Mexican marijuana activists on a high after Supreme Court ruling

- Published

Armando Santacruz is an unlikely poster boy for pot-smoking. He is a prominent businessman with a chemicals company listed on the Mexican stock exchange, but is just as comfortable lining up international trade deals as he is about weighing up the pros and cons of Mexico's marijuana market.

While Mexico has been fighting its war on drugs in recent years, clamping down on cartel activity in an effort to stem the trade north to the US, Santacruz has been fighting a parallel battle.

When he is not in the boardroom, he spends his time working with Mexico Unido Contra la Delincuencia (Mexico United Against Crime), a non-governmental organisation working to improve security and justice in the country. It also, controversially, argues for the legalisation of marijuana.

Santacruz points out that about 60% of the people in federal prisons in Mexico are serving time for drug crimes. Of those, some 60% are in for marijuana offences with the rest there for crimes relating to other drugs.

If marijuana was legalised, there would be far fewer people locked up in an environment that often just fuels crime instead of solving it.

Too much money and effort is spent on chasing after small drug users, says Santacruz. Mexico has far bigger problems on its hands and time would be better spent focusing on tackling extortion, kidnap and rape.

Cannabis club

Along with three other activists, Santacruz formed a small club called the Mexican Society for Responsible and Tolerant Personal Use (SMART, in Spanish). They began their campaign in 2013, seeking permission to grow plants for recreational use.

Armando Santacruz (centre) has spearheaded the SMART campaign

The argument they used in the Supreme Court battle was based on human rights and freedom of choice. And it was an argument that obviously convinced the Supreme Court - on Wednesday, it voted 4-1 that prohibiting people from growing the drug for consumption was unconstitutional.

Santacruz was more pragmatic, seeing the vote as "historic" and looking to the future.

"Congress in this country can no longer ignore that this is happening and that it doesn't have to do anything," he told me after the vote. "Congress will have to address the problem because you can't have laws that are unconstitutional and at the same time not do anything about it."

The ruling though does not mean that marijuana is now legal. It simply means that the four plaintiffs who brought the case are able to grow and smoke their own marijuana.

In order for any law to be changed, the Supreme Court would first have to vote in favour four more times on a similar case. But experts see this as the first step in what could lead to the legalisation of the drug.

Anyone who wants to use the same criteria to ask for the same rights now has a precedent. Santacruz also foresees possible class action lawsuits, which would bring thousands of people to demand the same rights.

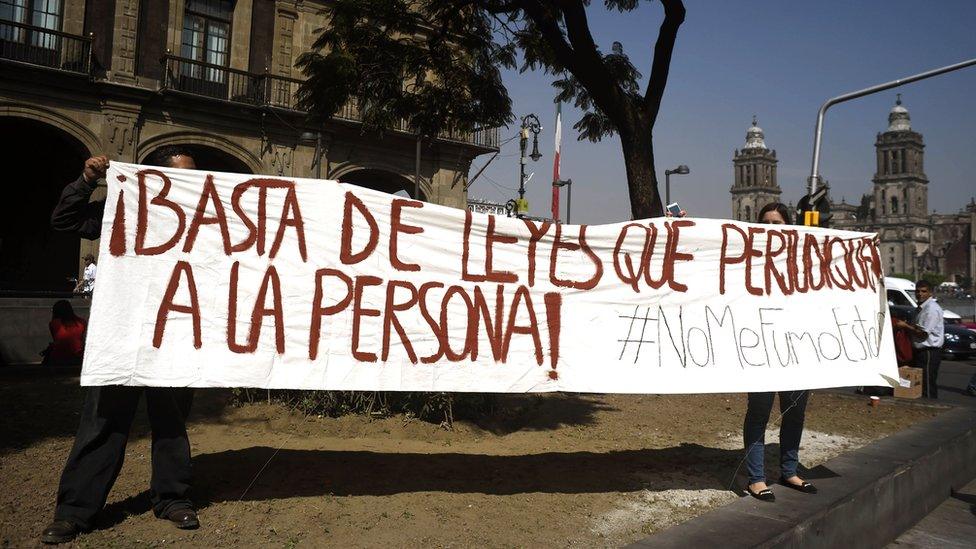

There were celebrations outside the Supreme Court on Wednesday. The signs read: "#Self-cultivation yes, #Cannabis uncensored"

Liberalisation fears

In a country ravaged by drug violence that has killed an estimated 100,000 people since 2006, the ruling sits awkwardly among some. There is a fear that liberalising drugs policy could lead to more violence.

"There is far less drug use in Mexico than in the US," says Dr David Shirk, director of the Justice in Mexico project at the University of San Diego. "There's also a more socially conservative outlook for drug use in Mexico and as much as it's a place for making and moving drugs, it's not been traditionally a place where drugs are widely consumed."

While more than 50% of people in the US believe that marijuana should be legalised, in Mexico a recent poll (in Spanish), external suggested that just 20% of people support legalisation while 77% oppose it.

There are plenty of people against the decriminalisation of marijuana. This banner reads "Enough of laws which are detrimental to people"

Marijuana in Mexico

Mexico has a relatively low marijuana usage rate - just 1.2% of the population smoke marijuana at least once a year, compared with 13.7% in the US

That is made up of 2.2% of men and 0.3% of women

Though usage may be low, illegal production and trafficking is a big problem and marijuana offences account for about 500,000 arrests a year

But Santacruz, who believes small-time drug trafficking generates violence in Mexico, is adamant that decriminalising marijuana would help reduce that violence.

"The struggles are directly proportional to the value of the [black] market [for drugs]," he says. "So with that market losing value, it can also decrease violence generated by the fight for those markets."

Lost profits

Much has been talked about the economic effects of legalisation and the impact on cartel activity. But with Mexico supplying so much to America, any laws that are passed in Mexico will only go so far in influencing the international market.

The Supreme Court's decision could set a legal precedent for future rulings concerning the use and sales of marijuana

"Much of the marijuana produced by the Mexican drug trafficking organisations is exported to the US," says Beau Kilmer, co-director at the RAND Drug Policy Research Center in California.

"If Mexico legalised marijuana production for domestic consumption and exports to the US remained illegal, there would still be incentives for organisations to smuggle marijuana to the US."

One thing everyone agrees on is that legalisation would reduce the profitability. As one expert put it, if everyone can become a small-time smuggler because they can grow marijuana, cartels will have to start competing with Joe Bloggs off the street.

"Cartels will stop growing marijuana bit by bit and they'll concentrate on growing heroin, as is happening in Guerrero," says Raul Benitez-Manaut of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. "That means that violence will continue."

Never mind the arguments against, the activists who have been campaigning for changes can be happy with Wednesday's result.

Santacruz likens the vote to placing a wedge in a small crack.

"The hardest thing was to create that crack and that's been done."

- Published4 November 2015

- Published20 November 2012