Venezuela's farmers: 'Planting for the revolution'

- Published

Jose Braulio Diaz is grateful to the late President Hugo Chavez

Jose Braulio Diaz has his own plot of land where he tends 120 coffee plants.

He is one of thousands of landless labourers who have received land titles from the Venezuelan government.

"We used to be treated like slaves by the big landowners," he says.

"Now thanks to God and to Comandante Chavez we are free from that," he says referring to the former president of Venezuela, Hugo Chavez.

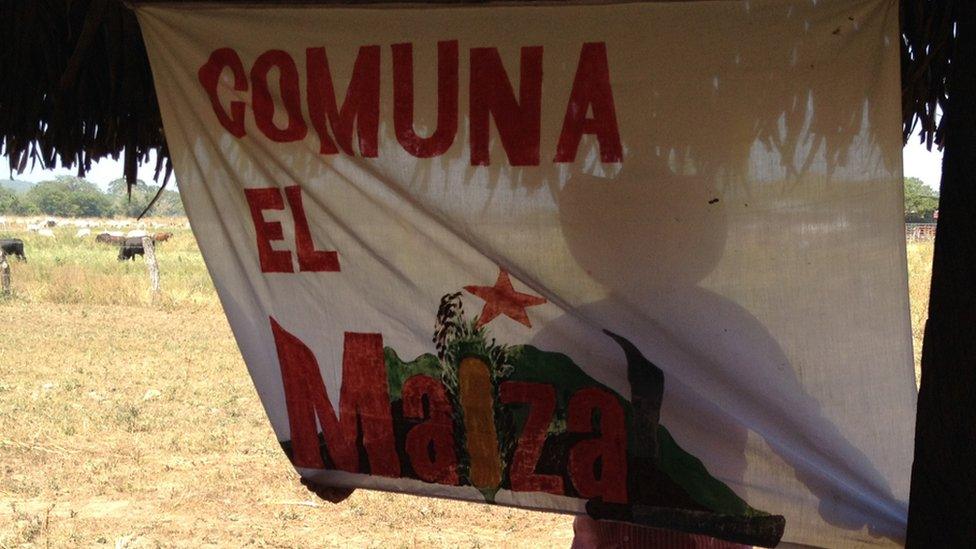

Mr Diaz lives on the Maizal commune, which lies on the plains and mountains of two states, Lara and Portuguesa.

The residents of Comuna El Maizal are proud of what they have achieved

They say they have produced 35,000 kilos of black beans

The people who live and work in El Maizal are reluctant to give up their land

Two thousand families live on this land, which was expropriated by the government from its previous owner in 2009.

Many members of the commune, like Mr Diaz, have their own small plot of land, and also work together in the commune's large maize fields.

The commune has a clinic and a school.

Venezuela's parliamentary opposition says the expropriations were arbitrary and lawless; it has proposed a new law which would allow former owners to claim back expropriated land.

But people here say they will not give up the land easily.

"We won't let the big landowners come back and make us slaves again," says Mr Diaz.

Loyal support

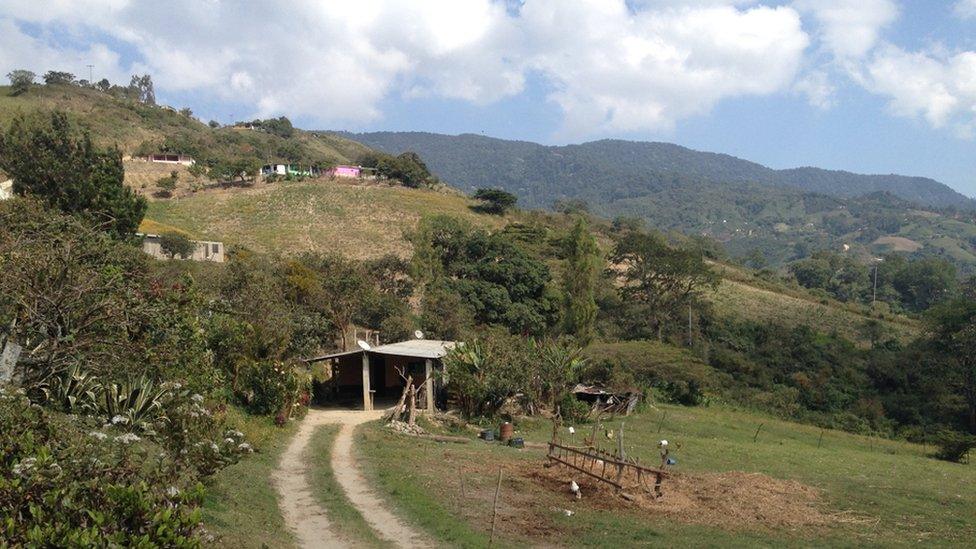

The cool mountain villages of Palo Verde and Monte Carmelo lie in the foothills of the Andes, a few hours' drive from the Maizal commune.

Support for the government is strong among smallholders in Monte Carmelo

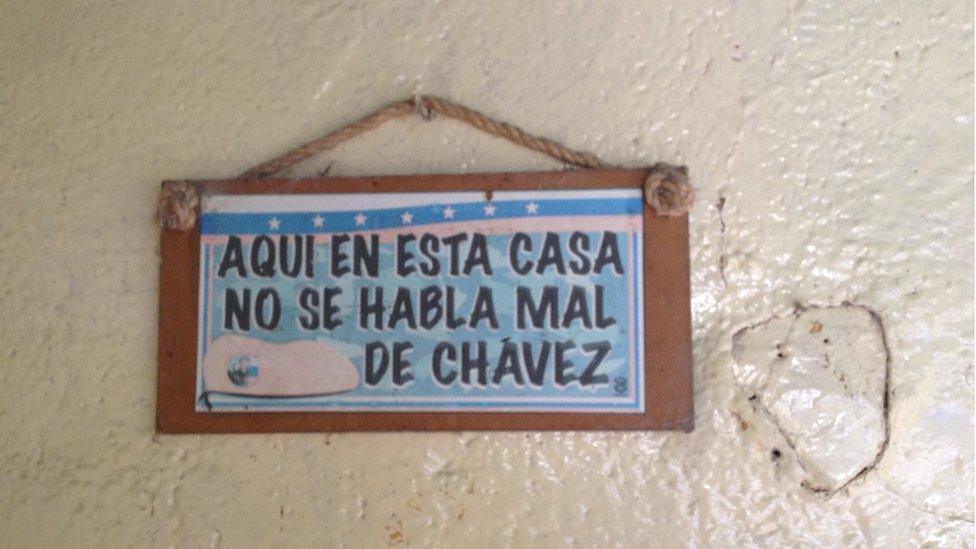

A sign on a house in Monte Carmelo reads "In this house no one talks badly about Chavez"

Here, too, many of the smallholders support the government.

While the opposition won a resounding two-thirds victory in last December's parliamentary elections, in this rural region, pro-government candidates swept the board.

Erica Silva's husband rents a smallholding growing yucca and black beans.

They live in a brightly painted new house built by the government.

"I support the revolution 1,000%," she says.

Erica Silva is pleased to be studying again

"The government has built houses, sold cheap food and opened a hospital. They have done many beautiful things."

She is enrolled in the government's education programme, Mission Robinson. "I left school at 14, now I am studying again."

So if Venezuela's small farmers are cultivating crops, why has Venezuelan food production stagnated and actually declined in per capita terms?

Eligio Lucena says he cannot get hold of seeds

To answer that question you need to speak to farmers who are not rich but who have slightly more land and on whom Venezuela used to rely to grow food for the market.

Eligio Lucena rents a few hectares of land and employs up to 12 people to cultivate potatoes.

He says the government's tight controls on imports have made it impossible to get hold of seeds and fertilizer.

"It's crippling us. Many people round here have the land all prepared for sowing, but we can't get hold of the seeds."

His father, Jose, used to herd sheep, goats and pigs, but says that the government's price controls destroyed his business.

Jose Lucena says government price controls have ruined his business

His small farm now looks barren without the animals he used to farm

"[Hugo] Chavez sold meat so cheaply, he was practically giving it away, and no-one round here would buy my pork anymore."

Many basic foodstuffs, such as maize flour, rice, beans, milk and eggs, are in such short supply that they are now rationed by the state.

The government blames the shortages on an "economic war" by big landowners and food companies which, its says, are refusing to produce and distribute food in order to undermine the left-wing government.

But this charge is rejected by Carlos Odoardo Albornoz, the president of the Venezuelan federation of cattle ranchers.

"If we had wanted to destabilise the government, they wouldn't have been in power for the last 17 years, would they?"

The real problem, he says, is that while world oil prices were high, the government relied on food imports, which were sold at such low prices that it was impossible for Venezuelan farmers to compete.

Shortages of basic items have triggered protests in Caracas

Now that oil prices have fallen and the country has fewer dollars to spend on imports, the Venezuelan agricultural sector is too weak to fill the gap.

"In the last ten years, we have had a policy of relying on imports, which has destroyed the national productive apparatus, not only in the countryside, but in industry and transport.

"This is an economy that has been driven by ideology and slogans, with little incentives for national producers," he says.

Many small farmers say the revolution has improved their lives.

Poverty levels were falling and nutrition levels were rising until the collapse in world oil prices pushed Venezuela into economic crisis.

But now, as queues and shortages plague Venezuela, the policy of using oil dollars to pay for cheap food imports, at the expense of the country's own farmers, looks very short-sighted.

- Published18 February 2016

- Published4 February 2016

- Published7 January 2016