Venezuela: Economy on the brink?

- Published

Venezuelans voted in legislative elections on Sunday

Venezuelans went to the polls on Sunday to elect all 167 members of the National Assembly amid tension caused by the country's worsening economic decline.

The MUD opposition coalition won a majority of the seats.

But it will now face a long catalogue of economic problems.

Not only has Venezuela been hit hard by the continuing low price of oil, its main export, it also has the continent's highest inflation rate and is suffering from chronic shortages of some basic goods.

President Nicolas Maduro blames the poor state of the economy on an "economic war" waged against his government by the opposition, a foreign axis of shadowy players based in Miami, Madrid and Bogota, and private firms intent on toppling his administration.

The opposition meanwhile say the economy has been run into the ground by government mismanagement and the administration's imposition of price and currency controls.

Daniel Gallas looks at five key issues troubling the economy.

Oil

Venezuela's economy is closely linked to the price of oil - which accounts for more than 90% of the country's export revenues.

State-owned oil company PDVSA has been severely hit by low oil prices

As prices tumbled in the past months - from $115 (£69) a barrel in June 2014 to below $50 last month - the country's GDP took a nosedive.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts that the economy will contract 10% this year and a further 6% in 2016.

President Maduro has been pressing the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) - of which Venezuela is a member - to decrease production and push barrel prices up to at least $88.

However, most Opec countries are interested in maintaining prices relatively low, so as to disincentive shale-gas projects.

Caracas is bracing itself for oil prices to stay low.

Last week, the National Assembly approved the 2016 budget which predicts a price of $40 per barrel next year.

Shortages and queues

For the past two years, going to supermarkets in Venezuela has been a time-consuming affair.

Venezuelans often have to queue for hours to get hold of basic items

A study by polling firm Datanalisis suggests that Venezuelans spend on average five hours per week buying groceries and visit up to four different stores to find products.

Outside each major store, there are long queues and it takes hours for customers to get inside.

Chronic shortages of a number of products mean many have to go home empty-handed.

The hardest items to get hold of are the 42 staples the prices of which the government controls. Among them are milk, rice, coffee, sugar, corn flour and cooking oil.

Moreover, the Venezuelan Pharmaceutical Federation estimates that there is a shortage of 70% of medication in most pharmacies across the country.

Food companies complain that with regulated prices, some items are just not profitable to produce.

The government accuses producers of deliberately stockpiling products in order to drive prices up.

Venezuelan-based broadcaster Telesur recently alleged that the shortages were a "concerted effort by the opposition to create psychological distress in the country ahead of elections".

Inflation

With shortages and queues, prices for essential goods are skyrocketing in the black market, driving up the cost of living.

Inflation has skyrocketed

The IMF predicts annual inflation of 159% in Venezuela this year - the highest in any country in the world. In 2016 it could be upwards of 200%, according to the Fund.

Venezuela has not released any official inflation data this year, but President Maduro recently stated that figure for 2015 was likely to be 85%.

The government tries to tackle rising inflation with price controls; recently it fixed the price for a carton of 30 eggs at 420 bolivares.

But not all sellers stick to the fixed prices. Consumers reported paying almost three times as much on the black market, according to Huevo Today (Egg Today), a Twitter account on which Venezuelans share information on the prices of eggs.

Exchange rate

Venezuela has three official exchange rates and an illegal black market rate.

Getting hold of dollars is no easy task

The first two are used for importing goods which the government considers essential, such as food, medicine or household items. The third one is for Venezuelans who do not have the authorisation to buy dollars at the preferential rates.

But the black market rate is the one which many Venezuelans use as it is hard to get approval to exchange money at the official rates.

The disparity between the first rate and that of the black market is enormous. One dollar will buy you 6.3 bolivares at the lowest official rate, while on the black market it will fetch a whopping 800 bolivares, according to the widely used website DolarToday.com website.

The government introduced currency controls in 2003 to stem the flow of capital out of the country, but instead they have been a driving factor in pushing up inflation.

Importing goods can be prohibitively expensive and companies are forced to find local alternatives.

For 10 months, fast food chain McDonald's replaced its French fries with yuka fries - made with local cassava - because importing potatoes had become too dear.

French fries only returned to its menu last month when McDonald's finally managed to source potatoes locally.

Living standard

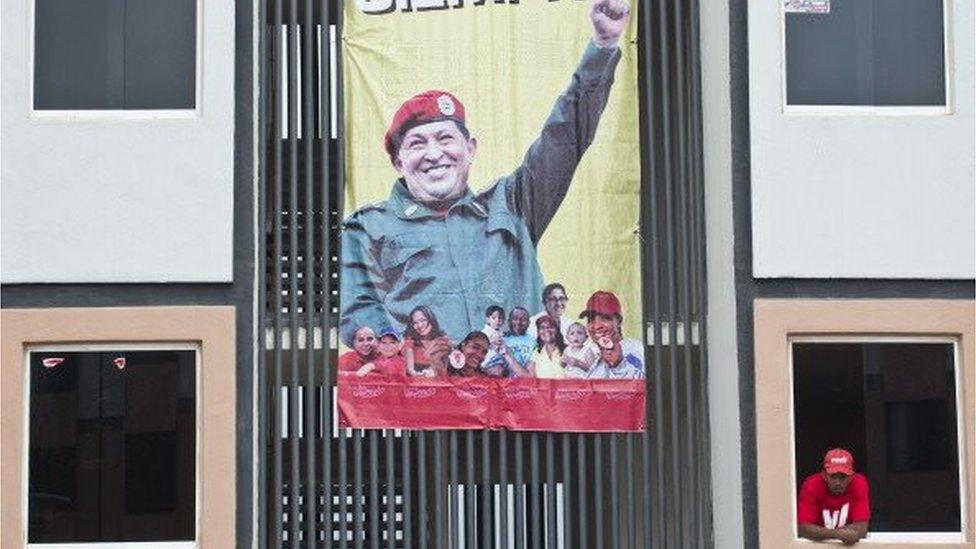

One of the proudest achievements of Chavismo - as the politics of the late President Hugo Chavez and his successor in office Mr Maduro are known - is its record in reducing poverty and inequality.

Venezuela's socialist government invested in social housing for the poor

Poverty levels were halved between 2003 to 2011 and Venezuela's Gini co-efficient, which measures inequality, improved greatly.

Social programmes sponsored by the government helped boost real income, but many fear that in a recession some of those gains are at risk of being reversed.

A recent study by three Venezuelans universities suggested that poverty had already increased massively. The study suggested 73% of the population now lived in poverty - up from 27% in 2013.

The government dismissed the study, saying that not only had poverty not risen but that extreme poverty had fallen in 2015.

Officials also said that unemployment had fallen to a historic low of 6.7%.