How will history look back on Rousseff's impeachment?

- Published

In 1992, senators and MPs in Brazil's Congress came together to impeach the country's first democratically elected president in almost 30 years.

Fernando Collor de Mello (simply known as Collor) had won the votes of 53% of the electorate three years earlier, but was caught in a massive corruption scandal.

Mr Collor's impeachment was a clear-cut case. There was abundant proof of bribes paid to him and a smoking gun - a car that was bought with illegal money. Also Collor was part of a small political party with weak support both from Congress and the streets.

Twenty-four years later, Brazil has for the second time impeached a president. But this time the circumstances seem far less clear cut.

Although polls suggest there is ample rejection of Dilma Rousseff as a president, the question of whether she is guilty of a crime punishable with the loss of her mandate has proven explosively controversial in Brazil.

How did things get to this point and how will history look back on the impeachment of Brazil's first woman president?

The economy

Over the course of 18 months Ms Rousseff's condemnation in a trial in the Senate went from being highly unlikely to virtually inevitable.

The seeds of her impeachment were planted in the days after her victory by a small margin in the hard-fought 2014 presidential campaign. The opposition asked for a recount of votes and accused her campaign of funding irregularities.

Meanwhile, Ms Rousseff laid out her plans for the economy, which was already deteriorating rapidly at that stage. Despite her campaign hitting hard at those who proposed an austere fiscal adjustment of spending cuts, she adopted many of the very same measures she had demonised as a candidate.

Markets initially reacted with optimism to the appointment of her new economic team, but the opposition galvanised support from those who felt betrayed by her U-turn on the economy.

The impeachment vote took place in the Brazilian Senate

That feeling burst onto the streets three months after she was re-inaugurated, with hundreds of thousands of protestors marching against her government in dozens of cities. Many similar demonstrations would be repeated in the coming weeks.

New revelations of a corruption probe into the state oil company Petrobras caused even greater damage to her Workers' Party, with her political strategist and the party's treasurer being arrested. The company had to admit losses of $2bn (£1.5bn) due to corruption.

2015 proved to be disastrous for the economy and markets soon turned against her, as a rift became clear between two key ministers with opposing views on how to fix the problems.

Inflation spiked and millions lost their jobs, after a heavy contraction in consumption and investment. In September, Brazilian bonds were downgraded to junk by one credit ratings agency. Brazil's currency lost almost half of its value and the stock market reached its lowest level in seven years.

But still no crime had been directly imputed to Ms Rousseff, despite more than 30 requests having been filed in Congress asking for her impeachment, under various allegations.

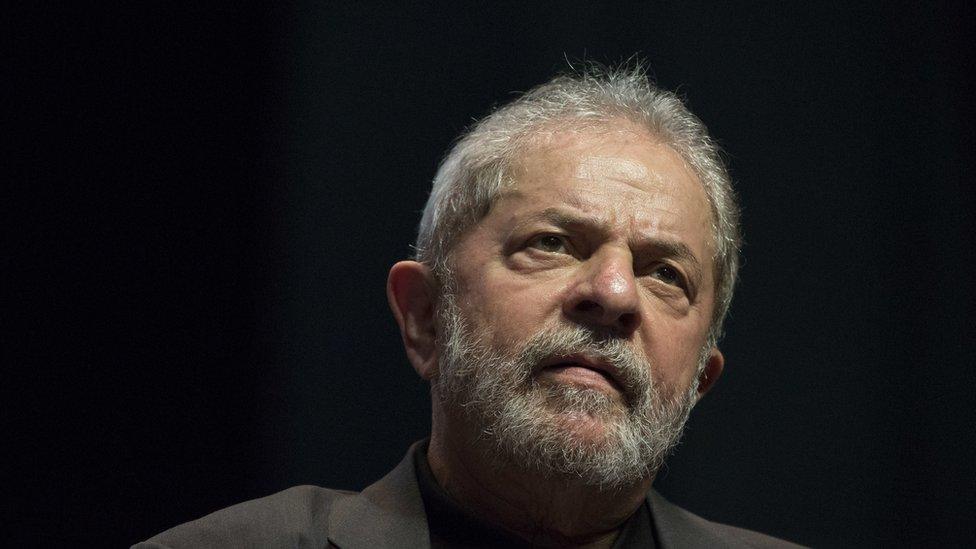

Brazil's former president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva is the subject of three investigations into alleged corruption

That changed when a fiscal court rejected her 2014 government accounts, detecting a special manoeuvre that had been used to mis-state the size of the hole in the government's budget.

Those budget problems played a key role in raising Brazil's debt and undermining the confidence in the economy.

In December, a series of unexpected political events radically shifted the course of Ms Rousseff's political future.

Up until that point she still had the support of Eduardo Cunha, the speaker of the Lower House of Congress, who had the power to accept or veto all impeachment requests against her.

Mr Cunha was being investigated in an ethics committee in Congress for allegedly having secret bank accounts. Barely hours after three MPs from Ms Rousseff's Workers' Party said they would vote against Mr Cunha in the committee, the Speaker accepted an impeachment request against the president.

Ms Rousseff was accused of being directly responsible for continuing with the use of illegal fiscal manoeuvres.

The politics

The impeachment process became a high-stakes political game.

In March 2016, Ms Rousseff's junior coalition partner - the PMDB party - abandoned her, which significantly weakened her stance in Congress. Her vice-president, Michel Temer, started his own backstage campaign for office.

In one of the most controversial moves of her career, Ms Rousseff invited former president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, into her government. The ministerial position would grant him special prosecuting privileges, as he is the subject of three investigations into alleged corruption.

A court order, based on tapped conversations between Ms Rousseff and Mr Lula, blocked his return to Brasilia and caused havoc in the political scene. On 17 April, Ms Rousseff lost her first major battle in Congress, when 367 MPs approved the impeachment proceedings against her.

The Workers' Party, that for the past 13 years had built a strong coalition in Congress, garnered only 137 votes. On 12 May, Ms Rousseff was suspended by the Senate.

The downfall

Ms Rousseff's trial in the Senate raised important questions about Brazil's democratic institutions. Was she ousted for having committed a crime - or was that just a pretext to remove a president who had lost control of the economy and politics?

Demonstrators demanding the impeachment of President Rousseff hold a banner reading "DILMA OUT!!!"

Her fiscal manoeuvres were thoroughly examined during the sessions, but it wasn't just that crime that was on trial. Her government policies, her U-turn in the economy after the election and corruption in her party were constantly part of the debate.

Also, as the trial unfolded, Michel Temer's interim government started its work in reforming the economy and outlining new policies. Senators - and Brazilians - knew that the question of condemning Ms Rousseff went beyond just deciding technically whether she was guilty or not.

It also entailed choosing between two distinct projects for Brazil - which made this impeachment process seem at times more like an election.

Brazilian society is much more fragmented and divided today than it was after Mr Collor's impeachment. Polls suggest the majority of Brazilians do not want either Ms Rousseff or Mr Temer at the helm, and would much rather see new elections - although that option was never on the table.

The question of whether history will look back on this impeachment process as a positive or negative step for Brazil now depends on how Mr Temer handles all the issues where Ms Rousseff failed since her re-election in 2014 - fixing the economy and battling corruption in the government.