their weapons

With one of them swinging a guitar around while not producing a single chord and two more banging the drums with much dedication but little rhythm, it is evident that their musical skills lack refinement.

But their enthusiasm is overwhelming and it comes as little surprise that the government would rather have them clutching guitars than waving around guns.