Argentines debate Kirchners' cultural legacy

- Published

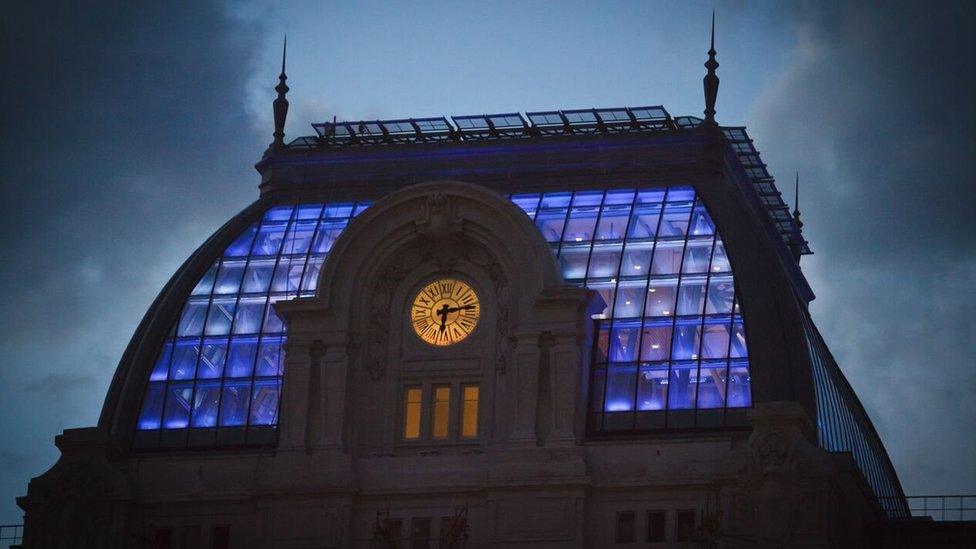

The Kirchner Cultural Centre was previously the headquarters of Argentina's post office

Only 500m (0.3 miles) from the presidential palace in Buenos Aires, there is a grandiose eight-storey building that occupies an entire block.

It is Latin America's largest cultural centre, with 116,000 sq m of galleries, auditoriums and concert halls.

It is one of the most visible legacies of former presidents Nestor Kirchner and his wife Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner.

After 12 years in power - which come to an end on Thursday with the swearing-in of president-elect Mauricio Macri - it is an example of one of their more controversial policies.

Some say the centre is an overpriced vanity project, while others argue it is a necessary investment in an underfunded area.

What's in a name?

The controversy starts with its name, engraved on the building's front: Centro Cultural Kirchner.

Parts of the interior were completely changed

"We would all be saying great things about this centre if it had a different name," explains Dario Loperfido, the newly-appointed culture minister for the city of Buenos Aires.

"The government pretended to build a place that gives importance to culture, but what stands out is the concept of self-glorification," he says.

Outgoing President Fernandez de Kirchner inaugurated the centre in May 2015, dedicating it to her late husband and predecessor in office, Nestor Kirchner.

Before it housed the cultural centre, the building was the headquarters of the Post Office.

Mr Kirchner was a child when he first entered it with his father, a Post Office employee.

Palatial surroundings

When it first opened in 1928, the Palacio de Correos (Post Office Palace) was the largest public building in Argentina.

It was so grandiose that in the 1940s, the president at the time, Juan Domingo Peron, spent a lot of time there as his wife, Eva Peron, had her foundation's headquarters inside the building.

The building was once used by President Peron as his headquarters

Details of the original decor were preserved during the renovation work

In 2010 - after the Post Office had moved to a smaller, more modern building - it became the new home of the Bicentennial Cultural Centre.

This was a few months before Mr Kirchner's death.

Two years later, Ms Fernandez de Kirchner signed a presidential decree changing the centre's name to that of her late husband.

State-of-the-art space

Aside from its controversial name, the state-run centre has been widely welcomed by musicians and music lovers.

Architects worked closely with Argentina's National Symphony Orchestra in order to create a state-of-the-art concert hall.

Original frescos, stuccos, marble hallways and stained-glass ceilings were maintained while the rest of the building - which was initially destined as offices and was not as magnificent - was completely transformed, using new, modern materials.

Timelapse footage of the construction of the concert hall

The Ballena Azul (Blue Whale) concert hall was mounted on shock-absorbing stilts and suspended in the middle of the building in order to avoid the vibrations created by the underground, which runs below the building.

The Ballena Azul (Blue Whale) concert hall is mounted on shock-absorbing stilts in the complex

The concert hall has since become the permanent seat of the National Symphony Orchestra, which had been homeless since its foundation in 1948.

Several Argentine-born musicians working abroad are being invited to play with the orchestra, which finally has a proper rehearsal space.

"Having a home, like in normal life, brings a sense of belonging," says Mariano Chiacchiarini, an Argentine conductor based in Germany who has been working with the National Symphony Orchestra over the past months.

No fee

But critics question the sustainability of the centre, which cost the government $2.5 million (£1.6 million).

Has time run out on the cultural centre's policy of offering culture for no fee?

It charges no entry fee and also takes its shows and workshops to other provinces for free.

This is in stark contrast with other art spaces in Buenos Aires.

At the Colon Theatre, an opera ticket costs up to 3,000 pesos ($300; £200), half the monthly minimum wage.

Mr Loperfido, who is the director of the Colon Theatre as well as the city's culture minister, says that in the long run it is not possible to sustain a place of excellence without charging.

"Things are never free," he argues.

"Everybody pays through taxes. It's best to charge fewer taxes and let people do what they want with their money."

Artistic freedom?

Others allege the centre is not politically independent.

Federico Andahazi, one of Argentina's best-known contemporary writers and an outspoken critic of the Kirchner era, says the centre is "a perfect metaphor of these [Kirchner] years".

"Kirchnerism used culture to advertise itself."

The cultural centre is one of the more visible legacies of the 12 years in power of President Cristina Fernandez Kirchner and her late husband, Nestor Kirchner

Looking at the programme, there are plenty of signs of political affiliation, such as the permanent exhibit celebrating the life of President Nestor Kirchner.

But a large part of the programming has undoubted artistic value.

For example, in July, the symphony hosted Argentina's own Martha Argerich, one of the world's great classical pianists.

Over one million people tried to book tickets for the concert in the auditorium, which can seat just under 2,000 people.

Public television broadcast the show live.

Playwright Mauricio Kartun says the centre may appear excessive in terms of size and offer, "but when one compares it with the huge cultural offer and demand in Buenos Aires, it seems quite appropriate".

He believes that access to culture is as important as access to health and education and should be managed by the state.

"Culture is not an ornament or a pastime. Culture is a door to inclusion," he argues.

When he moves into the presidential palace on Thursday, newly elected President Mauricio Macri will be within earshot of the centre.

Vanity project or not, Buenos Aires' music and culture lovers are hoping his government will continue to invest in the centre so it can establish itself as a cultural hub free from political ties.