Venezuelan healthcare in collapse as economy ails

- Published

Hospitals have no medicine to treat leukaemia patients such as two-year-old Santiago Ortiz

Santiago Ortiz is lying, eyes closed, on the bed. He is no picture of repose.

Above his jaundiced, swollen belly, his thin chest is pumping fast. His face twists into the pillow. An oxygen mask is strapped tight across his mouth and nose.

Santiago is two years old and has acute myeloid leukaemia. What he does not have is adequate treatment.

Inside his cramped room, on the 10th floor of the University Hospital of Caracas, his doctor, paediatric resident Joam Andrade, points to the cockroaches on the walls, and the sticky tape holding his oxygen tube together.

But those are details. Santiago lacks medicine. "This is the third time since last year that he's relapsed and we've had to admit him," Dr Andrade says.

"All we can do is try to control the pain."

She writes in my notebook what she wants to prescribe, and cannot, because there is none in Venezuela: "Cladribine. 5-6 ampoules. 10mg."

Worst in the world

Plenty of countries have damaged or failing health systems. Few are like the Venezuelan.

This country, which holds parliamentary elections on Sunday, has oil reserves exceeding Saudi Arabia's, external.

That natural wealth provided hundreds of billions of dollars of export earnings for Hugo Chavez, the man who, for 14 years until his death in 2013, ushered in and then presided over a radical left Bolivarian Republic.

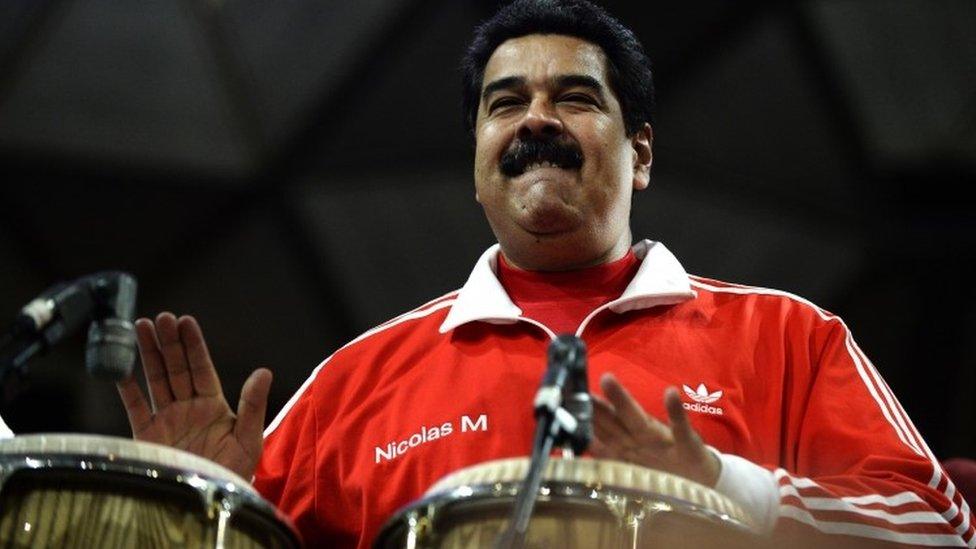

President Nicolas Maduro has presided over an economy where inflation has hit 159%

Under his successor, Nicolas Maduro's rule, though, the oil price has cratered. The IMF forecasts, external the country's economy will contract 10% this year, 6% next.

Those are the worst figures in the world, excluding Syria, and there's no data for Syria.

Actually, there's no official data from within Venezuela, because the Central Bank has stopped reporting its own economic figures.

So we have to rely on the IMF's estimate that inflation in Venezuela will be 159% this year and 204% next year. They are also the worst figures in the world.

And most Venezuelans will tell you they're a woeful underestimate.

It was against this wreckage, in a bare hospital lecture-room, that Dr Andrade joined a group of doctors, students and heads of department to talk to me about the state of the hospital.

I had asked to speak to one or two. Over the course of an hour, more than 15 - I lost count - walked in, off shifts, off ward-rounds.

They waited their turns and then listed their woes. No syringes. No operating equipment. Violence from patients' relatives, furious that the hospital management had assured them of high quality care.

The paediatric emergency department closed for repair; the temporary site had, one student doctor told me, "no oxygen, no medicine for asthma, no antibiotics, no food".

Opposition poll lead

The hospital administration declined to comment. But the government insists it still has a good story to tell.

Ernesto Villegas has just stepped down from two years as a minister, in order to compete in the elections as a candidate for the governing Chavista PSUV. It is, perhaps, a brave move, given the wide lead opinion polls are giving the opposition coalition.

Venezuela's woes

Former bus driver Nicolas Maduro won a disputed election in 2013 to succeed his mentor Hugo Chavez.

His poll ratings have slumped amid falling oil prices and accusations of mismanaging the economy.

Venezuela depends on oil for 96% of its foreign currency export earnings, external; the collapse in prices has severely limited the country's ability to pay for imports, causing shortages of basic household goods.

Unlike some other mineral rich states, Venezuela had no "rainy day" fund or contingency plan for falls in export income.

Mr Maduro has accused foreign powers and speculators of waging "economic war", external on Venezuela and said his policies are aimed at defending the spending power of ordinary Venezuelans.

The Organisation of American States (OAS) has expressed concern about the jailing or barring from the election of a number of opposition political figures.

Despite these setbacks, polls suggest the opposition could this month gain its first majority in the National Assembly for 16 years.

Seated against the railing of a park overlooking one of Caracas's working-class barrios, Mr Villegas, wearing a party-embossed blue shirt, said "perhaps in that hospital there are issues".

But the bigger point, he said, was the vast improvement in primary health care, particularly for the poorer sectors, such as the "23 de Enero" barrio, which loomed over his shoulder. "Today, thousands, millions of Venezuelans get healthcare, can exercise their right to healthcare."

But community health centres are no help, right now, for Yixember Cohen.

Mr Cohen: "It's just a timebomb. If I'm not treated, my heart will explode"

The 30-year-old graphic designer is standing by his bed in University Hospital. His eyes are bright, his tattoos plentiful.

Mr Cohen has Marfan syndrome, a genetic disorder that means his aorta is dilating dangerously. With a smile that's polite, apologetic and entirely incongruous, he explains his prognosis: "In my case, it's just a timebomb. If I'm not treated, my heart will explode. Pow! Plop!"

This bomb could be defused easily enough through surgery, and the use of a replacement, mechanical valve.

But one of his doctors, who asked not to be identified, said that in Mr Cohen's case, the surgeon could not operate without a complete set of valves, as he could not tell what size he would need.

"It's routine equipment. We've always had it," he told me, a few metres away from his patient. "But we haven't had a complete set for more than a year. I don't know when we'll be able to import any more. Management says the end of the year. I'm not sure I believe them."

Mr Cohen smiles warmly as we leave. "You have to remain strong when your life is on a knife-edge," he says. "And, in any case, it's not good for my heart, if I get upset."

'Not fair'

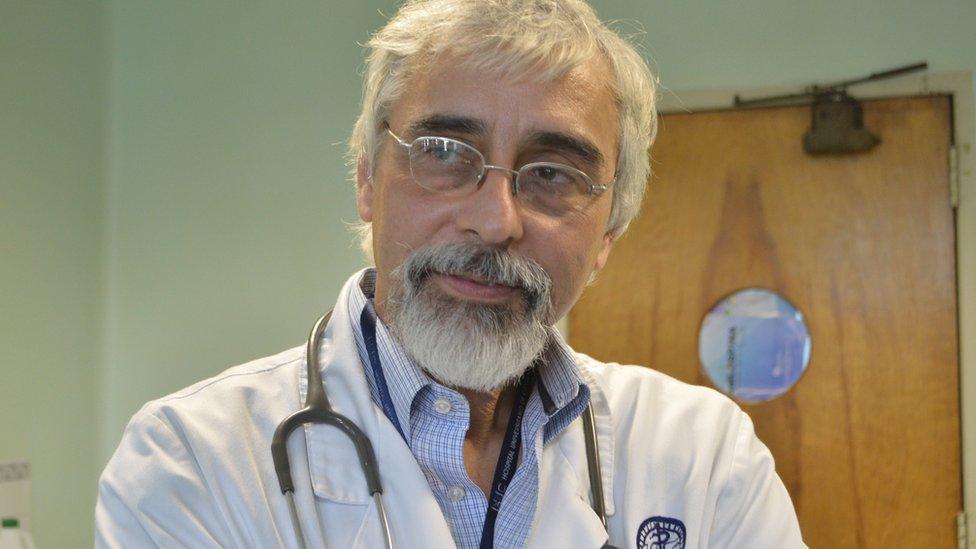

In contrast, Dr Ivan Machado says he "will not stay calm".

He has been treating patients at University Hospital for 35 years and is now head of cardiology and director of the medical school. His salary is about 20,000 bolivars a month.

To put that in context, according to the independent Venezuela-based research centre Cenda, the basic goods an average person needs for a month cost 100,000 bolivars.

Dr Ivan Machado: "It's not fair to make us just look at our patients, and see which way they are going to die"

But that is information Dr Machado imparts just as an aside. What matters to him is that his department has not been able to perform a single heart surgery in the past three weeks.

"We have gone from 450 open heart surgeries a year to 20. And from 1,200 cardiac catheterisations per year, it's now at most 300.

"I'm almost at the point where I have to say we need to close our department of cardiology, because it's not fair to make us just look at our patients, and see which way they are going to die."

He and his colleagues have looked for answers. The BBC has seen a letter sent in June, by Dr Machado and other heads of medical departments to the government ombudsman explaining the depth of the crisis and suggesting "concrete steps".

They have received no reply.

The same has gone for a second letter, sent at the end of October, to the head of the University Hospital, about Dr Machado's inability to treat the 468-long waiting list of cardiac patients. Again, no reply, no acknowledgment.

Dr Machado looks out at the roomful of junior doctors before him. Several of them are in tears.

"We are in a humanitarian crisis," he tells me. "Our country may be wealthy, but it is poor."

- Published1 December 2015

- Published26 November 2015

- Published20 April 2015

- Published16 January 2014

- Published9 September 2024