Struggling with sexism in Latin America

- Published

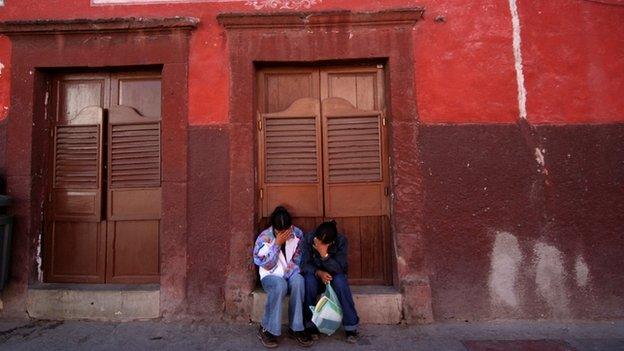

I have one particularly large wrinkle between my eyebrows I put down to scowling while living in Mexico in my 20s, trying to ward off the hisses and catcalls in the street.

There was one day, though, when I dropped the scowl and chose another tactic.

A scorching summer afternoon, I had popped into a corner shop to buy some water.

As I waited to cross the road, two men in a van started to shout out remarks about my body.

I tried to ignore it, but then something inside me snapped.

I removed the lid of my water bottle and squeezed the entire ice-cold contents in their faces.

The comments certainly stopped, and I felt a whole lot better.

A few years later, I moved to the Middle East. At first, it felt like the polar opposite of Latin America.

The cliched image of women in Saudi Arabia...

...compared with that in Brazil

A region where men and women do not always interact and where the cliched image of a woman veiled from head-to-toe in black could not be further removed from the equally cliched image of women in bikinis during the Rio Carnival.

But look beyond the obvious, and the two regions have much in common when it comes to the role of women.

Protecting women's honour is a fundamental part of Middle Eastern culture, and it is often used as an excuse for preventing women from having equal rights as men.

You need a man to drive you places in Saudi Arabia, and you need the permission of a male guardian to travel.

One by one, rules limit the way women can live freely.

I often thought about how this compared with the machista culture so prevalent in Latin America - a concept that emphasises manliness.

My Portuguese teacher once tried to explain the difference between sexism and machismo. "Sexism is bad," he said, "but machismo isn't - it's a way of protecting women." I am still struggling to find the positive differences to be honest.

Whether it is honour or so-called machismo, the end result is the same. Women become second-class citizens.

But it can be a hard one to crack, says feminist Catalina Ruiz-Navarro who is Colombian and lives in Mexico City. Men in Latin America are often proud of being machista and many women like their "protective" macho men.

"It's a very Latin belief," she says. "If he isn't being jealous and possessive he doesn't want to be with you and he doesn't love you. Men are taught to be this way and women are taught to want it."

Brazil and Argentina both have female presidents

What is freedom?

Since moving back to Latin America, I have lost count of the times I have been asked what it was like as a woman living in the Middle East. "It must have been so hard," people say. To be honest, living in cities such as Mexico City can often feel harder.

While many of my female friends have smiled knowingly at my response, others flatly reject it. "Women here are free," said one. "What's wrong with being complimented in the street? They are appreciating our beauty," said another.

If your "freedom" on the way to work is curtailed by threatening sexual comments, and you are made to feel like an object and not a human being, I question whether that is true liberty.

Having recently spent some time in the Cuban capital, Havana, constantly being hissed at, the word that comes to mind is more "trapped" than "free".

Depressing data

Wherever you look, the statistics are depressing.

In Egypt, female genital mutilation has been banned since 2008 - but government figures show that over 90% of women in Egypt under 50 have experienced FGM.

A 2013 UN study indicated that 99.3% of Egyptian women had experienced some kind of sexual harassment., external

But dig around and the statistics in Latin America are pretty grim too.

The public transport system in Colombia's capital, Bogota, was recently ranked the most dangerous in the world for women

A recent survey by YouGov, external for the Thomson Reuters Foundation indicated that of the most dangerous public transport systems for women in the world, the top three were in Latin America:

Bogota

Mexico City

Lima

In Mexico City, they have tried to curb harassment by introducing women-only carriages on the metro, although to mixed success - I often see men getting on in those areas, ignored by authorities.

Women and the law

Latin America has made massive steps - it has female leaders in several countries including Argentina, Chile and Brazil. And Latin American countries signed the Convention of Belem do Para in 1994, which committed countries to improving women's rights and influenced several laws on violence against women.

But law is one thing, reality is another.

In neither Latin America or the Middle East does the law adequately protect women against sexual violence.

In the United Arab Emirates there have been cases of women who have reported rape and ended up being thrown in jail, accused of extra-marital sex.

But countries such as Brazil and Mexico are in the top 10 most dangerous countries to be a woman, external.

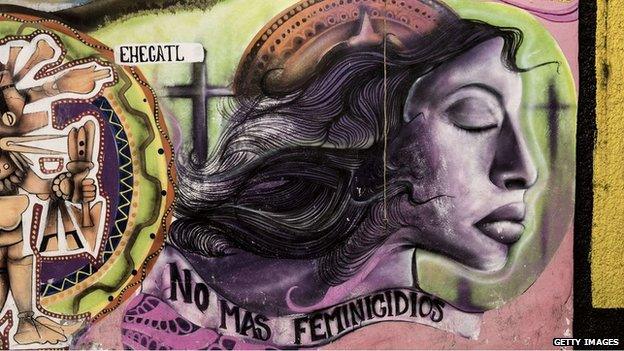

Mural reading: "No more femicides", in Ecatepec, Mexico State

Dangers faced by women in Latin America

According to the UN, a woman is assaulted every 15 seconds, external in Brazil's biggest city, Sao Paulo

In Mexico, it is estimated more than 120,000 women are raped a year - that is one every four minutes

According to Mexico's Femicide Observatory, external, 1,258 girls and women were reported to have disappeared between 2011 and 2012 in the State of Mexico alone. Between 2011 and 2013, 840 women were killed, 145 of these killings were investigated as femicides

Some 53% of Bolivian women aged 15-49 have reported physical or sexual violence in their lives, according to the Pan American Health Organization , external

About 38% of women in Ecuador say wife-beating is justified for at least one reason

This is not an essay limiting the issues of sexism to Latin America and the Middle East. Far from it. This is about my experience working in both Latin America and the Middle East as a woman - the parallels, the peculiarities and the paradoxes.

I fully realise this is a global issue that has many realities in different societies - rich and poor, conservative and liberal. Indeed, many of my friends in the Middle East and Latin America look at Europe as a place to learn from.

But not long ago a British colleague in his 30s showed surprise when I told him my partner was relocating because of my job. He replied: "But surely when you have babies, you will start following him?"

He was lucky he did not get that bottle of water over his face too.

- Published22 June 2015

- Published23 March 2011

- Published31 October 2010