Guatemala families struggle for food in Central American drought

- Published

A drought in Central America has damaged crops and is threatening the livelihoods of as many as two million people.

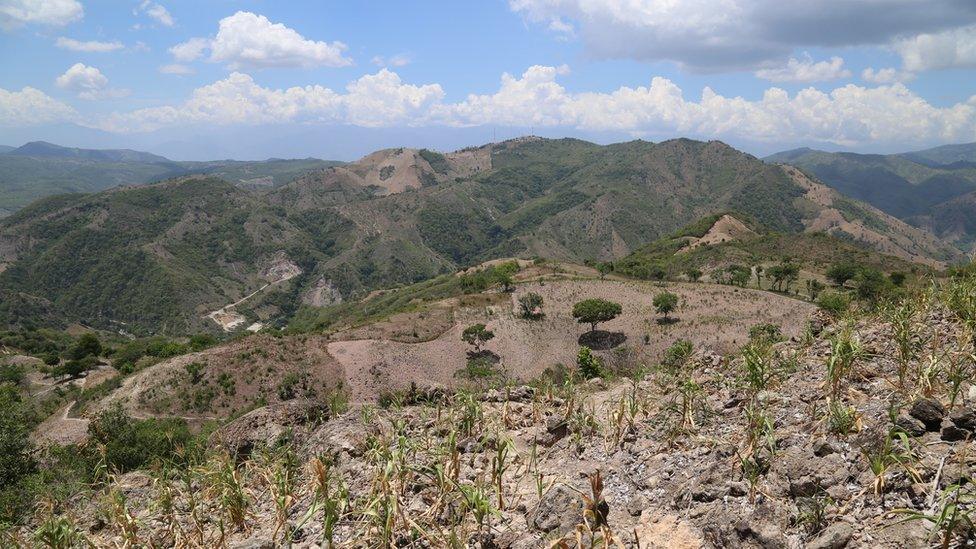

For hundreds of thousands of farmers in Guatemala, this year's harvest is over before it has even begun. The fields in the east of the country are yellow, the ground bone-dry.

For 74-year-old Marco Tulio Lopez Diaz, the situation is getting desperate. He has worked on his land in the village of San Miguel near Chiquimula his whole life.

It is a four-hour drive from the capital.

Farming is all that he knows, but with 80% of his corn crops dead and the ones that have survived providing no grain, he is hugely worried.

Marco Tulio lives in what is known as the Dry Corridor.

It is a drought-prone area of Central America that runs across El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua.

"We've often had tough droughts but not like this year," he says.

"We sowed the seeds, the plants are here but they've not produced anything. This year we've not been able to harvest."

Struggling smallholders

People in this part of Guatemala are smallholders who grow corn and beans.

Farmers go for weeks without any rain

They cultivate enough to provide food for their families.

In a good year, they can grow surplus to sell or store, but after several difficult seasons, they have run out of stocks.

According to Action against Hunger, four out of the last six years have seen below-average rainfall.

Government data shows that by July this year, 400mm of rain had fallen in the area of Chiquimula - that is half of what it would be normally.

Other parts of the Dry Corridor have received even less rain.

Farmers now go for weeks without any rain at all, which is damaging during the crucial crop-growing period.

Then, when it does rain, it often comes with such force that the parched earth cannot soak it all up and the crops drown.

The impact of El Nino

Many experts blame the change in weather patterns on El Nino.

Meteorologist Matt Taylor explains what El Nino is

Last year Guatemala, along with other Central American governments, declared a state of emergency because of the drought.

The problem is not expected to get any better any time soon.

The drought comes on top of the recent coffee-rust crisis which has swept through the region's coffee-growing communities.

Crop yields have fallen and that has led to unemployment.

Mr Tulio says the younger generations are increasingly heading to local towns to work - anything to avoid going into agriculture.

"This is a large area of impact and so people have two choices," says Diego Recalde who represents the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Guatemala.

"They look for other jobs in more urban areas in each of these countries or migrate through Mexico to the US."

In Guatemala, it is estimated that about 900,000 people have been hit by the drought in the Dry Corridor.

According to Maria Bernardez who is a food expert for the European Commission Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Office, more widely in Central America as many as 2.5 million people are affected.

No rain, no food

The drought is having an impact on people's health.

Doctor Juan Manuel Mejia works at the Nutritional Recovery Centre in the nearby town of Jocotan.

He is performing a check-up on four-year-old Claudia.

Dr Juan Manuel Mejia says some families are running out of food

Doctors say the drought is causing children such as Claudia, four, to suffer malnutrition

When she was admitted to the nutrition centre where Dr Mejia works, Claudia was suffering from Kwashiorkor, a form of severe protein-energy malnutrition.

Her body had swollen so much she could not open her eyes and her hair was falling out.

In the first two weeks at the nutrition centre her swelling has come down, which has seen her lose more than 6lb (2.7kg).

Her hair is also growing back.

"I've been working here 11 years and the reasons for malnutrition have always been lack of education, bad housing conditions, lack of drinking water, sanitary conditions," Dr Mejia says.

"Since last year, we've seen that some families come here malnourished because of a lack of food. I'm used to seeing malnutrition but there were always beans and tortillas at home - in the last few months, families have come and there are no tortillas or beans."

More support needed

Back in San Miguel, Justo Rufino Diaz, who is the president of the community development council, says the government is helping, for which they are grateful, but it is not enough.

The drought is affecting Central America's "Dry Corridor" covering parts of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua

"We get food every two months but we need to eat day to day. We want to work but there's nowhere to work," he says.

"When it's a good year and it rains, we can still harvest a bit. But we can't even grow to eat, let alone sell."

Mr Recalde says food aid is important but longer-term issues need to be addressed.

"With proper investments, with proper policies, that could change this reality and provide technology which is within reach of this country," he says.

"Water is produced massively in Guatemala and it all goes to the Caribbean or Pacific or Mexican borders - to all the rivers. The investment you need to make in this country to retain that water and to transform these areas is not there yet."

The FAO says investment is needed to help Guatemala retain its water

For Mr Tulio, it is the short-term that worries him.

Feeding his grandchildren is a priority. Then he can think about the future.

He wants a better life for them but it is a life that for now, he cannot provide.

- Published1 September 2015