Left in the dark as Venezuela's crisis deepens

- Published

There is not enough electricity for proper lighting at University Hospital, Caracas

I have seen worse conditions in a hospital. I have seen patients even more deprived of the medicines they need. But rarely have I seen an institution that appears to have gone into such steep decline as University Hospital, Caracas.

A long queue stretches from the hospital entrance as people wait in line for the lift. That's lift in the singular, because only one has been operating for the past few months.

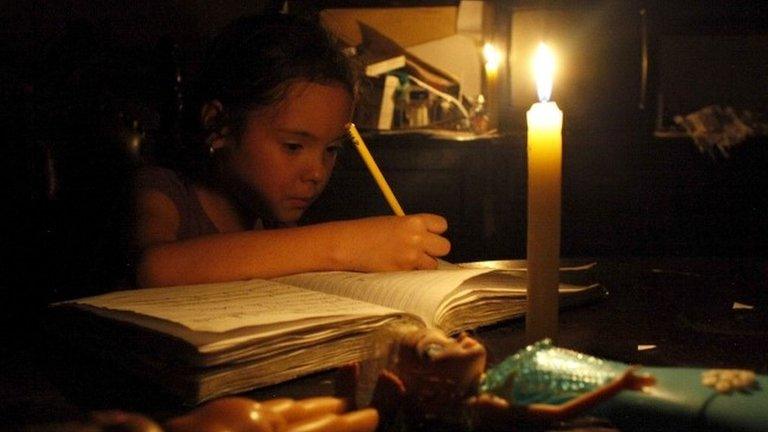

It is unclear whether the others are broken or are simply not being used because there is insufficient electrical power.

Once you reach the wards, you find there is not enough electricity even for lighting, and some of the corridors are in darkness.

Perhaps it is a good thing that the toilets and shower rooms are dark, as it provides a modicum of privacy. Cubicle doors are broken, hanging off hinges.

I saw patients on a cardiac ward forced to wash in a half-wrecked stall, with a small piece of plastic drawn across.

Dr Elizabeth Ball says there isn't even enough paper for doctors to write their reports

"We have all kinds of shortages," says Dr Elizabeth Ball, a dermatologist and teaching professor. "There are days when there is no IV solution… days when there is no anaesthetic."

Doctors are forced to use their mobile phones to record X-ray images, because there is nothing to print them on.

Venezuelan doctor: 'There are days when there's no anaesthetic'

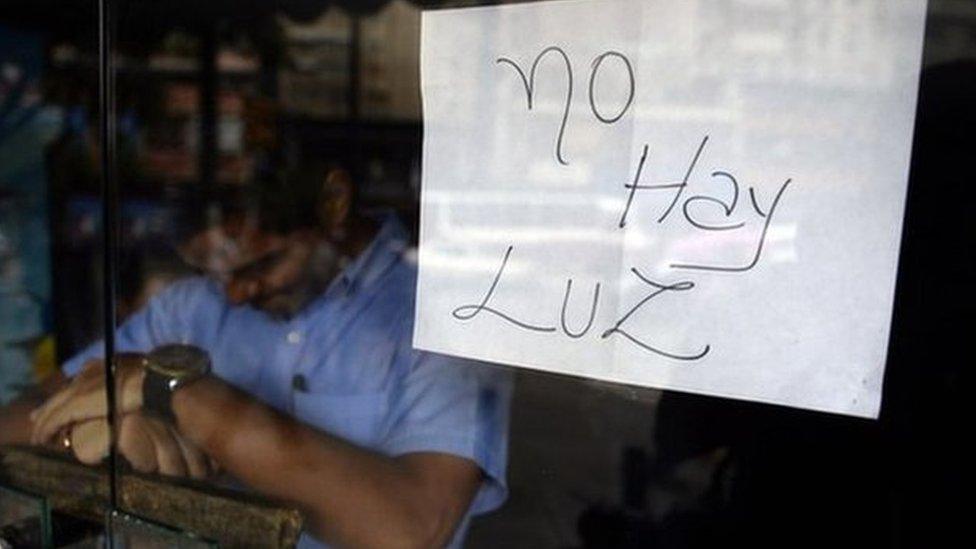

It is not just this one hospital that is in crisis or indeed Venezuela's health system as a whole. Shops have long queues outside, with basic goods in short supply, and power cuts are now a daily event across the country.

Public sector workers have been told to come in for only two days a week, in order to save energy and Venezuela's clocks have been put forward by half an hour to ensure that more of the working day takes place in daylight.

Superficially at least, the cause of these setbacks is obvious. Venezuela depends on oil exports for most of its earnings, and prices have plummeted. Meanwhile, a drought has reduced power at the hydro-electric dam that produces much of the country's electricity.

But critics of the government such as Helena Acedo refuse to accept that this is simply bad luck.

"Having a country depend on a commodity whose price is very volatile, that's bad decision making," she says. "And we know we sometimes suffer droughts. We should have invested in preparing ourselves."

Helena Acedo says the country should have been more prepared for the economic crisis it is facing

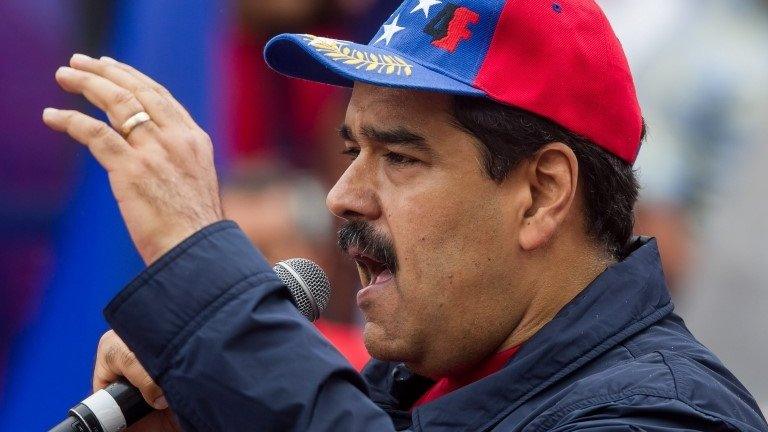

Helena was one of the many volunteers who collected signatures for a petition, demanding the recall of President Nicolas Maduro.

On Monday, the petition was handed in to the country's electoral commission, its authors claiming to have nearly two million people signed up.

If this is accepted, then a second petition will be launched and, according to the constitution, if this second one has 20% of the population on board (which would amount to about six million signatures) a referendum must be held on whether to remove the president from office.

Yet it is not just Venezuela's president who is under fire, but the ideology he represents. And the man who casts a long shadow here is Venezuela's previous president, Hugo Chavez.

"El Comandante", as he was known, spent much of his country's oil wealth on education and healthcare projects, styling himself as a champion of the poor. He also faced strong criticism from parts of Venezuela's business community for his management of the economy.

President Maduro was described as a man "for leading, for handling the most difficult situations" by his predecessor, the late Hugo Chavez

President Maduro was handpicked by Mr Chavez as his successor and promised to continue El Comandante's work.

It is that sense of continuity that is behind Valentina Figuera's loyalty to the government. We met up in a Caracas square, Plaza Diego Ibarra, which she said is an example of the renovation work carried out under Mr Chavez and continued by Mr Maduro.

"We have been facing economic problems, and that's a reality. But we have a government that is still protecting the people," she says.

Valentina Figuera remains loyal to the government, even if many Venezuelans do not

She tells me proudly how pensions are still paid, in contrast to countries in Europe where they have been cut. She talks also about the public housing projects under way, and the millions of people receiving higher and tertiary education. This is the voice of a believer who has not lost her faith.

"We could be in a worse situation… I don't think socialism is dead."

Jesus Galvez did not want to talk about socialism, or any ideology - he was just fed up. A resident of the Chacao neighbourhood of Caracas, he and his neighbours were on their third day without electricity.

They had taken to the streets in protest when what food they had went rotten because their fridges had stopped working and they had no power supply for cooking.

"It is unbelievable that we are suffering this," he says, incredulity etched on his face. He promises there will be more and bigger protests if things do not improve - that they will block the main roads if necessary.

I ask Jesus what will happen if economic conditions get worse generally in Venezuela, and he offers an unexpectedly simple answer: "There will be a civil war."

Follow Paul Moss on Twitter @BBCPaulMoss, external

- Published2 May 2016

- Published27 April 2016

- Published8 February 2016

- Published9 September 2024