Operation Condor: Landmark human rights trial reaches finale

- Published

Sara Mendez: "They took you upstairs and that's where the questioning and the torture started"

The final verdict in a historic human rights trial is expected in Argentina later on Friday. Operation Condor was a campaign of state-sponsored terror organised by South American dictatorships in the 1970s. The US-backed regimes conspired to hunt down, kidnap and kill political opponents across South America and beyond. Irene Caselli reports.

Sara Mendez escaped her native Uruguay in 1973 following the 27 June military coup. A left-wing teacher, she was considered a dangerous enemy by the newly installed regime.

She sought refuge in neighbouring Argentina, the only country in the southern area of South America that was not under military rule.

She became active in the Party for the Victory of the People (PVP), founded in 1975 by Uruguayan exiles in Buenos Aires.

But when a military coup took place in Argentina on 24 March 1976, her new home became a trap.

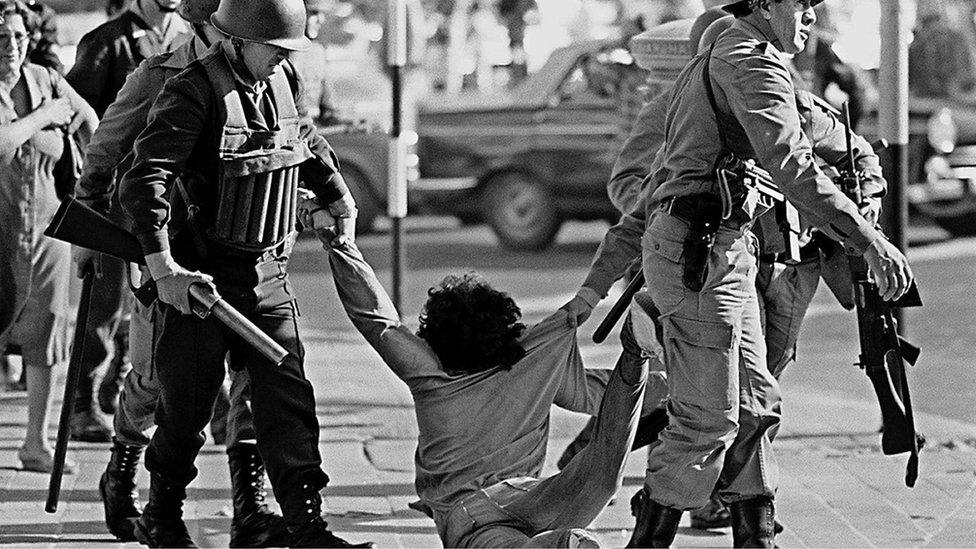

South American states colluded to crack down on left-wing opponents

On 13 July of that year, a joint commando unit of the Uruguayan and Argentine military kidnapped her and took her to an illegal detention centre.

During the operation, the commandos took her baby boy, Simon, who was only 20 days old.

"They told me not to worry, that this war was not against children, that Simon would be safe," she recalls. Simon was handed over to the family of a policeman. It took 26 years for him to find out about his real identity and for the two to be reunited.

Mendez was taken to an old car workshop in southern Buenos Aires, Automotores Orletti, which had been turned into an illegal detention centre and the operating base for Operation Condor.

"The cold was terrible but the screams were worse," remembers Mendez. "The screams of those who were being tortured were the first thing you heard and they made you shiver. That's why there was a radio blasting day and night."

Former Argentine military leaders are among those on trial

At Orletti, the Argentine and Uruguayan military tortured some 200 people, many of whom were exiles, like Mendez.

"They took you upstairs and that's where the questioning and the torture started. I think I screamed. I realised it was a sign of life, it was impossible to hold it back. And if you screamed, the others knew that you were alive," she says.

During the 1970s and 1980s, South American dictatorships came together to systematically eliminate leftist opponents. Their plan was unprecedented. It brought together the military of neighbouring nations that had previously been at war with each other in order to fight a new common enemy - the spread of Marxist ideology throughout the region.

Operation Condor was born in 1975 at a meeting of intelligence chiefs from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay.

It later came to include Brazil, and - in a more peripheral role - Ecuador and Peru. Manuel Contreras, head of Chile's feared secret police, signed the minutes of the meeting, which were later unearthed. It was named after the largest vulture in South America.

Automotores Orletti in Buenos Aires was turned into an illegal detention centre

"In trials that handle crimes against humanity there are usually few documents and they are mainly based on testimonies of survivors and families of victims," says Pablo Ouvina, the chief prosecutor in charge of the trial in Buenos Aires that has specifically focused on Operation Condor.

"In this trial there is an overwhelming quantity of documents."

Declassified documents from the United States, as well as documentation from remaining South American archives, helped the prosecutor's office put together a complicated puzzle.

"We're not talking about what happened in one detention centre or in one location in Argentina. We're talking about what happened in Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Bolivia, Paraguay and Brazil," says Ouvina.

Among the 18 defendants, who face charges of kidnapping, torture and forced disappearance, is Argentina's last dictator, Reynaldo Bignone. Since the trial started in 2013, five defendants, including Jorge Rafael Videla, the head of Argentina's junta for the first three years, have died.

Francesca Lessa says the trial is a milestone in human rights

"This is a milestone in human rights. Unlike in the past, where we had international courts, what we have here is a domestic court in Argentina which is prosecuting transnational crimes that were committed in an organised fashion by six states in Latin America," says Francesca Lessa, postdoctoral researcher at Oxford University, who has been following the trial.

For Mendez and other Uruguayans, Friday's sentence is especially symbolic because courts in their home country have never tried the ex-military for torture. Among the 18 defendants, there is also a former Uruguayan colonel, Manuel Cordero, who allegedly tortured prisoners inside Automotores Orletti.

"We want justice to be made in Uruguay too, because these were joint operations and there were Uruguayan officials that worked here too," says Mendez.

"Justice is necessary. What can we do with the truth only, if there is no space for justice?"

- Published4 June 2010