Brazil's indigenous leaders risk their lives fighting for survival

- Published

Brazil has adopted a series of measures to curb the illegal deforestation of the Amazon

Brazil's indigenous tribes are as diverse as they are numerous: from the south-western sate of Mato Grosso do Sul to the impenetrable northern jungles of the Amazon to the eastern Atlantic seaboard.

There's one thing, perhaps above all others, these tribes have in common - the relentless, insatiable pressure on their land and resources.

Indeed, there is nowhere else on earth as dangerous for "defenders" of land or the environment as Brazil.

"Home" for the Ka'apor people is a legally defined area of about 5,000 sq km in the fast diminishing forests of Maranhao in the eastern Amazon.

The tribe's numbers have recovered in recent years from a perilously low figure of 800 individuals to about 1,800 but their lives and their lands are under constant threat.

Since 2008, six Ka'apor leaders have been killed and many more have been injured for trying to protect their land from illegal loggers and miners.

One of the biggest threats comes from illegal activities

The most recent murder was that of Eusebio Ka'apor (some tribes people adopt common Brazilian names as well as their traditional titles).

Eusebio's knowledge of traditional medicines was invaluable in a community that is still wary about regular contact with "modern" Brazil. He was shot and killed in an ambush by two hooded men on a motorbike.

His killers have not been caught.

As is the case in the vast majority of murders or threats against indigenous people, the perpetrators are thought to be connected to powerful business or logging interests and, as such, enjoy the protection of corrupt public officials and law enforcement agencies.

Eusebio Ka'apor was killed in an ambush; his killers are still on the run

The Ka'apor's response to the constant threat and the inability of federal or state agents to protect them has been to rely increasingly on their own wits and resources to defend themselves.

Tribal elders have relocated some of their villages, which number only 10 in total, from the jungle interior to the fringes of their territory.

Activists say deforestation has increased recently

From there men go out on regular patrols, through the forest and along the rivers, to monitor illegal logging or mining. On rare occasions they take the law into their own hands, confronting and briefly detaining loggers then destroying their equipment.

It's a risky strategy, because the Ka'apor patrols are only lightly armed with the same small calibre rifles and machetes that they use for hunting, but it underlines the tribe's mistrust of politicians who, they say, prioritise economic development above the protection of traditional lands and peoples.

Mairusa Ka'apor: "They (illegal loggers) killed one of us here, that was a very sad day"

'Our way is the forest way'

Ka'apor elders told me that about 15% of their legally demarcated land has either been invaded or degraded (the removal of tonnes of valuable timber or the pollution of land and waterways by mining operations.)

Tribal leaders say their survival depends on these lands, which may seem sizable by comparison to the cramped modern living conditions of urban Brazil, because nearly all of their food, water and resources is sourced from the forest itself.

Much of the food used by the Ka'apor tribe comes from the forest

I'd watched earlier in the day as a group of hunters returned to the village with the day's catch, a sizeable deer cut into two and carried on their backs in baskets woven from forest plants.

Almost every part of the animal would be eaten over the next two or three days. Nothing goes to waste.

That night, after a modest meal of deer, river turtle and rice I sat down with village elders as a council of leaders from several Ka'apor communities met to discuss new reports of illegal logging within their territory.

Chief Osmar says Ka'apor members do not want a city life

"We depend on this land, the forest. It feeds us and provides us with what we need," said Chief Osmar, resplendent in a modest but colourful headdress made from feathers and beads, reflecting his position as headman of the aldeia, or village.

Defending the recent Ka'apor policy of active, rather than passive, resistance the chief said, "We don't want to live in the city - it has nothing for us. Our way is the forest way and we can't lose that, so even if our blood is spilled we will fight on."

An uphill battle

Powerful business interests and allegations of political corruption in Maranhao mean that little action is ever taken against illegal logging or mining operations at a local level.

However, the federal environmental protection agency, Ibama, does conduct targeted operations.

Brazil's federal agents have targeted illegal sawmills in the region

Several illegal sawmills on indigenous land in Maranhao were destroyed earlier this year and I've witnessed first hand as armed Ibama agents fly risky helicopter patrols into the Amazon to confront rogue logging operations.

But it's an uphill battle. Controversial Brazilian laws allow for selective cutting and export of Amazon timber. That's been ruthlessly exploited to such an extent that an estimated 80% of all wood felled and exported is done so illegally.

"In reality we're facing a situation of organised crime. There are well resourced and big financial interests driving this," says Ciclene Brito, the regional coordinator for Ibama in Maranhao.

"This problem doesn't just go away. Earlier this year we closed down 15 illegal sawmills in indigenous areas in the north of the state, but they're being re-established in many areas already," said Ms Brito.

In a major new report, external, the campaigning organization "Global Witness" says that at least 50 environmental campaigners or defenders were killed in Brazil in 2015 alone.

Last year was, says the report, "the worst year on record for killings of land and environmental defenders", not only in Brazil but also across the developing world where economic and environmental interests collide.

Findings from campaign group Global Witness show that 185 defenders of the environment were killed last year

Fleeing for their lives

It's not just indigenous communities who are losing out to unscrupulous outsiders determined to get their hands on the Amazon's valuable resources.

A day's drive from the Ka'apor territory, over dirt tracks and country roads, we're still in the state of Maranhão although the environment and climate feels more arid.

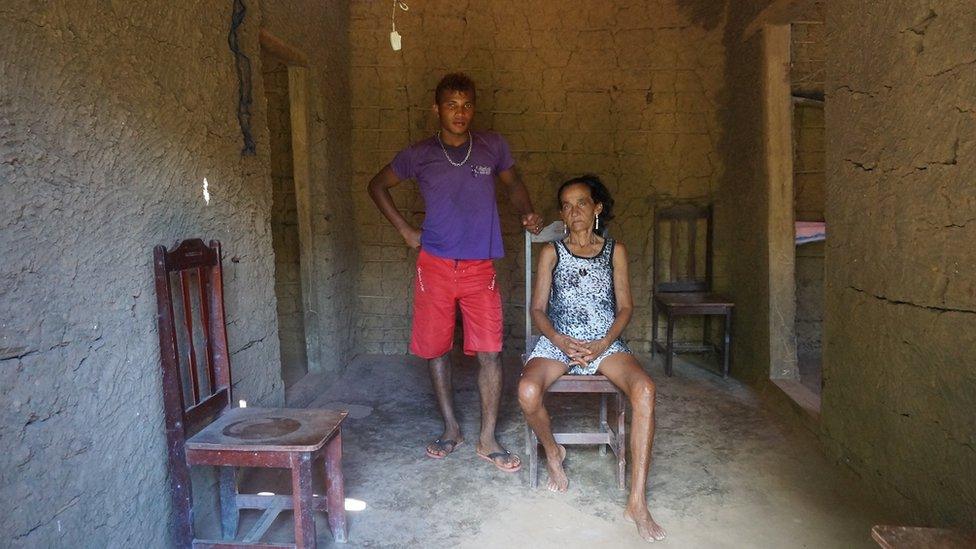

Dona Marina's husband was killed after ignoring threats to leave his land

Here, in the community of Vergel, it is small-scale farmers and peasants who are being threatened, forced from their land and, sometimes, killed.

Sitting in the entrance of the mud and bamboo shack she used to call home, Dona Marina cuts a lonely, broken figure.

She built this house with her husband, Raimundo Pereira da Silva, and here they raised a family, eking out a meagre but happy living on their smallholding on the edge of the forest.

Raimundo was shot dead by two pistoleiros (gunmen) five years ago after repeatedly ignoring threats to leave his land.

"He went out, after finishing his chores, to wash in the pond behind the house," a tearful Dona Marina tells me. "All of a sudden I heard a shot, my husband cried out. Then a second shot, then nothing."

Marina and her then 10 year-old son, who also witnessed his father's murder, fled to the nearby city soon afterwards, fearing for their own lives.

"Our lives are worthless in the city", says Dona Marina. "We didn't have much here but at least it was ours."

The community of Vergel, once about 20 families strong, has disintegrated because of the threats and violence. Destroyed houses and the small church are overgrown with scrub and have long since been abandoned.

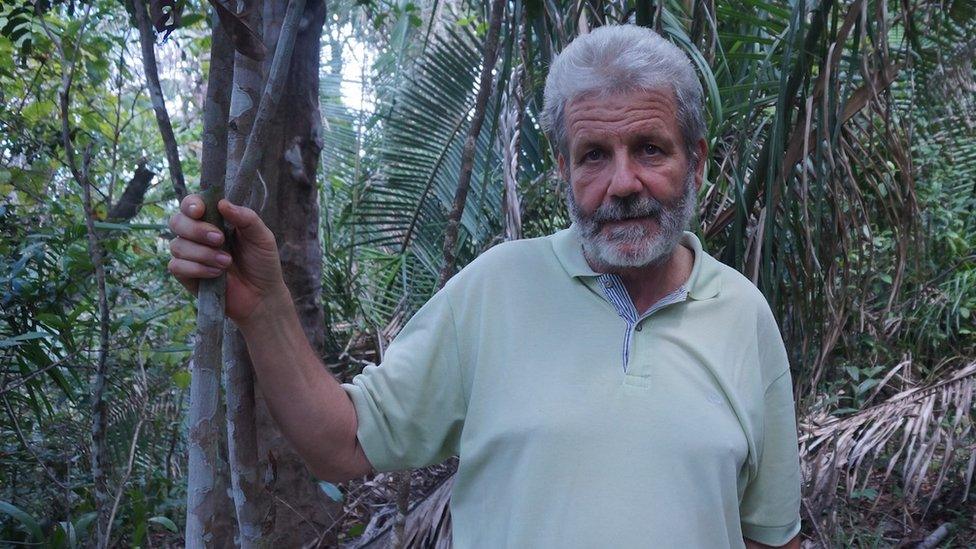

Father Jose, a German priest who has worked with these rural peasant communities for the last 25 years, says they have almost given up the fight after losing so many of their leaders, with the killers rarely being brought to justice.

Father Jose says he has also been threatened for his work with the peasants

"It's a huge problem here and across Brazil, there's complete impunity," the Father tells me.

"There's usually evidence and public information indicating who the killers are and who they were hired by but justice is slow and often is absent," says the priest who has, himself, been threatened for defending the peasants' rights.

Fighting on

Back in the Ka'apor village, they're certainly not defeated despite fresh threats against their community and open boasting by loggers that they would "soon return for the trees."

On our last night in the community, a group of village elders joined hands, danced and sang a song about the animals, the forest and their lives.

The Ka'apor tribe has less than 2,000 members

Earlier a group of indigenous children, the latest Ka'apor generation, had sung the same songs, taught to them by their fathers and mothers.

They are a tribe less than 2,000 strong with their own, verbal, unwritten language and customs. They've lost several important leaders in recent years, killed with apparent impunity, but say they have no choice other to fight on.

The Ka'apor aren't just fighting for their forest and the land they've lived on for centuries. They're fighting for their survival.

- Published5 September 2014

- Published8 September 2015