ELN peace talks: What are the challenges?

- Published

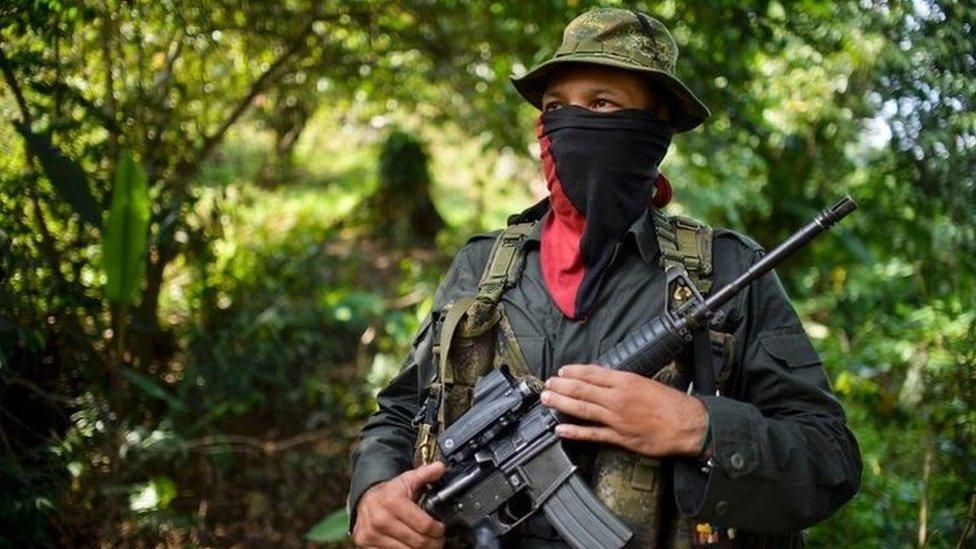

The ELN is Colombia's second-largest rebel group

The National Liberation Army (ELN), Colombia's second-largest rebel group, has entered into formal peace talks with Colombian government negotiators.

The talks are aimed at ending more than five decades of armed conflict. Here, we take a closer look at the discussions ahead.

Were talks not due to start last year?

In March 2016, government negotiator Frank Pearl and ELN rebel Antonio Garcia said they would engage in formal peace talks

Yes, the ELN and the government first announced their intention to start formal peace talks at a news conference on 30 March 2016.

They had originally been expected to start in May 2016, but did not go ahead.

Later, the two sides said the negotiations would start in the Ecuadorean capital, Quito, on 27 October, but that date also came and went.

A new date was set for 7 February 2017.

Why all the delays?

The government said it would not start formal talks until the ELN released Odin Sanchez

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos said that a precondition for the talks was the release of hostages the ELN was holding.

The ELN has long used kidnapping for ransom as a means of financing itself. It also considers the kidnapping of soldiers and police officers a legitimate tactic.

The rebels eventually agreed to free a soldier they had recently seized and former Congressman Odin Sanchez in exchange for a pardon for two of its jailed members.

The move finally paved the way for formal talks to start.

However, future delays cannot be ruled out as the ELN has been reluctant to hurry the negotiations along.

In an answer to an open letter by Colombian intellectuals asking the rebels to negotiate speedily, ELN leader Nicolas Rodriguez said that "for the ELN, setting a deadline for peace means obstructing it".

What is on the agenda?

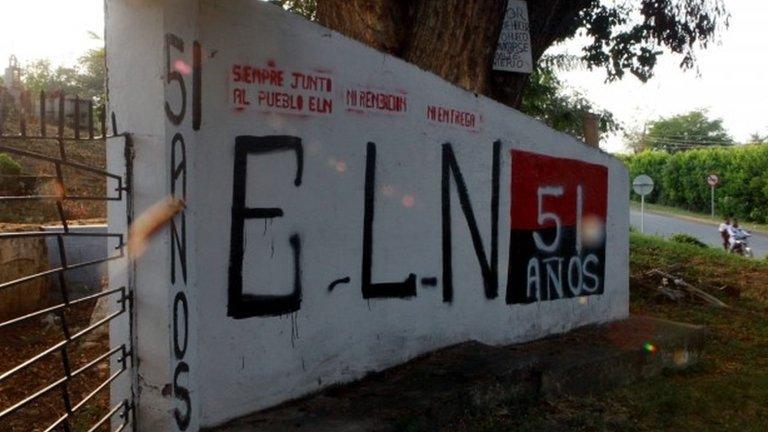

The ELN claims that it is "always close to the people"

President Santos has set his aims high. He says he wants to "achieve complete peace".

The ELN says it also wants peace but Mr Rodriguez, better known as Gabino, says he does not want the negotiations just to be between the government and the ELN but for civil society to be involved, too.

The six points on the agenda are currently rather vague. They are:

Participation of civil society in peace building

Democracy for peace

Transformations for peace

Victims

End of the armed conflict

Implementation

What does the ELN want?

The ELN has been fighting the Colombian state for more than five decades

The group was founded in 1964 and follows a Marxist-Leninist ideology.

It was inspired by the Cuban revolution of 1959 with an aim to fighting Colombia's unequal distribution of land and riches.

It feels particularly strongly that the country's oil and mineral riches should be shared among its people rather than exploited by foreign multinationals.

Over the decades, the guerrilla group has attacked large landholders and multinational companies. It has repeatedly blown up oil pipelines.

In the talks, its representatives are likely to call for social change to achieve more equality and for the inclusion in politics of Colombians whose voices they say have gone unheard for too long.

How big is the ELN?

The ELN has fewer members than Colombia's largest rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc)

The ELN is believed to have fewer than 1,500 active fighters, according to intelligence reports seen by Colombian media.

They are backed up by a larger number of "militants" or sympathisers who provide logistical support and back-up.

Its strongholds are in rural areas in the north and on the border with Venezuela, and also in the provinces of Casanare, Norte de Santander and Cauca.

The ELN is made up of regional commandos which have a certain degree of autonomy, which could make implementation of any deal hard to achieve.

How likely are the talks to succeed?

Peace talks held between 2002 and 2007 failed. The government said the ELN "lacked commitment"

Both sides say they are completely committed to the negotiations succeeding.

The government would like to see a deal signed before the presidential election in May 2018 but the ELN has said it will not be rushed.

Observers of the peace process think the ELN may prove harder to negotiate with than Colombia's largest rebel group, the Farc, with whom the government signed a peace deal in November.

That is because the ELN is less hierarchical in its structure and its members are believed to be more wedded to their Marxist ideology than the Farc.

The ELN also has not yet sworn off kidnappings for good, something the government says it will demand.

Previous peace talks with the ELN failed. But analysts say the current talks will benefit from the experiences gained from the successful negotiations between the government and the Farc.

What happens next?

The two sides hope to reach an agreement so the conflict can end after 53 years

After a ceremony marking the beginning of the formal peace talks on 7 February, the two sides are due to get down to the business of negotiating on 8 February.

The opening and closing rounds are scheduled to take place in Ecuador, but the current plan is for the other rounds to take place in the other countries acting as guarantors: Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Norway and Venezuela.

However, the head of the government delegation has lobbied against this plan, arguing it will cause too much disruption and delay the process unnecessarily.

- Published28 February 2016

- Published17 November 2015

- Published12 February 2015