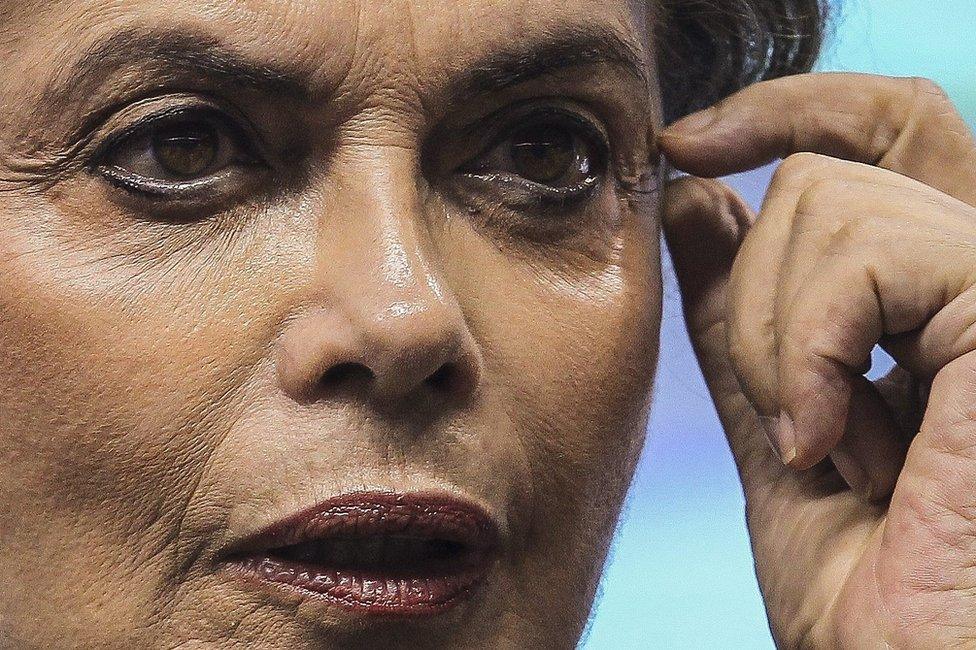

Dilma Rousseff impeachment: How did it go wrong for her?

- Published

It has been a sharp, quick decline for Ms Rousseff and the Brazilian economy

It was only a year and a half ago that 54.5 million Brazilians went to the polls to re-elect Dilma Rousseff in one of the world's largest democratic elections.

She defeated a centre-right coalition of parties by a narrow margin and earned a mandate to carry on the legacy of the centre-left Workers' Party, which has been governing Brazil since 2003.

But now she has been suspended from office and is to stand trial, accused of manipulating the government budget. And she faces the real possibility of being removed from power in six months.

So how did things get to this point - for a president who only three years ago enjoyed 80% approval, according to one poll?

Clean record

Brazil has seen all sorts of scandals since Ms Rousseff's second swearing-in last January.

Brazil's economic woes started in 2011, when China began to decelerate and Brazilian commodities began losing value

From billions being stolen from state oil giant Petrobras by private construction firms and politicians, to a powerful senator negotiating for a key witness to flee from jail, the country has been rife with jaw-dropping corruption revelations.

Virtually the whole political class has been implicated in some sort of dodgy deal.

Yet with all the investigations into corruption, one person has managed to keep a fairly clean record - President Dilma Rousseff.

Even her opponents tend to acknowledge President Rousseff's reputation as a honest politician.

Ironically, she is the one who may end up paying the highest price for many of the scandals Brazil is now facing.

Economy, not corruption

Ms Rousseff's personal record on corruption may be untarnished so far - but her handling of the economy has been highly controversial. And this is the argument the opposition has been advancing to get her impeached.

Brazil's economic woes started in 2011, when China began to decelerate and Brazilian commodities began losing value in international markets.

Brazil political crisis: Why Dilma Rousseff faces impeachment calls

The country had just come from a decade of solid growth and strong income redistribution.

The president and her team treated the decline as temporary and set in motion expensive stimulus measures to keep the nation's finances growing until the global outlook recovered.

But China's slower pace became the new normal, and all the measures taken by Brazil's government soon became unsustainable.

Despite that, Ms Rousseff won the election by promising to keep the stimulus in place and criticised opponents who said an adjustment - such as higher taxes and budget cuts - was needed.

But once re-elected, she single-handedly opted for an aggressive fiscal adjustment, angering those who voted for the opposition and leaving her own supporters feeling betrayed.

Creative accounting

Making what critics say are bad decisions on the economy is not a crime. But one of the measures taken by Ms Rousseff and her team back in 2014 was deemed illegal by a federal court that analyses federal accounts.

Billions have been stolen from state oil giant Petrobras by private construction firms and politicians

Brazilian governments are required to meet budget surplus targets set in Congress. Ms Rousseff is accused of allowing creative accounting techniques involving loans from public banks to the treasury that artificially enhanced the budget surplus.

This gave the appearance that government accounts were in better shape than they actually were. The surplus is one of the measures taken into account by investors of how sound an economy is.

Ms Rousseff has always maintained she did not act criminally in budgetary affairs.

She says many other presidents, mayors and state governors always used the same creative accounting techniques and were never punished for them.

The president says this is merely being used as a legal excuse - that her impeachment is nothing but an attempted coup by the opposition.

Rapid fall

While that debate took place, Ms Rousseff failed to carry out her fiscal adjustment plan.

After making cuts to unemployment benefits and ministerial budgets, the economy started contracting at such a fast pace that government revenues decreased sharply.

Ms Rousseff's Finance minister Joaquim Levy - who was supposed to carry out her reforms - left his job in December and the government virtually abandoned its surplus targets.

The year 2015 was disastrous for Brazil's economy.

By early 2016, the country had shed about 1.5m formal jobs. It had had its worst yearly GDP contraction since 1990. Brazil had double-digit inflation - much above the established target - and its debt had been downgraded to junk status by major credit ratings agencies.

Military dictatorship

The economy has been so far the main threat to Ms Rousseff's presidency - an irony for someone who is a passionate economist.

The president's opponents say her handling of the economy has been highly controversial and less than stellar

She started her political career as a Marxist guerrilla in the 1970s against Brazil's brutal military dictatorship.

In the 1980s, as Brazil became a democracy, she studied economics and played a minor role in local politics in the Southern city of Porto Alegre.

Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva - president from 2003 to 2011 - then mentored her into becoming Brazil's first female head of state.

Ms Rousseff believes in the role of government in fostering development and regulating markets.

She put this belief into practice by redefining rules in many areas of the economy, including energy, oil and banking.

Now the president is facing the biggest political challenge of her life.

This has been a sharp, quick decline for Ms Rousseff and the Brazilian economy. Climbing back up will be a long, tough struggle.

- Published31 August 2016

- Published12 April 2016

- Published11 April 2016

- Published29 March 2016

- Published8 April 2018

- Published4 March 2016