Kon-Tiki2: Why would you cross the Pacific on a wooden raft?

- Published

There are crew members from Norway, Sweden, Russia, the UK, Peru, Chile, Mexico, Canada and New Zealand

This is a story about survival, science and exploration. But it is also one about a struggle against the odds, just as it was on the first voyage back in 1947.

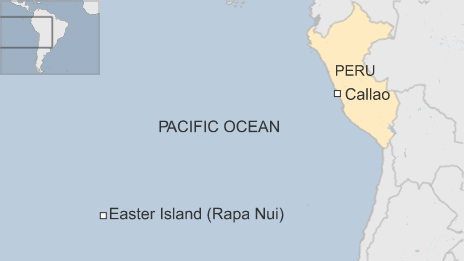

Norwegian historian Torgeir Higraff, 42, and a crew of 13 people have just left the Peruvian port of Callao and embarked on one such adventure.

He wants to cross the Pacific Ocean from Peru to Easter Island, at the eastern tip of Polynesia - and then back.

This Kon-Tiki expedition goes further than two previous trips. The crew will aim to complete a 5,500Nm (10,000km, 6,200-mile) round trip, despite most naval experts saying it is impossible.

Especially when you are travelling in two wooden rafts that are each 17m long, 7m wide and 40cm deep (56ft x 23ft x 1ft 4in).

Historian and expedition leader Torgeir Higraff believes the Inca empire established regular links with Polynesia

On their way to Easter Island, or Rapa-Nui, they will follow the gentle currents and winds of the ocean. But on the way back, "we will be sailing in rough waters", says Higraff.

The winds at sea can easily reach speeds of 20 metres per second, with waves as high as 10m (30ft), he says.

This makes fishing almost impossible, explains Pal Borresen, CEO of the expedition.

So they are carrying plenty of dry food.

And high hopes.

Supplies

Each raft will carry:

2,500 litres (550 gallons) of water

100kg (220kg) of oranges

200kg of rice

80kg of lentils

When Higraff's fellow Norwegian Thor Heyerdahl, external, considered one of the great adventurers of the 20th Century, made the first voyage in 1947, it was also against the odds.

Almost 70 years ago, nobody thought it possible to travel by raft from Peru to Polynesia. The academic world was particularly dismissive of the suggestion.

Ancient Peruvians, they thought, did not have the knowledge to do it.

Heyerdahl proved them wrong.

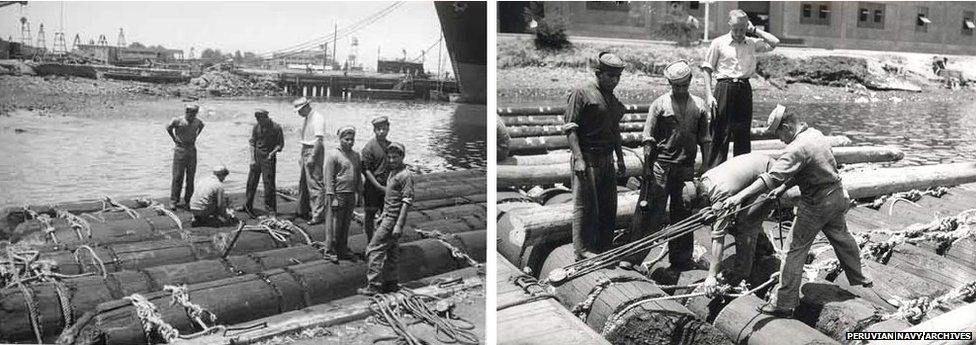

The Kon-Tiki raft from the 1947 expedition was made from balsa tree trunks

In 2006 Higraff led his own expedition, on the Tangaroa raft.

At the time, experts said he would not go any faster than Heyerdahl did in 1947 because the rafts were just following winds and currents.

Higraff and the Tangaroa broke Heyerdahl's record by 30 days.

The rafts are made of balsa wood, a tree species lighter than cork and native to the Americas.

Balsa takes about five years to reach its full height of 20m to 25m.

Expedition leader Torgeir Higraff picked the tree trunks he wanted for his raft

For this trip Higraff chose the 44 trees he needed and shipped them from Ecuador - which has 90% of the world's balsa supply - to Callao, where a team of 30 people built the rafts in three weeks.

As a historian, Higraff had read the Spanish chroniclers who wrote about the seafaring activities of Inca emperor Tupac Yupanqui (ca. 1440-1490), who is believed to have visited Mangareva and Easter islands in the 15th Century.

"They did have the technology," he says. And he believes that regular ties had existed between South America and Polynesia for hundreds of years before the arrival of the Europeans.

"This will be the first time in the modern era that a round trip will be made."

Expedition scientist Dr Cecilie Mauritzen is using the trip to study changes in the ocean

"The oceans are changing very fast and nobody is paying attention," says Dr Cecilie Mauritzen, an oceanographer who is the expedition's chief scientist.

"This is a chance to give oceans a voice."

Dr Mauritzen's work on the trip will focus on climate change, pollution from microplastics and the impact of the El Nino weather effect.

"The seas are also becoming more acidic, warmer and getting less oxygen," she explains. If oceans take 90% of the extra heat that humans produce, "they are protecting us for the time being - but for how much longer?"

To help the scientific work, the rafts have been fitted with top-notch transponders, beacons and satellite communications, courtesy of Norwegian technology companies.

The crew will be living in close quarters during the voyage

Of the 14 people making the crossing, only two have sailed in similar rafts before. Many of them have not even sailed at all.

"But each has been carefully chosen for their skills, and we have also taken gender and age into account", expedition CEO Pal Borresen says. The crew are between 19 and 64 years old.

That makes for a very diverse group but not necessarily an experienced one. One of the biggest challenges during a trip like this is how to bind the group and keep spirits up.

Prepared and focused

"I have to be there for them and make them perform at their best," Torgeir Higraff says. He reckons there will be moments of anxiety and fear, but believes he will be able to deal with those.

What is less predictable are accidents. There will be a Russian doctor on board. If something worse should happen, the Peruvian and Chilean navies will be following them closely from the coast and a Norwegian rescue centre will keep track via satellite.

But aside from these contingencies, Torgeir Higraff is sailing with one thing in mind.

To prove to the world that a round trip is possible, on a raft and with 15th Century technology.

You can follow the expedition's progress on its website, external.

- Published28 February 2013

- Published6 September 2012