Venezuela's decline fuelled by plunging oil prices

- Published

People queuing for basic commodities are a common sight in Venezuela

Venezuela is a country of superlatives. Many of them, alas, are not particularly desirable: the world's largest proven oil reserves; the world's highest rate of inflation; the world's worst performing economy etc.

The South American country now has another "title" to add to that list: that of the world's most murderous nation.

A recent report by the Venezuelan Observatory on Violence (OVV) calculated that the 2015 murder rate was a shocking 90 per 100,000 residents, a figure considerably higher than other "hotspots" for violence like Colombia and Mexico, and 20 times the homicide rate in the United States.

"The cause of the violence in Venezuela is the breakdown in the social pact," says Professor Roberto Briceno Leon, director of the OVV.

"The idea of the social relationship, regulated by law, has been destroyed by the government, for political reasons. In their revolution, everything has to be changed," he somewhat grimly concludes.

Thriving black market

Later on, looking down on the sprawling Venezuelan capital, it is not difficult to understand why it feels as though Caracas and the country are falling apart.

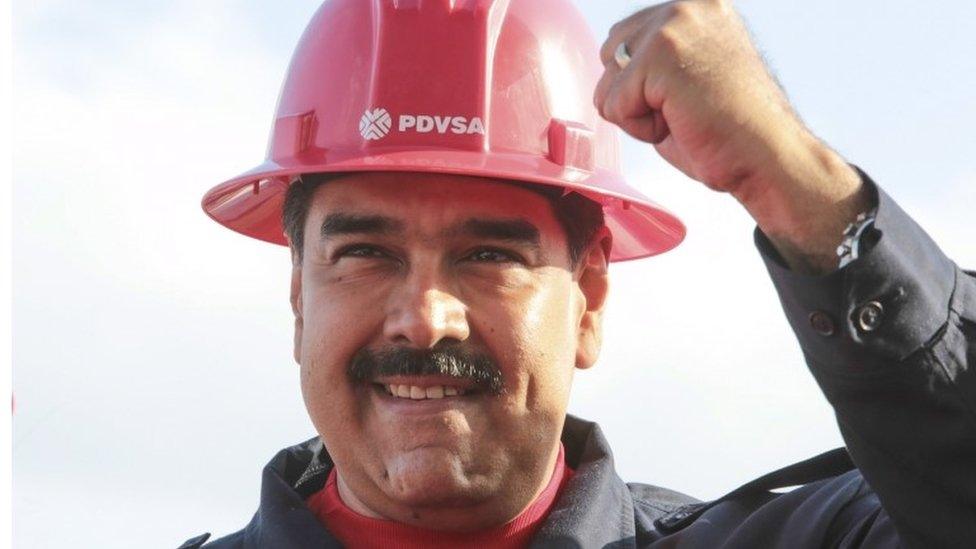

Last month the embattled socialist President, Nicolas Maduro, finally recognised reality and declared an economic emergency

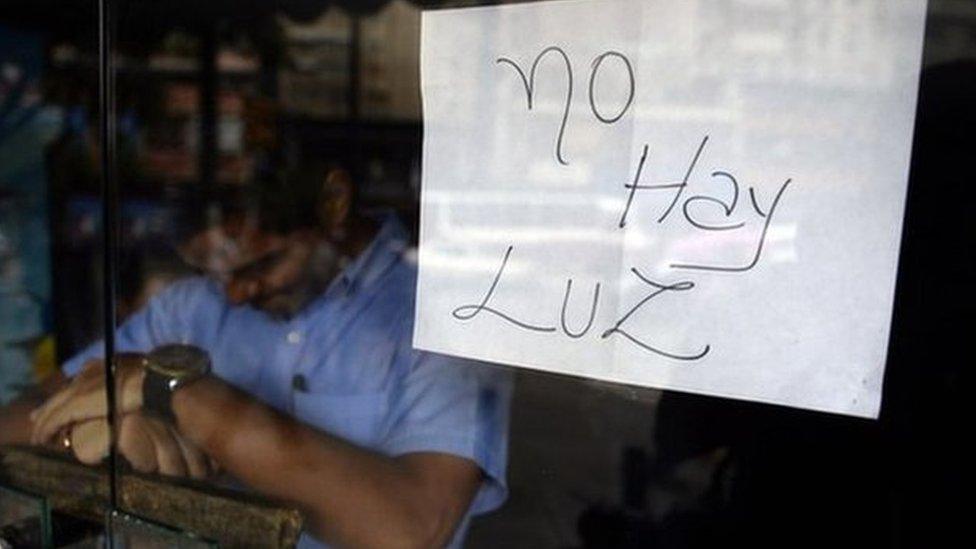

Everyday food is in short supply

The narrow, steep and winding streets of the Petare slum are, in reality, run by organised criminal gangs rather than by officials from the city below. There is no permanent police presence, only the occasional armed patrols driving through.

Police pay scant attention to the many informal street stalls selling everything from toilet paper to detergent to cornflour. This is the thriving black market system that now props up Venezuela's sickly economy.

Many of these basic goods have found their way here from the official government stores in the city. There, prices are regulated but everything, including rice, oil, meat and washing powder are in desperately short supply and people have to queue for hours, often in vain.

Venezuela, its oil-dominated economy in crisis, can barely afford the dollars to import foodstuffs and manufactured goods. In a disastrous move, the country long since bet everything on the price of oil remaining high and allowed its other industries to be run into the ground.

Last month, embattled Socialist President Nicolas Maduro finally recognised reality and declared an economic emergency, at the same time assuming extraordinary decree powers.

'Economic warfare'

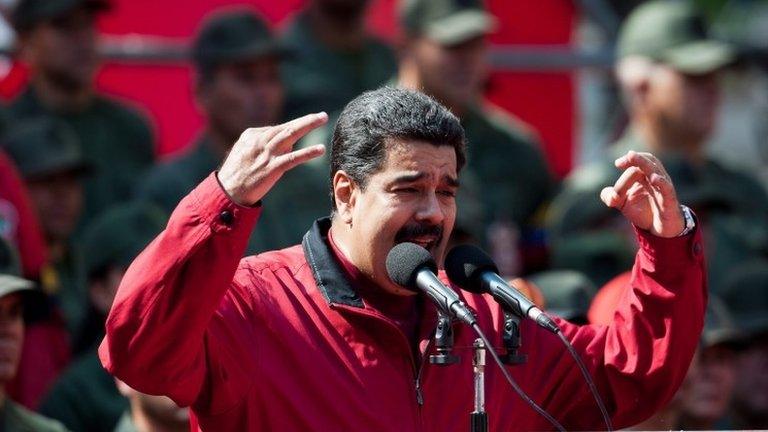

But it increasingly seems more of a political attempt to emasculate the opposition-controlled congress, rather than a change of course after 17 years of socialist "Chavista" rule.

Venezuela's economy has been pushed to the brink by the collapse in the oil price

In a disastrous move, the country long since bet everything on the price of oil remaining high and allowed its other industries to be run into the ground

Residents of Caracas require food tickets to buy everyday essentials

Indeed, after another heated debate in congress this week, a government politician repeated the long-standing argument that the country's problems were all the result of internationally backed "economic warfare".

"It's North American imperialism. The United States has no morals or ethics," says Pedro Carreno. "They have no respect for international norms or law and will do anything to destabilise us," the socialist deputy tells me.

While Washington certainly has a long and dark history of interfering in the internal affairs of many Latin American nations, the fault for most of Venezuela's current woes almost certainly lies within.

And oil has been more of a curse than a blessing.

For decades Venezuela gave oil away, to its allies in the region and to its own people but as oil prices and revenues crashed, something had to give.

Oil industry analyst Victor Poleo says that Venezuela is the architect of its own destruction

Life for ordinary Venezuelans has become far harder in recent months

President Maduro increased prices for petrol this week by 6,000% - a huge hike, but fuel is still very cheap. With inflation expected to reach 700% this year (according to the International Monetary Fund) it will hardly make an impression on the real costs of production or the government's colossal debts.

But it is all too little, too late, says Victor Poleo, an oil industry analyst and former energy minister.

"It's gone: my impression is that oil is being replaced. The energy industry is changing and we are in a bad position because we didn't invest," he says.

"In 10 years we've destroyed 100 years of our energy industry. It's very destructive. There is no country committing suicide like Venezuela," Mr Poleo tells me as we pore over a map showing the extent of Venezuela's oil-producing areas. Much of the oil is arguably no longer worth bringing out of the ground.

Determined to see out his six-year presidential term, Nicolas Maduro has promised to defend the social gains of his predecessor Hugo Chavez's Bolivarian revolution.

His opponents in congress have vowed to use constitutional measures to force his early removal but Mr Maduro will probably be protected by the openly pro-government Supreme Court.

The real danger for Venezuela is that nothing will change for the better. Its young people will continue to leave, poverty will worsen and there will be no political reconciliation as this potentially wealthy nation slips slowly but surely ever backwards.

- Published18 February 2016

- Published17 February 2016

- Published12 February 2016

- Published8 February 2016

- Published7 January 2016