Argentina election: Kirchner era draws to a close

- Published

Twelve years of the Kirchner era are due to come to an end on 10 December

Whatever the result of Sunday's run-off election in Argentina, it represents the end of an era.

President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner has served two consecutive terms and under Argentina's constitution is barred from running again until 2019.

The swearing-in ceremony on 10 December of whoever gets elected as the new president will officially mark the end of 12 years of Kirchnerism, the political movement named after President Fernandez de Kirchner and her late husband and predecessor in office, Nestor Kirchner.

Irene Caselli looks at some of the policies that left a mark on the country and which have divided voters.

Universal Child Allowance

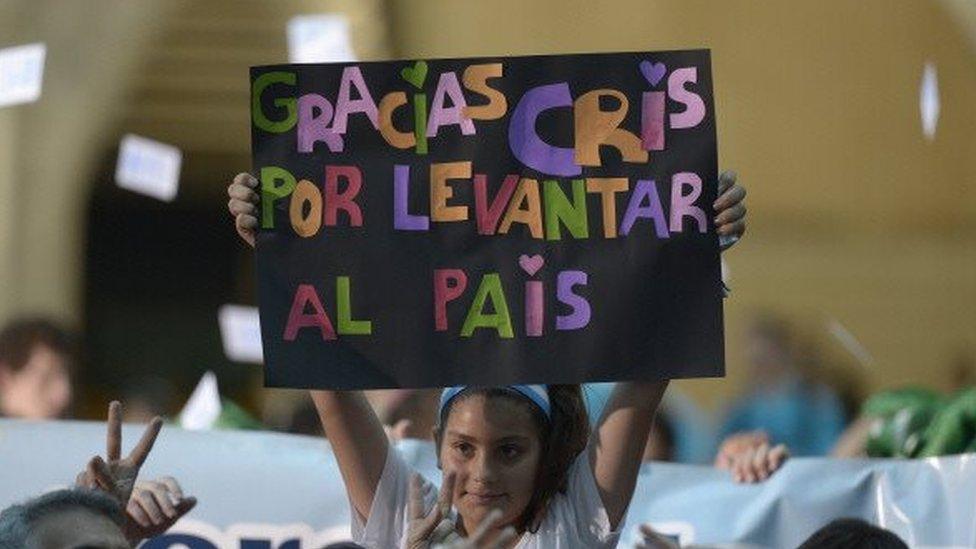

The universal child allowance has received broad support

Passed in 2009, the universal child allowance is arguably the most widely accepted social policy in Argentina.

It provides financial support to parents who are unemployed or work in the informal sector.

Parents receive a monthly stipend for each child under the age of 18 for up to five children.

They receive 837 Argentine pesos ($88, £57 at the official market exchange rate) per child per month.

Eighty percent of that sum is handed to them on a monthly basis, while the remaining 20% are retained until the start of the school year in March, when parents have to produce school attendance certificates and vaccination records in order to receive the outstanding amount.

The scheme has been praised by supporters and opponents of the president alike although its long-term effects on health, education and poverty remain to be determined.

Debt restructuring

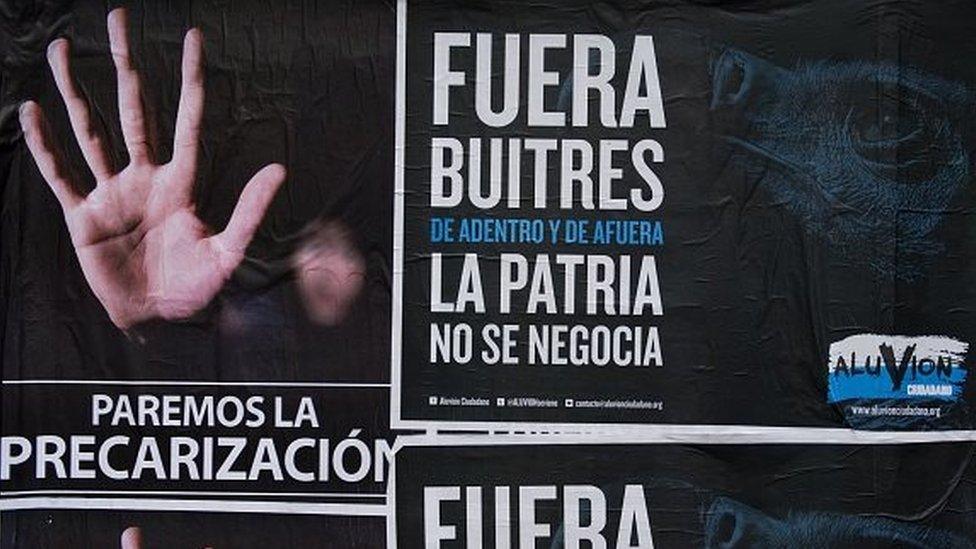

Argentina calls the hold-outs "vulture funds"

When Nestor Kirchner came into office in 2003, Argentina was facing a deep economic crisis.

The country was still reeling from its $100bn default - at the time the biggest sovereign debt default in history.

He began a process of restructuring the debt that had been defaulted on.

In 2005, a majority of creditors agreed to swap their bonds for new ones that left them with little more than 30 cents on the dollar.

A second debt restructuring in 2010 brought the percentage of renegotiated bonds to 93%.

The remaining 7% refused a deal and became known as the holdouts.

While even critics of Kirchnerism recognise the importance of the debt restructuring deals, some bemoan the government's failure to settle the long-running $1.3bn dispute with the holdouts, which has locked Argentina out of capital markets for a decade.

Read also: Argentina in denial over debt dispute

Inflation and soaring black market rates

The Argentine government has imposed currency controls to prevent capital flight

The opposition blames the Kirchners for rising inflation, lowering purchasing power and stagnant growth.

Since Argentina is cut off from borrowing on international capital markets, the government imposed strict currency and capital controls to avoid capital flight.

The amount of dollars available at the official rate is limited but demand remains high, leading to a soaring black market and an overvalued currency.

Government officials estimated that inflation would hit 14.4% this year, but independent economist predicted almost double that: 25% annually.

As inflation rises, the peso has increasingly less purchasing power.

The price of some basic goods has been stabilised thanks to an agreement between the national government and local businesses.

But critics say this only distorts the economy further.

The justice system

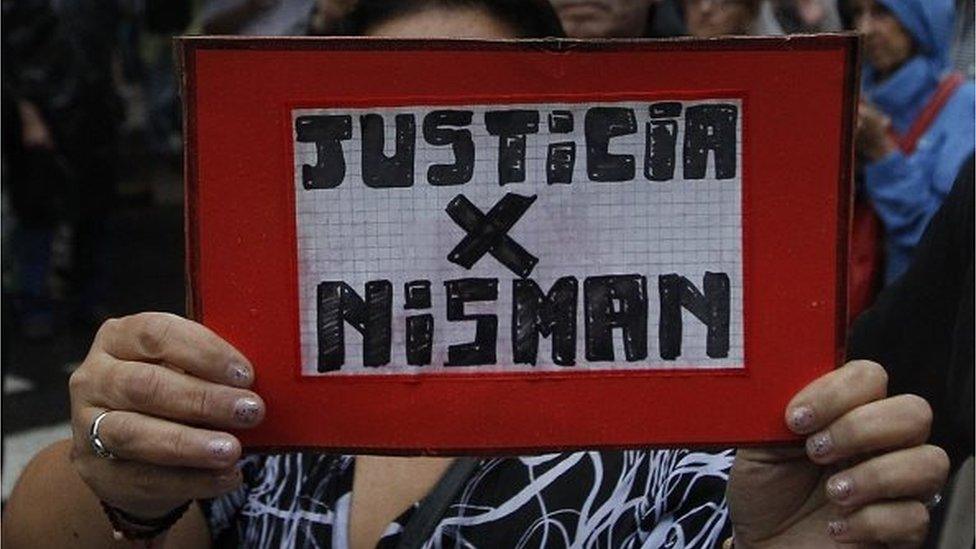

The death of prosecutor Alberto Nisman under suspicious circumstances rocked the country

When it comes to the justice system, the Kirchners' legacy is highly divisive.

Supporters highlight the government's decision to overturn amnesty laws which protected lower-ranking members of the military from prosecution for crimes committed during Argentina's military rule from 1976 to 1983.

One thousand former members of the military have been charged thanks to this change in the law.

But critics accuse the Kirchners of co-opting the justice system, slowing down and obstructing any investigation that could affect the government, from corruption charges involving Vice-President Amado Boudou to the death in mysterious circumstance of prosecutor Alberto Nisman, external.

Re-nationalisations

![Employees of Aerolineas Argentinas airline wait in front of the Congress building where senators prepare to turn into law a project to nationalize Aerolineas Argentinas. The sign reads, 'We are all Aerolineas [Argentinas].'](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/976/cpsprodpb/1466/production/_86222250_e0da1229-d861-4eae-84c1-d10d48093d08.jpg)

Over the past 12 years, the Kirchners re-nationalised many companies which had been privatised during the 1990s.

Argentina's postal service, its radio spectrum and Buenos Aires's water company were nationalised early on under Nestor Kirchner.

Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner drove the re-nationalisation of arguably the four most important companies: national carrier Aerolineas Argentinas, oil company YPF, Argentina's railway system and its pension fund.

While some celebrate these as an important reassertion of state control in the economy, critics complain of inefficiency and of government interference.

Same-sex marriage

Argentina has allowed same-sex marriage but abortion remains strictly limited

In 2010, Argentina became the first Latin American country to allow same-sex marriage.

The law gave gay people the same marital rights as heterosexuals, including adoption and inheritance rights.

In 2012, parliament approved a "gender identity law", which allowed for changes to be made to people's gender, image, or birth name on civil registries.

However, discrimination and violence against transgender people remains high.

Three transgender people have been killed in recent weeks.

Left-wing critics say the government has not been progressive enough to legalise abortion or the sale and consumption of marijuana, as neighbouring Uruguay has.

- Published15 October 2015

- Published28 September 2015

- Published31 July 2014