Patricia hits Mexico: Key questions and answers

- Published

Authorities warn the torrential rains associated with the storm may yet bring flash flooding and landslides

The strongest hurricane recorded in the western hemisphere - Hurricane Patricia - has made landfall on the Mexican coast, and is moving inland.

It has weakened, and has not so far wreaked damage to the extent initially feared, but is bringing torrential rain which authorities caution could trigger deadly floods and landslides.

Here is what you need to know about the powerful storm system.

How dangerous is it?

At its peak, Hurricane Patricia was a very rare Category Five hurricane, by definition the strongest, with winds of 325km/h (200mph).

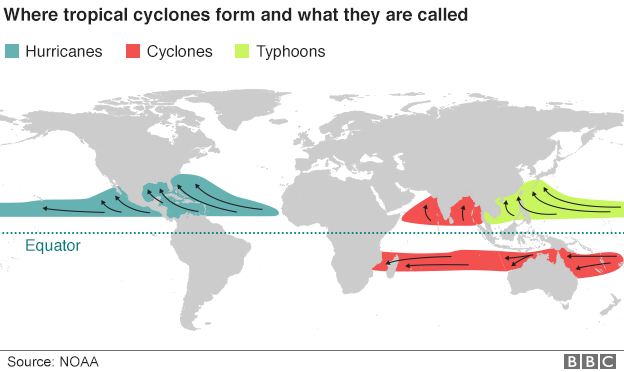

The US National Hurricane Center (NHC) warned it could be like a "nuclear detonation", and comparisons were drawn with Typhoon Haiyan - another Category Five event which devastated parts of the Philippines in 2013 and is thought to have killed more than 6,000 people - most through tsunami-like storm surges.

The hurricane weakened as it made landfall and is now a tropical depression - but authorities caution that "we cannot let our guard down".

The storm brings heavy rain - possibly reaching 50cm (20in) in isolated spots - which the NHC says is "likely to produce life-threatening flash floods and mudslides".

Why was it so powerful?

Forecasters were taken aback by Hurricane Patricia, which developed from a tropical storm into a dangerous hurricane in the space of 24 hours.

Local conditions were ideal for hurricane development - warm sea surfaces, little interaction with land and favourably light wind conditions.

But it is not clear exactly why it developed so quickly and this is likely to be closely investigated in the future.

One possibility may be higher sea surface temperatures due to the El Nino weather phenomenon.

This Pacific hurricane season has been the most active on record, with 15 to date, but experts caution about linking El Nino to specific events.

How was it measured?

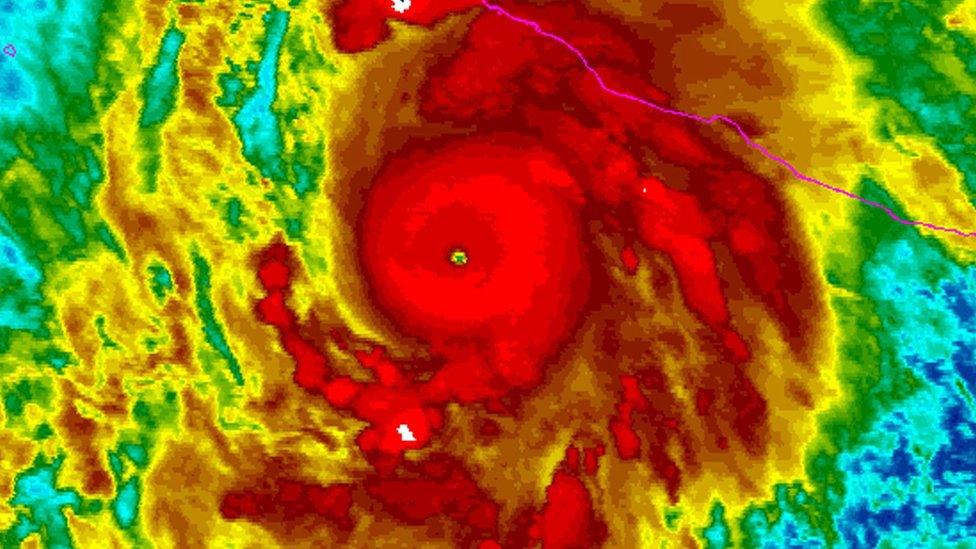

Forecasters described the possible impact of Patricia in apocalyptic terms

Routine aerial inspections picked up extraordinary weather conditions in the early hours of Thursday.

Meteorologists use the Saffir-Simpson scale, external to categorise hurricanes according to their sustained wind speed - long-lasting gales rather than sharp gusts, which can be even stronger.

Under the system, named after its inventors at the NHC, a Category One hurricane has winds from 74-95mph (119-153km/h), while a Category Five has anything above 157mph (252km/h).

But even the lowest category is dangerous, capable of dislodging debris and killing people, while Hurricane Patricia was in the strongest category.

"If we had a Category Six it would fit in there," said Stav Danos from the BBC's weather centre.

What damage could it cause?

Thankfully it appears that the hurricane did not hit populous areas with the ferocious winds feared - which officials had cautioned could toss cars in the air and destroy homes.

The main risk remains heavy rain and the associated risks of landslides and flash flooding, along with storm surges along the coast.

Some 400,000 people live in vulnerable areas, according to Mexico's National Disaster Fund.

Mexican geography may help dissipate the storm as it crosses mountainous regions - though these areas are particularly vulnerable to landslides and flash floods.

As it travels north, Hurricane Patricia could reach the US state of Texas where areas are already on flash flood watch.

How well prepared is Mexico?

Coastal areas are bracing themselves for tsunami-like surges

Mexico is no stranger to extreme weather, having to deal with tropical storms from the Pacific and Atlantic, sometimes simultaneously.

President Enrique Pena Nieto said Mexico had been "involved and very attentive" in the build up to the event, and had taken preventative measures including making shelters available for thousands of people.

Three Mexican states in the hurricane's path declared a state of emergency. Schools were closed and shops boarded up.

Thousands of people, including tourists, were evacuated but some have now left shelters, despite the government urging people to stay while the storm remains a threat.