What does Argentina’s election mean for South America?

- Published

Macri supporters are hopeful of change

In the future, books about Argentina's economic history in the early 21st Century will have to come with a comprehensive glossary.

South America's second-largest economy has been through so many different economic policies and experiments in the past two decades that a whole new vocabulary has sprung up to explain day-to-day economic transactions.

Buenos Aires' main commercial street, Calle Florida, now has dozens of "little trees" (arbolitos), the name given to black-market traders who buy and sell dollars openly in the streets. They stand around like bushes holding up their green leaves (dollar bills).

Some traders prefer to "make puree" ("hacer puré"), which is to buy dollars from the government and resell them to the "caves" ("cuevas"), the illegal exchange rate shops that deal with "blue" (black-market dollars).

This dynamic jargon is a reflex of a country that has been through a sort of economic rollercoaster ride for the past 15 years.

In 2001, the country had plunged into chaos - politically volatile, financially bankrupt and with violence erupting in the streets. It famously had three different presidents in two weeks.

By the second half of the decade, however, it was one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, on the back of soaring global commodity prices and a partly successful debt-restructuring plan. By 2005 it had surpassed its pre-crisis level, external.

Argentina presidential election 2015:

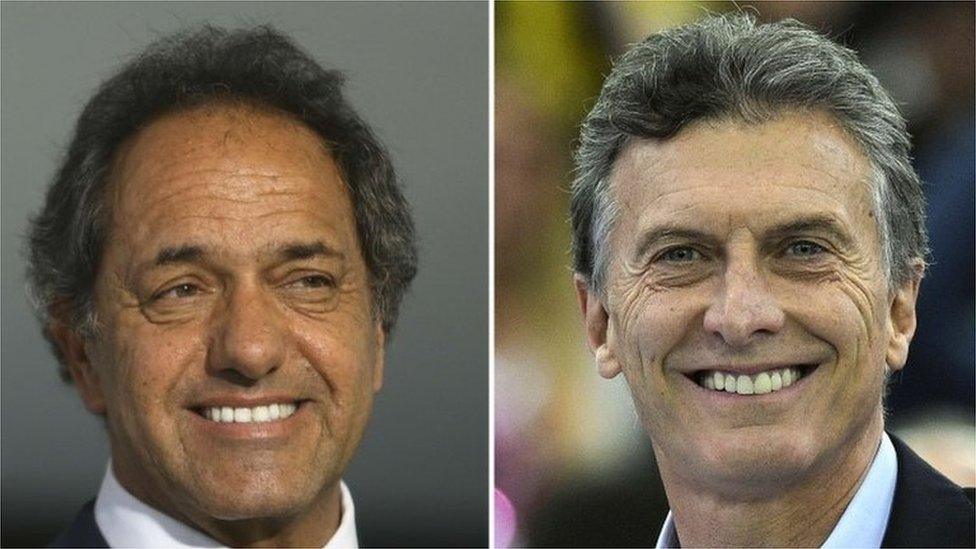

Wyre Davies reports that there was surprise in the Scioli camp that the result was so close

Argentines are voting for their next president, as Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner stands down after eight years in power.

Her hand-picked successor, left-winger Daniel Scioli, was leading in the polls and had been expected to win comfortably.

However, the first round of voting failed to produce a winner, as Scioli was pushed very close by Mauricio Macri, the centre-right mayor of Buenos Aires.

To win outright in the first round, a candidate needed 45% of the vote or a minimum of 40% as well as a 10-point lead over the nearest rival.

The run-off on 22 November will be the first time an Argentine election will be decided by a second round.

But now, since 2011, Argentina is in deep economic trouble again, external, with weak growth, rising unemployment and high inflation.

Next week's presidential election - between government-backed Daniel Scioli and the opposition's Mauricio Macri - will be a chance for Argentines to chose which path to take in order to solve the current economic woes.

It will also be closely watched by South American neighbours such as Brazil and Venezuela, who are themselves at a crossroads, grappling for political answers in the face of economic storms.

Red tape

Many of Argentina's more immediate economic problems are down to the government's exchange rate policy known as The Clamp (El Cepo), a series of measures adopted in 2011 intended to stem the flow of capital that began leaving the country.

Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner has been president since 2007

It did contain the tides to some extent, but it created far greater problems domestically.

Buying dollars officially under the Cepo is a nightmare of red tape; buying them in the black market is prohibitively expensive. The costs for importing soared and were passed on to consumers, which made inflation shoot through the roof.

Under high inflation, many of Argentina's conquests in the past decade are beginning to be undone. Growth stalled at first, and there is now a threat of it entering reverse mode.

After including millions of people in the welfare system, Argentina stopped releasing poverty figures last year, a hint that those worse off are not seeing their lives improve.

El Cepo:

Series of measures taken by Argentina to contain outflow of capital

Started in November 2011

Argentines wanting to buy dollars had to get an official permit from the government

Dollars are officially bought via the website of the AFIP, a body linked to the finance ministry

It created a black market, the official dollar is sold at about 9.50 pesos for those who are approved by the AFIP; unofficially it costs around 15 pesos

It increased inflation in Argentina and created barriers to trade

Under the Kirchner family - first Nestor in 2003 and then Cristina Fernandez since 2007 - the government increased its presence in many sectors, from social programmes to nationalisation of private firms.

Now with cash-flow problems and low reserves, the government is in desperate need of revenues, but it is still virtually excluded from international bond markets, after it defaulted on its debt in 2001.

Change promised

Argentines have been promised change by both presidential candidates.

Both Scioli and Macri agree that Argentina needs to open up its economy to the world again, by phasing out The Clamp, facilitating trade, re-entering bond markets and having a less controlled currency.

But the speed and the details of change vary according to the candidate.

Most expect Macri to change the economy more drastically, while Scioli's adjustments would come at a slower pace.

Daniel Scioli is the government-backed candidate - and was expected to become president

More importantly there is a highly symbolic element to this election that is likely to have repercussions in the whole of South America, even though its economic problems are very distinct.

The region's politics have followed great ideological waves in the past decades.

In the 1980s and 1990s, countries such as Brazil, Argentina and Venezuela elected governments that followed the so-called Washington Consensus - a series of doctrines that included privatising state-owned companies and reducing the presence of the state in the economy.

In the 2000s, most South American countries - including Paraguay, Ecuador, Bolivia and Uruguay - moved sharply towards the left, choosing governments that prioritised state-led investment and social programmes for the poor.

Crossroads

Now Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela are all facing tumultuous times in their politics and economics, and are again at a crossroads.

If Argentina elects Daniel Scioli on Sunday, it will be a way to give some validation to the Kirchner era that defined the country for the past 12 years.

Similarly, a Macri win would mean a rejection of that legacy and a return to more market-oriented policies.

Two weeks later, under great economic and social tension, Venezuelans will go to the polls in parliamentary elections, which are likely to be the toughest challenge, external for Nicolas Maduro, the successor to the late Hugo Chavez.

Nicolas Maduro faces a tough challenge in Venezuela

Venezuela has been implementing a "Bolivarian revolution" since 1999, with a strong presence of the state in all parts of the economy.

But with low oil prices and chronic shortages, its economy is now at its most fragile stage in over a decade.

Meanwhile, Brazil - which has just been through a similar test when it re-elected President Dilma Rousseff last year - is facing political turmoil amid a large-scale corruption scandal, as the opposition is pushing for her impeachment, external less than a year after she took office again.

At the same time, Rousseff is adopting economic measures to counter the country's crisis that are closer to the market-oriented policies preached by her opponent in last year's election, Aecio Neves.

Dilma Rousseff is facing calls for her impeachment

Brazil's political future is still uncertain, as no-one knows whether the impeachment movement can be successful.

But Rousseff and the Workers' Party are facing a difficult test to keep the policies set by former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva from 2003.

With so many question marks in voters' minds across the region, South Americans will be watching closely what happens to Argentina's politics and economy after Sunday, under a new president.

- Published26 October 2015

- Published11 July 2011

- Published8 October 2015

- Published12 November 2015