Forced sterilisation haunts Peruvian women decades on

- Published

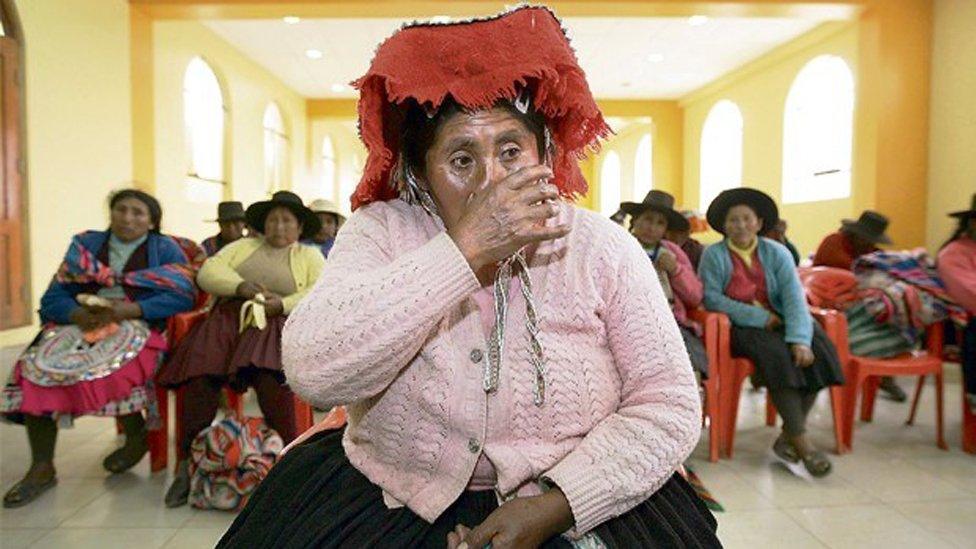

Sabina Huillca is one of the women who was forcibly sterilised in Peru

Sabina Huillca, 46, sells bread on the streets of Lima.

Twenty years ago she was growing potatoes and corn and bringing up her children in her native Huayllacocha, a village in the Andes four hours by car from the provincial capital, Cuzco.

But she told me her life changed forever one day in 1996.

A doctor suggested Ms Huillca, who was heavily pregnant at the time, visit a health clinic in the town of Izcuchaca.

'Nightmare'

She told the BBC that the nightmare started straight after she gave birth.

Most of the victims were poor indigenous women

"A nurse put me on a stretcher and tied my hands and feet," she recalled.

"I asked them to bring me my little baby girl but instead they anesthetised me," she said.

"When I woke up, the doctor was stitching my stomach. I started screaming, I knew I had been sterilised."

Ms Huillca was a victim of a family planning programme as a result of which thousands of women were forcibly sterilised.

The programme, launched in 1996 by then-president Alberto Fujimori - who argued that a lower birth rate would drive down poverty - at first received much praise.

But then more and more women complained about being sterilised without their consent.

Most of them were poor, indigenous and spoke Quechua.

Deadly consequences

Over the years, their voices became louder and clearer.

Some of the women have given testimony to the official enquiries

The first case to be investigated was that of Mamerita Mestanza.

The 33-year-old lived in Cajamarca, in the northern Andes, with her husband and seven children.

Timeline

1995: President Alberto Fujimori modifies the General Population Law to incorporate voluntary surgical contraception (sterilisation) as part of the contraceptive methods on offer

1996: Reproductive Health and Family Planning Programme starts and Mamerita Mestanza dies following a tubal ligation she did not consent to

2001: Inter-American Commission on Human Rights awards a settlement to her family, opening the door to other cases

2003: Prosecutors start investigating allegations of forced sterilisations

2009: Investigation shelved for lack of evidence

2011: Investigation is re-opened

2014: Second probe shelved for lack of evidence

2015: Investigation re-opened again, Peru's government creates a national registry of forced sterilisations

2016: Deadline for the investigation to conclude

According to testimony given by her husband, in 1996 she began coming under constant pressure from staff at her local health-centre to be sterilised.

She was even told that it was illegal to have more than five children and that she could be jailed for having any more.

She finally succumbed to the pressure and agreed to have the tubal ligation procedure in March 1998.

But her husband alleged that she was not given any information about the risks involved.

Eight days after she was sterilised, Ms Mestanza died of a post-operative infection which doctors had failed to treat.

Her husband said that he requested that his wife be given medical attention on a number of occasions and was refused.

One of many

Some of the victims have been speaking out and telling Peruvian media their stories.

The voices of the women who say they were forcibly sterilised are increasingly being heard

Esperanza Huayama said she was lured to a health clinic by promises of food, vitamins and medicine.

Health Ministry staff went from village to village and according to Ms Huayama, at least 100 women from her area went to the clinic on the same day as she did.

"I was three months pregnant and I didn't know it. But they [health centre staff] did and still they went ahead." she said.

"First they offered medicine and then they treated us like animals."

Micaela Flores said she and other women were taken by lorries to a health centre.

"We all arrived innocent and happy, then we heard screams and I just ran."

She said the doors were padlocked so she could not escape and that she was sterilised against her will.

Staggering numbers

According to data released in 2002 by Peru's Health Ministry, 260,874 women had tubal-ligation operations between 1996 and 2000.

More and more women have been coming forward to tell of their ordeal

Rights group the Latin American Committee on Women's Rights (Cladem) says that as few as 10% of them might have given consent.

They believe that the others were victims of forced sterilisations.

Thousands of women have reported being harassed, threatened or blackmailed to undergo the procedure.

As a result of their testimony, Peru's Ombudsman's office prepared three reports into the issue between 1997 and 2002.

They documented mistakes made during the sterilisation campaign and made a number of recommendations.

Key findings and recommendations by the Ombudsman's office

Women queued to give evidence at police stations in the affected areas

The office found a lack of guarantees for free choice and informed consent

No information offered about other contraceptive methods, campaign only promoted tubal ligation

Exertion of pressure and no time offered to consider their choice

Lack of post-operative follow-up treatment

The office recommended: Guarantee freedom of choice, informed consent and access to all forms of contraception

Replace all campaigns which exclusively promoted tubal ligation

Compensate all those sterilised without their consent

Urge the judiciary and officials to investigate all cases of forced sterilisation

Despite these reports, President Fujimori - who is serving a 25-year sentence for human rights abuses and corruption - has always maintained these procedures were consensual.

His daughter Keiko, a presidential candidate who polls suggest could win next year's election, was recently asked about the allegations.

She blamed individual rogue medical practitioners.

Doctors speak out

But new evidence contradicts her.

In October, Peruvian newspaper La Republica published an in-depth report into the scandal.

It quoted three doctors who said they had refused to follow orders to sterilise women in the 1990s.

One of them, Rogelio Martino, worked in a poor neighbourhood of Piura in northern Peru.

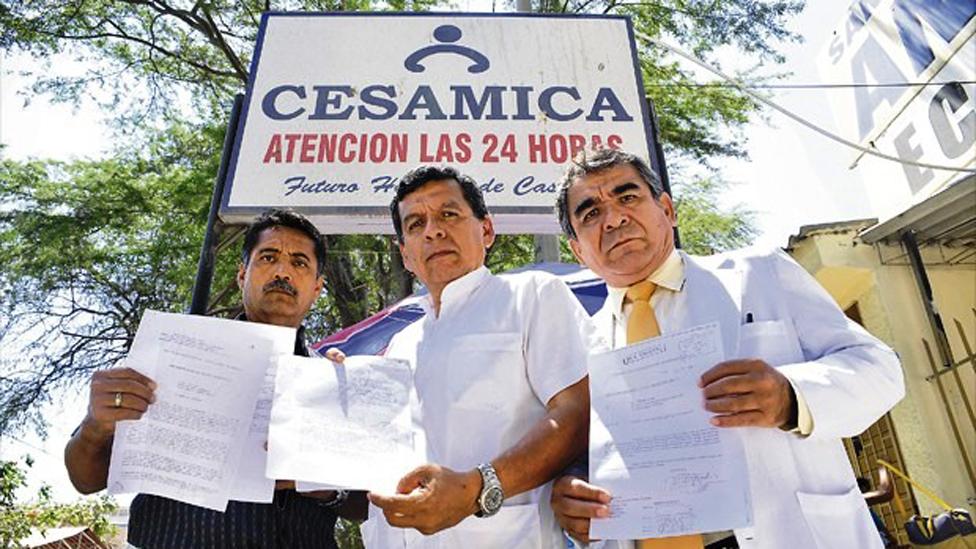

Dr Martino (centre) and some of his colleagues say they refused orders to sterilise women without their consent

According to Dr Martino, his team was told to sterilise at least 250 women over four days in July 1997,

He and his colleagues considered this highly risky, and an undignified way to treat poor women.

"We had no option but to report it to the local prosecutor's office," explains Dr Martino, who later resigned.

He said he had no doubt that the sterilisations were a state policy.

Ongoing struggle

In early November, the government ordered that the investigation into the sterilisation programme be reopened.

Victoria Vigo is one of the victims who has been campaigning for justice

As part of the probe, investigators set up a national registry of victims.

Sigfredo Florian is a lawyer who works with the Institute of Legal Defence, which has taken up a few of the cases.

He believes that the registry will help to determine the extent of the practice "because no-one knows how many victims there really are".

Maria Ysabel Cedano who leads women's rights group DEMUS welcomed the move but said that the women still had not had their rights restored.

Lawyer Sigfredo Florian thinks it is key to know the number of victims

Maria Ysabel Cedano (centre) says much more needs to be done

Prosecutors have been thwarted before, twice the case was dismissed before being re-opened this year.

While this most recent investigation should be wrapped up by February 2016, court proceedings are still a long way off.

Meanwhile, victim Sabina Huillca is still struggling with life since her forced sterilisation.

"At the beginning I just wanted to die but my four children kept me alive," she recalls.

She is currently living in Lima where she is receiving treatment for ovarian cancer, which she thinks is a result of the operation.

For her, it does not matter how long it takes to get justice: "I just don´t want this to happen to other women."