Impunity feared in Mexico photojournalist's murder

- Published

Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world in which to be a journalist

"No pasa nada" is a saying you often hear in Mexico.

It means "nothing happens" but people often use it reassuringly as in: "Don't worry about it, it's nothing."

When it comes to solving murders, "no pasa nada" is a pretty accurate description.

According to Mexico's statistics institute, 98% of homicides in 2012 went unsolved.

The culture of impunity is frightening.

The 31 July murder of photojournalist Ruben Espinosa along with four women in a middle-class neighbourhood of Mexico City is a crime that many fear will once again go unsolved.

Ruben Espinosa worked for eight years in Veracruz as a photojournalist

Mr Espinosa worked as a photojournalist in the eastern state of Veracruz for the investigative magazine Proceso, among others.

He had recently left Veracruz for Mexico City because of safety fears.

Veracruz is the most dangerous place to be a journalist in Mexico, which itself is deemed one of the most dangerous countries for journalists.

Nationwide, 88 journalists have been murdered since 2000, according to free speech organisation Article 19.

Fourteen journalists from Veracruz state alone have died since current governor Javier Duarte took office in 2010.

That makes Veracruz the most lethal state for journalists out of Mexico's 31 states and its federal district.

No love lost

Relations between the Veracruz governor and the media have been tense. In July, Governor Duarte accused some journalists of having criminal ties.

He went on to warn them to "behave", arguing that if anything were to happen to them, it would be him who would be "crucified".

Some local journalists saw this as a thinly veiled threat against them.

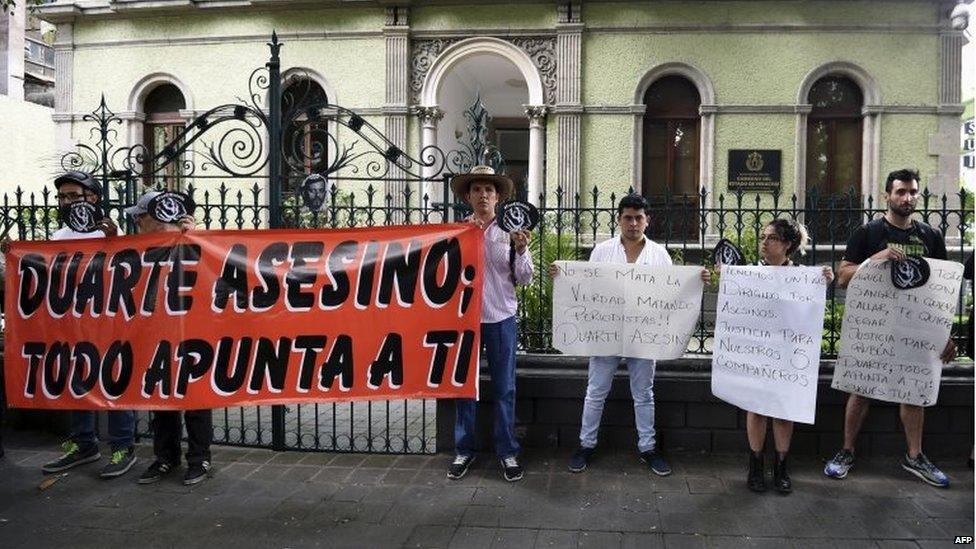

Some of Mr Espinosa's colleagues have blamed Veracruz Governor Javier Duarte for the killing

Human rights investigator Patrick Timmons says that while Veracruz may currently be the most risky place for journalists in Mexico, other states are not immune from violence against the media.

"We have to understand that what we're seeing in Veracruz has happened in other states and it will happen in other states too," he warns.

Mexican authorities investigating the multiple murder said they were keeping all lines of investigation open, including robbery.

Mexican journalists say they are being silenced by threats and intimidation

But friends and relatives of Mr Espinosa think he was deliberately targeted, pointing to the execution-style nature of the killing.

All five victims were shot in the head. Mr Espinosa's body showed signs of torture and three of the four women were raped.

So far, one suspect has been arrested.

Investigators said his fingerprints had been found at the crime scene and matched to a database which showed he had a criminal record for rape and assault.

But Emily Edmonds-Poli, associate professor of political science at the University of San Diego and author of a paper on violence against journalists in Mexico, is sceptical.

"That's so old-hat in Mexico, you pick up the nearest criminal and you accuse them of the crime," she said.

"I don't believe anyone is fooled by that," she added,

Drugs war or politics?

Many of the journalists killed in Mexico reported on organised crime and drug trafficking, considered inherently risky beats.

But Prof Edmonds-Poli thinks their killings should not be dismissed that easily.

"Many of them have covered corruption beats or politics, they are not necessarily chasing ambulances and trying to report on cartel activities," she argues.

She says that "it's the nexus between drug-trafficking organisations and the government, and that's why this really isn't solely a drug-related issue".

"It's about how the state deals with being exposed," she adds.

No safe haven

The fact that Mr Espinosa was killed in Mexico City after having fled Veracruz, where he had received death threats, is seen by many as a dark development.

Journalists say the murder in the capital is a worrying development

Mexico City had for several years been seen as a safe haven, a bubble for journalists.

But that bubble has now burst.

Free speech group Article 19 argues that Mr Espinosa's murder marks a new level of violence against journalists in Mexico.

"If you get pursued into Mexico City, that shows another level of determination on the part of people who are interested in silencing journalists," said Emily Edmonds-Poli.

Ruben Espinosa's murder shows that it is no longer true that in Mexico City "no pasa nada".

- Published4 August 2015

- Published5 August 2015

- Published2 August 2015