Missing students: Mexico's violent reality

- Published

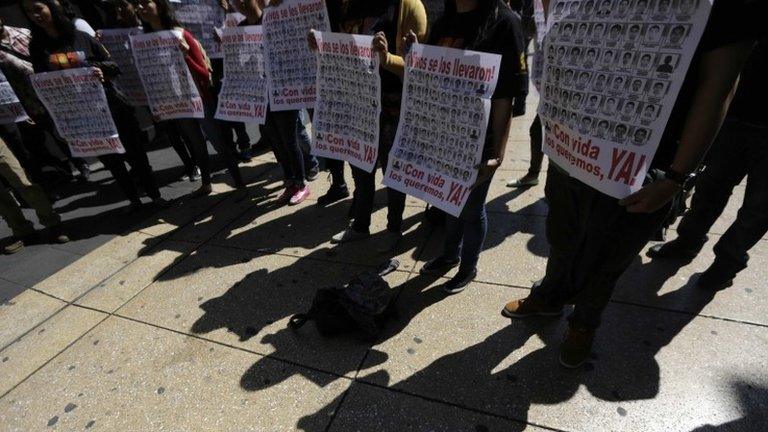

Many have taken to the streets in support of the missing students

"They were taken alive, we want them back alive."

It is a chant that has been repeated over and over again by the families of the 43 students, ever since they were forcibly disappeared on the night of 26 September last year.

Corrupt police and criminal gangs are thought to be behind their disappearance.

On Saturday, more than 15,000 people marched through the centre of Mexico City in solidarity with the families of the missing.

Some carried posters that read: "Not one more disappearance, not one more death - out Pena Nieto."

Many feel very strongly that the government of President Enrique Pena Nieto is to blame.

The number 43 is etched into peoples' minds. It is spray-painted onto walls and lamp-posts. Shaved on to protesters' heads.

But it is hard to get accurate figures of the total number of casualties caught up in Mexico's drug violence.

Conservative estimates put the number of missing at more than 23,000.

Protests have drawn big crowds

It is thought that about 100,000 have been killed in the past decade.

Earlier this year, the International Institute for Strategic Studies published an armed conflict survey, external that put Mexico in third place after Syria and Iraq when it came to fatalities.

But how did it get to this?

"Mexico has always been violent," says Javier Sicilia, a poet and activist whose son was killed in an episode blamed on drugs gangs.

"The revolution in 1910 cost the lives of a million people, many of them sacrificed in a brutal manner."

In the years after the revolution, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) held a tight grip on Mexico - it governed the country for more than 70 years.

"It wasn't a dictatorship, but it was a kind of dictatorship," says Enrique Krauze, a Mexican writer and historian who said that all the violence - legitimate and illegitimate - had been controlled by the president.

"That's not to say Mexico didn't have a violent underworld, but it wasn't known about, or it was controlled."

Political instability

The PRI's seven-decade reign came to an end in 2000, when Vicente Fox of the National Action Party (PAN) won the elections.

"Democracy fortunately arrived in Mexico, but it decentralised power," says Mr Krauze.

"The pyramidal power structure dispersed and unlocked local powers - governors, mayors - but also criminals."

President Pena Nieto has been the subject of angry protests

With the loss of the old system, there was no new structure compatible with a democratic state, says academic Lorenzo Meyer. "The power vacuum is filled by organised crime."

Ioan Grillo, author of El Narco: The Bloody Rise of Mexican Drug Cartels, says the violence escalated in 2004.

It was about this time that drug routes to the US changed.

Armed conflicts:

2008: 63 armed conflicts around the world led to 56,000 fatalities

2010: 55 armed conflicts, 49,000 fatalities

2012: 51 armed conflicts, 110,000 fatalities

2014: 42 armed conflicts, 180,000 fatalities

Source: International Institute for Strategic Studies

US law enforcement efforts meant that cocaine that used to pass through the Caribbean moved to Mexico.

"Mexican cartels would take cocaine and bounce it over the 2,000 mile border with the United States," says Mr Grillo.

"That brought more money to Mexico. And with more money, it allowed cartels to buy more guns, to bribe more police, to train and pay more assassins."

Mexico also stopped being a country that just transported drugs, it became a producer.

Guerrero, the state where the 43 students disappeared, produces huge amounts of poppies to satisfy US demand for heroin.

War on drugs - a failed policy?

Everybody agrees that the violence intensified when Felipe Calderon was elected president in 2006.

Almost immediately, Mr Calderon initiated his so-called "war on drugs" - a strategy that used military force to disrupt Mexico's drugs cartels.

The drug cartels in Mexico are heavily armed

The idea was to clamp down on violence.

Instead, it seemed to fuel it. And President Enrique Pena Nieto, it seems, has done little to change tack.

Denise Dresser, professor of political science at ITAM in Mexico City, compares taking on the drug cartels to "stepping on mercury".

Cartels multiplied and expanded their grip, extorting people and "becoming parallel governments" in some places.

"The drug market is one of the few functional markets in this country," says Ms Dresser.

"It's a market that produces, conservatively speaking, $50-$60bn a year in profits.

"The Mexican state doesn't have the tools, the ability and I would even say the willingness to take it on."

What does future hold?

There are plenty of doom-mongers, but Enrique Krauze is not one of them.

He points to the fact that Mexico has changed a great deal in the past few decades, especially economically.

"If we have managed to change that in Mexico, now comes the difficult stuff - building institutions that can combat impunity, violence, injustice and corruption," he says.

Ms Dresser agrees on the issue of impunity - but for her, legalisation of drugs is central to any change.

"The approach should be centred on building what this country has never had - which is the rule of law," she says.

"Mexico's efforts to take on drug traffickers at this point are futile and the efforts are misguided."

BBC Mundo's Juan Paullier and Alberto Najar contributed to this report.

- Published27 September 2015

- Published7 September 2015

- Published27 February 2015