Brazil Rio: An education clouded by violence

- Published

Twins Samira and Samir da Silva, 11, describe what it is like growing up in a Rio shanty town and how violence affects their lives.

Samir wants to be a veterinarian and Samira wants to be a dentist.

The 11-year-old Brazilian twins have just finished the school year but before they can set out on their dream careers they have to overcome some hurdles in their education.

They have missed countless schooldays this year because of frequent shoot-outs in their area.

And they are not alone.

According to the city hall education office, 129,000 students in Rio de Janeiro had classes cancelled at least once between January and October because of outbreaks of violence in the 300 or so public schools located in violent areas of the city.

The twins live in Complexo da Mare, a sprawling poor area of Rio wracked by gang violence.

When there are shoot-outs, the twins play on the rooftop with their dog Princesa

"When there are shoot-outs we can't go to school," says Samir in the small house he shares with his mother, grandmother and two sisters.

"So we stop studying and stay home. What can we do?"

On other days, they were stuck at school while shots rang out around them.

The outbreaks of violence in Mare were so frequent this year that the local authorities shortened the school day to lessen the risk of students being caught in crossfire between gangs and the police.

Classes now start at 08:00 rather than at 07:15, and finish at 11:30.

"Seven AM is critical because police change their shifts, so that's when the shooting starts," explains Glauce Arzua, campaigns coordinator at ActionAid, a non-governmental organisation which works with local organisations to defend residents' rights.

But the new timetable means that students miss 75 minutes each class a day, a big setback to their education, Ms Arzua argues.

Complexo da Mare is home to about 140,000 people.

Last year, ahead of the World Cup, security forces occupied the area to implement the state's "pacification policy", which seeks to establish a permanent police presence in the area.

Mother's view

But the twins' mother, 46-year-old Sirlene da Silva says the "pacification policy" has actually increased tension in the area and clashes have become more frequent.

The twins while away the time playing computer games and watching TV

Ms Silva is on the minimum wage (around $250; £168 per month) and cannot afford to send her children to a private school in a safer area, so the family has little choice.

"We live in the crossfire," she says. "There's violence from criminals and violence from the police.

"When the police come in, they shoot first and ask questions later.

"When there are police operations, the kids can't go to school, the teachers can't come to class and the residents can't go to work."

The Rio authorities say extra classes are held to compensate for violence-generated gaps, and assure all schools fulfil the 200-day school year.

Psychological effects

But the problem goes far beyond timetables.

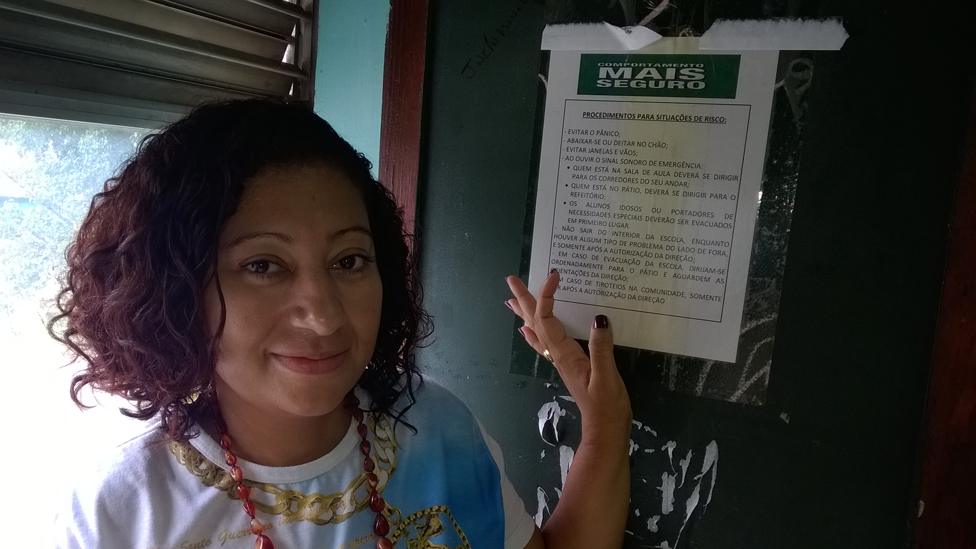

Roberta de Sousa, 38, has been a teacher in a state school in Mare for eight years.

Roberta de Sousa makes sure pupils know what to do in case there is a shoot-out

She says the frequent outbreaks of violence seriously undermine the children's performance and self-esteem.

"They go to school hoping it will lead to a better life, but instead, violence invades the walls. They feel that here, too, they are abandoned as citizens and aren't entitled to their basic rights," she explains.

Ms Sousa says she has had to switch classrooms or seek refuge in the school corridors for fear that bullets would come through the windows.

"I've had to teach literature with a shoot-out raging outside. It's not easy."

She is one of the teachers trained through a partnership between the state of Rio and the International Committee of the Red Cross to reduce the impact of violence on education.

'Stay safe'

Since 2009, the programme has been training teachers to deal with the violence which surrounds the pupils in both practical and psychological terms.

This ranges from drills on how to stay safe during shoot-outs to debating problems in class.

"Children don't talk about violence openly for fear of being punished," says Patricia Tinoco from Rio state's education office.

"We create a room for dialogue and this helps them deal with fear and understand what's happening."

She says that while pupils' performance has been consistently below average in troubled areas, the programme has led to improvements.

Meanwhile, Samir and Samira dream not only of their future careers but also of earning enough money to be able to leave Complexo da Mare and move somewhere safer.

Their mother hopes the constraints they are currently living under will not affect their chances of achieving their dreams

"I can't offer my children the education they deserve," she says. "It's a huge disadvantage but I have to have faith the situation will improve, or else nothing will make sense."