Rio 2016: Violence seeps back into city's favelas

- Published

Babilonia favela had seen business thrive before drugs gangs returned

The spectre of an Olympic Games plagued by the Zika virus may be waning, as the cold spell sweeping through southern Brazil deals with disease-carrying mosquitoes more effectively than any repellent.

But there are still many real problems and concerns for Rio 2016 organisers with two weeks before the opening ceremony in the Maracana Stadium.

The biggest of those worries is the return of violence and crime to the streets of the so-called "Marvellous City" after years of steady progress in a positive direction.

The worrying reverse is most notable in the favelas, or shantytowns, that skirt Rio's more affluent south zone.

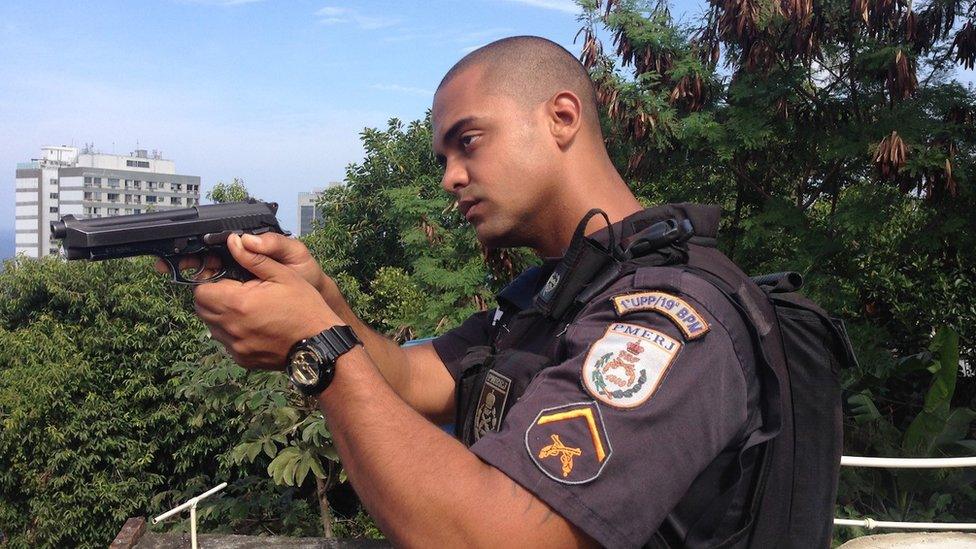

Babilonia is dangerous for police, officers say

In favelas like Santa Marta, Pavaozinho and Babilonia the much-heralded Police Pacification projects (UPP) have stalled, drugs gangs have moved back in and people are again being killed.

Safe and cool no more

Babilonia is one notable case because the favela overlooks the tourist beaches of Leme and Copacabana, where Olympic events including beach volleyball and the triathlon will take place.

Until recently it was regarded as one of the safest and coolest destinations in the city; with hillside bars overlooking the beach offering the best seafood and beer in town to visitors and steady employment for locals.

But as Lieutenant Carlos Veiga leads us on a patrol through the favela's steep, narrow alleyways, he tells me how things have deteriorated badly in recent months.

"It's dangerous, particularly at night and the gangs often shoot at our patrols," says the UPP commander here.

Police are concerned they can't guarantee security at the Rio Games

Bodies have been found in the nearby mata, or forest - the result of clashes between the two drugs gangs vying for control of the favela complex.

Locals who have enjoyed and benefited from the relative calm of recent years echo each other's concerns about a return of violence and many residents worry that after the Olympic Games the financially-broke state government will cut the pacification programme, abandoning the favelas to their fate.

If the situation is bleak in the smaller favelas like Babilonia, it can sometimes seem like all-out war in the bigger conurbations of Complexo do Alemao and Mare.

There are shootings on a daily basis, bringing a halt to traffic on the main road between the airport and the city. An eye-watering number of people - almost 2,000 - have been murdered in Rio this year already.

More than 50 police have been killed in Rio this year

Many victims of violence are killed by police, either in crossfire or shot dead by a military police force which is accused of being trigger happy and too eager to execute suspected criminals rather than arrest them.

'Welcome to hell'

But the police are victims of violence too.

"Welcome to Hell" was the slogan that greeted arriving travellers at Rio's international airport recently. The protestors were policemen, complaining about unpaid salaries and the deaths of colleagues in the city's brutal drugs wars.

"There have been more than 50 policemen and women killed this year - another one this week," says Carlos Braga.

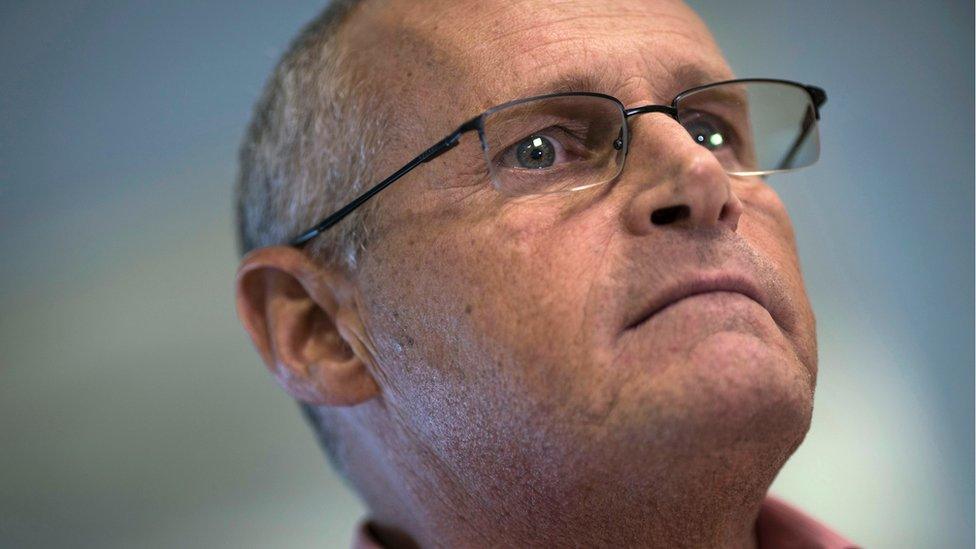

Retired police officer Carlos Braga says he cannot even guarantee his own safety

The recently retired civil police inspector added: "I am not safe. I cannot even guarantee my own safety. We police officers have to hide our badges and our guns. There will be a big amount of foreigners here yet the government can't even pay the police to protect them!"

After the city's high profile and sometimes outspoken Mayor Eduardo Paes, Rio's best known and most influential political figure is arguably Jose Mariano Beltrame.

He is the secretary of security for the state of Rio, not the city - a distinction that matters because Mr Paes recently blamed the state administration for "making a terrible mess" of the security situation.

Mr Beltrame bites his tongue when asked to respond to the mayor's accusations and is fiercely defensive of his forces' record when I ask about accusations of extrajudicial killings; but he does not hide the reality that he faces a serious financial and operational crisis.

Rio state security secretary Jose Mariano Beltrame says he is most concerned by the threat of terrorism

"Imagine if I come to you and say that you will receive only half your salary and then ask you to go out, to risk your life every day," says Mr Beltrame, who recently went out on a limb to appeal for more funds to pay for police wages.

Attack threat

The chief, who also suggested that the system was on the brink of collapse, says his biggest headache now, is not crime or violence but "terrorism".

There has not been a major international terror attack in South America since the bombing of a Jewish cultural centre in Buenos Aires 22 years ago, in which 85 people were killed.

There will be an extra 80,000 armed security personnel - a mix of soldiers and military police - on the streets of Rio and at every Olympic installation which Mr Beltrame and other officials insist will keep visitors, residents and competitors safe.

Soldiers have been drafted in to guard the city from attack

But there are worrying "gaps" everywhere.

Several troops who have come from outside the city to protect Rio have reportedly threatened to quit over appalling living conditions and unpaid salaries.

Other reports detail the last minute awarding of key security contracts to companies with little experience in the field and, as Mr Beltrame acknowledged, this is a country with 10,000 miles (16,000 km) of often porous land borders which would, theoretically, make Brazil a "soft target" for anyone seeking to disrupt the Games.

Authorities busted a gang providing Brazilian passports to Syrians

The BBC recently saw evidence demonstrating just how easy it would be to infiltrate the country after the federal police intercepted a gang that had provided more than 70 genuine Brazilian passports to Syrian nationals via corrupt officials.

Nonetheless despite largely anecdotal evidence, there is no concrete proof or threat of attack during the Olympics and the advice is that people should not be unduly worried.

Rio de Janeiro is still one of the world's most beguiling cities and will provide a stunning backdrop for the Olympics, but it has an ominously dark side too.

- Published8 April 2018

- Published20 July 2016

- Attribution

- Published15 July 2016

- Published15 July 2016

- Published14 July 2016

- Published5 July 2016