Lula: The most hated and loved man in Brazil

- Published

Demonstrators for and against Lula. The banner reads: 'The boss knows about everything"

February can be a sleepy month in Brazil. As it marks the end of summer, most big cities are empty, with millions still taking it easy with carnival and holidays in the beach towns.

But on the morning of 17 February, dozens of people gathered in a stand-off in front of a criminal court in Sao Paulo.

Former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva had been invited by authorities to give a statement in that court about a series of properties that it is alleged were gifted to him by corrupt executives.

Pro and anti-Lula demonstrators met and clashed in front of the building. The anti-Lula movement tried to inflate a gigantic doll that shows the former president wearing a prisoner's striped clothes.

His supporters quickly intervened and tore up the doll.

Demonstrators clashed with each other - and with the police

In the end, Lula didn't even show up - he secured a court order dismissing the appointment. But that did not deter violent clashes from taking place, with a few people injured and a heavy police reaction.

Divisive figure

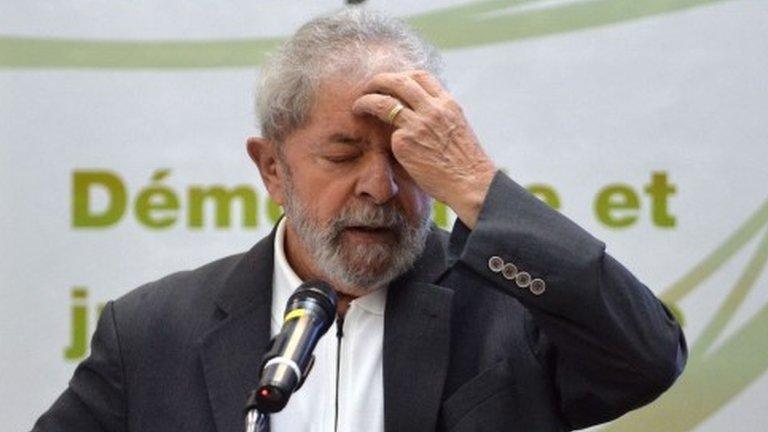

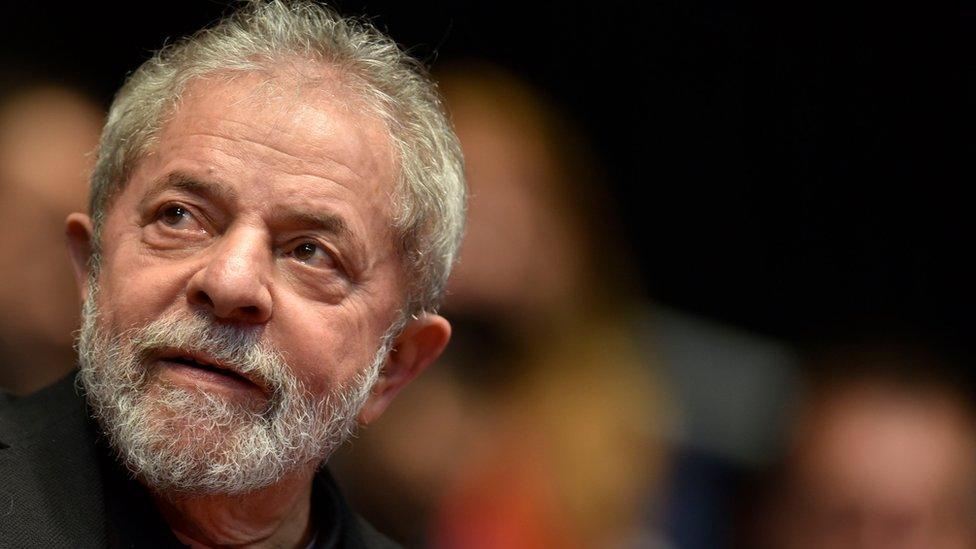

No-one in Brazil can stir up as many passionate reactions as Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva.

Lula has been a central figure in Brazilian politics since the 1970s, rising spectacularly from a very poor background to the nation's top job.

Lula: 'Man of the people'

Born 27 October 1945 into a poor, illiterate family in Pernambuco state

Worked in Sao Paulo's car industry

Achieved national fame leading strikes during Brazil's dictatorship

In 1980 he founded the Workers' Party (PT), the first major socialist party in Brazil's history

Elected president in 2002 at the fourth attempt and went on to serve two terms

Pumped billions of dollars into social programmes such as Bolsa Familia that benefited tens of millions of Brazilians

When he left office in 2010 he said: "I am leaving government to live life on the streets. Man of the people that I always was, I will be more of the people than ever before."

Currently under investigation over his deals with construction firms

He is simultaneously the most loved and hated figure in Brazil, and people's perceptions of him tend to manifest themselves in extremes.

Some see him as the man who finally defeated an elite that had been in power for centuries and who used his powers to better the lives of the masses.

Millions of Brazilian families have received funds from the Bolsa Familia programme

Others say Lula is a corrupt populist whose only real project was to perpetuate his party's stay in power through dodgy deals and alliances.

These extreme views make it all the harder for investigators, the press and the general public to determine whether he was in fact involved in suspicious deals with corrupt firms, or whether he is simply a victim of a major stitch-up, as he claims.

Accusations

The case prosecutors want to bring against Lula is simple enough.

Investigators say corrupt construction companies that had very lucrative deals with state oil giant Petrobras were gifting the former president millions of reais for his charitable think tank, a country house and a three-storey beachside apartment.

The probe centres on a luxury penthouse in the resort of Guaruja

In exchange, Lula would have used his towering influence over the Workers' Party government to ensure that key Petrobras positions would be held by corrupt executives.

This would guarantee that construction firms like OAS and Odebrecht would always get favourable and inflated contracts with Petrobras.

Some facts are well-established in the investigations.

More than $2bn (£1.4bn) was indeed siphoned off from Petrobras - the company itself has acknowledged that in its accounts.

Earlier this week the head of the Odebrecht construction group was sentenced to 19 years in prison for his role in the scandal. Many other construction company bosses are behind bars, awaiting trial or sentencing.

Lula acknowledges that some of these construction firms have paid millions to him. The former president is a successful public speaker and charges big money for speeches. He claims there is nothing wrong with that.

Question marks

Beyond that, there are more questions than answers.

So far, there is no concrete evidence that Lula ever intervened in Petrobras nominations. And there are not yet any documents that prove that the former president owns the beachside apartment and the country house his family regularly uses.

Despite that, on Wednesday Sao Paulo state prosecutors decided to bring charges of money laundering against Lula, as part of a separate investigation.

A judge must still formally accept the charges against Lula da Silva for the case to proceed

They say Lula is the real owner of the beachside apartment, but a judge still has to decide whether to accept these charges.

Also, Delcidio do Amaral, a key ally who was the government's leader in the Senate, is reported to have turned against Lula and President Dilma Rousseff, and could provide some of the missing links in the investigations.

Paralysing the country

The "Lula question" is all but paralysing Brazil, as the country faces its worst recession in more than two decades.

Demonstrations for and against him are planned up and down the country.

Both popular and political support for President Rousseff's government hang partly on whether Lula is corrupt or not.

The Workers' Party under President Rousseff may be nearing the end of an era in Brazilian politics

"The question of whether the former president really is the owner of the country house and the beachside apartment should be treated as a separate problem, but in Brazil's current tense environment it has become a central question in politics," says Carlos Melo, a political scientist at Insper Business School.

Lula's achievements in his lifetime - both good and bad - are often measured in superlatives.

His government is credited with having lifted millions out of poverty through economic growth and cash-transfer programmes - no small feat in a country with one of the highest levels of income inequality in the world.

This garnered him international fame, and hero status among Brazil's poorer classes and left-wing intellectuals.

But also under his rule, the Workers' Party was found guilty of operating the "Mensalao" - which before the Petrobras probe was the country's biggest ever corruption scandal.

Lula, who rose to prominence promising to rid politics of corruption, saw many of his Workers' Party peers jailed for paying monthly bribes to MPs and senators in exchange for political support.

Lula came to power in 2002 promising major economic and political reforms

His critics often cite the Petrobras and Mensalao scandals to point out that Brazil has never been more corrupt than under his rule.

Brazil's top broadsheets and mainstream magazines, who openly criticise his politics in editorials, have dug up many allegations and accusations against him.

Legacy

It is not just Lula's reputation that is under the spotlight with these investigations, but also the legacy of 14 years of left-wing rule in Brazil and the survival of this project in the future.

Lula left office in 2010 with record-breaking approval ratings and saw his chosen successor elected and then re-elected four years later.

A few years ago, the Workers' Party seemed almost unbeatable as Lula slowly faded into retirement.

What does the future hold for the Workers' Party (PT)?

But with Brazil in severe economic crisis and its most renowned politician under investigation, things have changed.

Now the Workers' Party suddenly sees itself near the end of an era in politics.

Lula is not going down quietly though. On the contrary, he seems to thrive on adversity and confrontation.

Last week, just minutes after he had been detained for questioning by the police, he gave a fiery speech in a press conference that was broadcast live across the nation.

Often on the verge of tears, he maintained his innocence and accused Brazil's elite of trying to annihilate him politically.

As usually happens with Lula, his speech brought many people out onto the streets - both in favour and against him.

Pro and anti-Lula campaigners held a demonstration in Congonhas airport where the ex-leader was questioned

On the day he was detained, there were clashes in front of his house and at the airport, where he gave his statement.

Lula has offered himself up as a candidate for 2018 and has vowed to once more defeat his enemies - the opposition parties, the media and the prosecutors.

Brazil is now braced for nationwide anti-corruption protests that will take place on Sunday.

Unlike in previous demonstrations, this time Lula supporters are saying they too will take to the streets.

All the angry feelings that have so far been expressed only in social media debates may soon be about to burst onto the streets.

- Published10 March 2016

- Published4 May 2016

- Published4 March 2016

- Published4 March 2016

- Published16 September 2015

- Published22 April 2015

- Published11 June 2019

- Published2 June 2023