Dilma Rousseff's downfall: Betrayal yes, but no coup

- Published

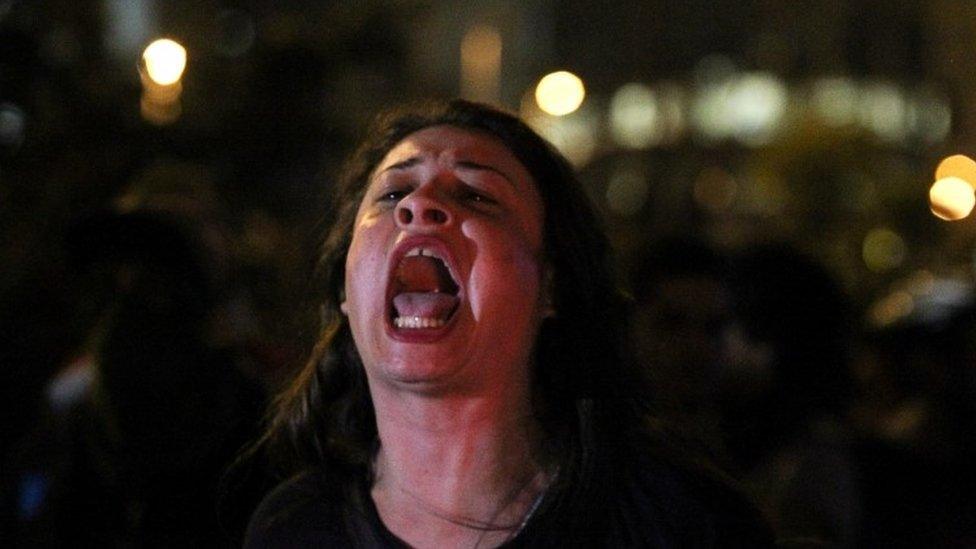

Dilma Rousseff and her supporters on the streets are adamant she is the victim of a coup

Back in the 1970s, when I first lived in Latin America and was hooked by a fascination for this region that has never left, virtually every country here was ruled by a military dictatorship.

They were brutal, inhuman regimes led by men with notorious reputations for violence and suppressing opposition - Augusto Pinochet in Chile, Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, Jorge Rafael Videla in Argentina and so on.

One of the great success stories across the region, in the intervening three or four decades, was how most of those dictatorships were driven out - usually by the overwhelming force of peaceful, popular pressure - and were replaced by elected democratic governments.

The general consensus among observers, politicians and the Latin American public is that democracy is here to stay.

That is certainly the case here in Brazil, a country that has grown into one of the world's top 10 economies, where vigorous political debate is the everyday norm and where, since the return of civilian rule in 1985, the army's place has unquestionably been back in the barracks.

Physically painful

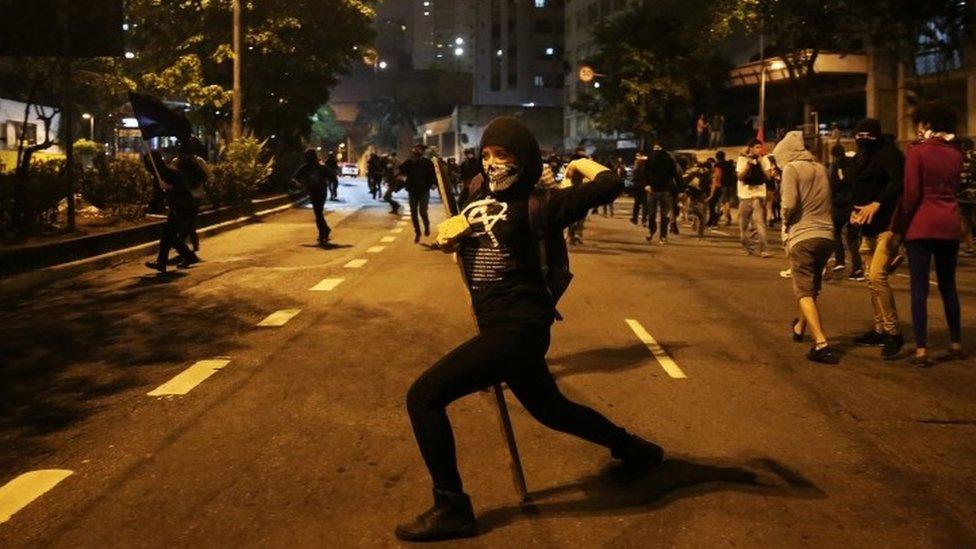

So, even in these times of social unrest and economic crisis in Brazil, there is no real threat of military intervention. But many people are describing the removal of the country's first female leader as a coup, albeit one carried out by politicians rather than generals.

Dilma Rousseff's biggest mistake was her unwillingness or inability to make the deals and alliances necessary to run an effective government in Brazil's fractured multi-party system

Despite the social unrest and economic crisis in Brazil, there is no real threat of military intervention

Many people have described the removal of the country's first female leader as a coup, albeit one carried out by politicians in the Senate (above) rather than generals

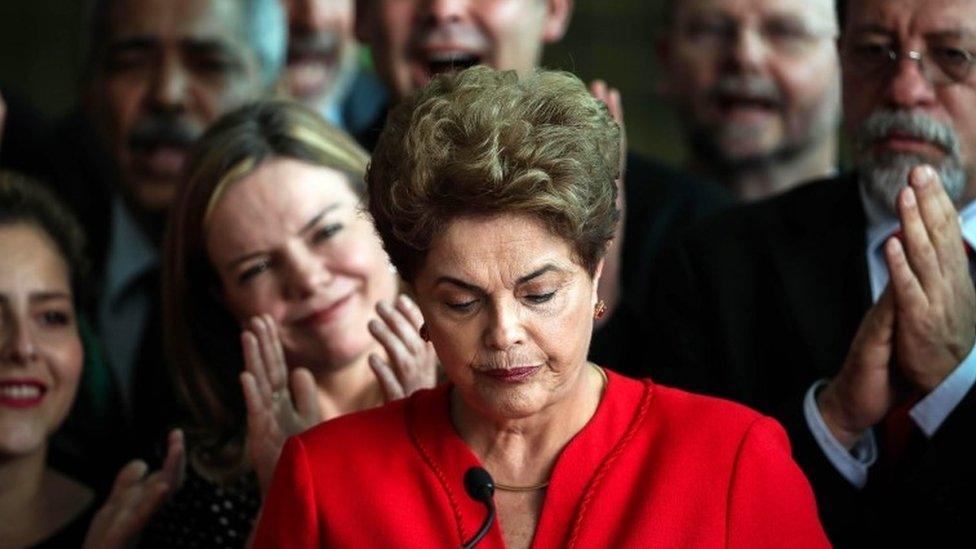

Dilma Rousseff's removal was a long drawn-out affair in which she had full legal representation

That is certainly how Dilma Rousseff herself sees things after a vote in the country's senate triggered her dismissal over charges that she illegally manipulated government accounts to hide the scale of the budget deficit.

For Ms Rousseff the experience was not as physically painful as the torture and abuse she suffered as a prisoner under the former dictatorship, but she felt just as keenly a sense of injustice and abuse of power.

Dilma Rousseff vigorously denied the charges which in the great scheme of things could be characterised as relatively minor.

She has repeatedly described the process as a plot by her political opponents to force her from office, replacing without an election a leftist, socialist government with a centre-right, market-friendly alternative.

In other words, say Ms Rousseff and her supporters also believe it was a coup.

But if the term "coup" describes a sudden and illegal seizure of power, that is arguably not what happened in Brazil.

Still the law

Dilma Rousseff's removal was a long drawn-out legal affair, overseen by the country's Supreme Court.

The army's place today is unquestionably been back in the barracks

Brazilian democracy has been damaged and sullied in the eyes of many by what happened in Brasilia over the last few days

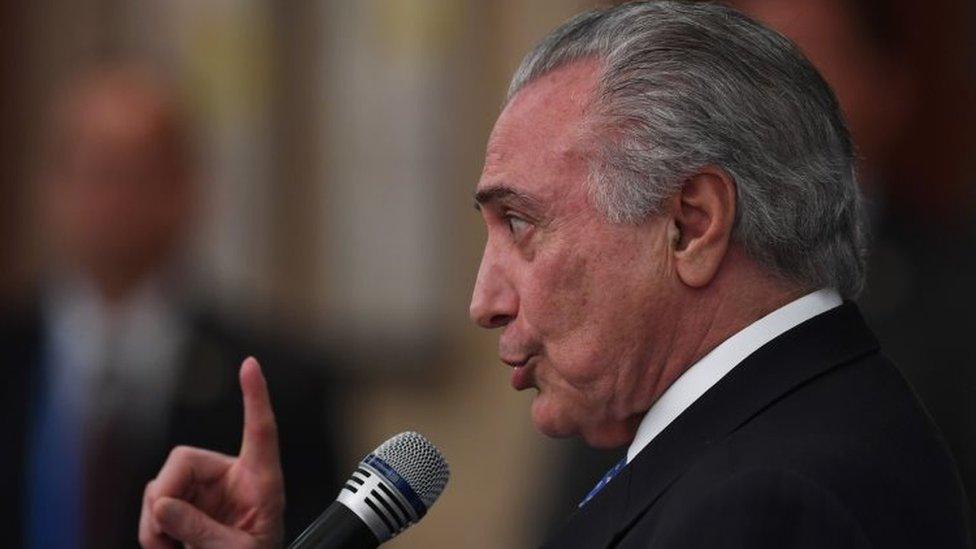

Brazil in Michel Temer now has a centre-right President who has promised to protect the popular social programmes introduced by the Rousseff/Lula governments

Impeachment is a provision laid out in the Brazilian constitution, as it is in many other democracies. As flimsy or irrelevant as many thought the charges were, the [now] former president was able to defend herself by legal argument and with counsel throughout.

The law might be an ass, but it is still the law.

Dilma Rousseff has never been formally accused of corruption or self-enrichment, unlike many of the men who have sat in judgment over her in the Brazilian Congress during the recent turbulent weeks and months.

Nor has she been implicated in the wide-ranging "car wash" corruption scandal, involving the payment of billions of dollars in bribes in relation to contracts at the state controlled oil giant, Petrobras.

Several senior politicians, including members of Ms Rousseff's own Workers Party, have been ensnared in the scandal.

Supreme Court Chief Justice Ricardo Lewandowski presided over the impeachment trial in the Senate

One widely-held belief is that the overriding concern for Brazil's well-heeled political elite is to find a way of shutting down or, emasculating, the corruption investigation before it goes any deeper.

Fernando Gabeira, once a left-wing senator but who now commentates on Brazilian politics says what has happened is "good for Brazil".

"The rules were obeyed, the constitution was considered and it means that Brazil's democracy will be stronger than before."

Others, including Gleisi Hoffman, a former minister in the last Rousseff government disagree.

She described the removal of a democratically elected leader as "a sordid and lamentable affair".

Dilma Rousseff's biggest mistake, and perhaps the real reason that she was impeached, was her unwillingness or inability to make the deals and alliances necessary to run an effective government in Brazil's fractured multi-party system.

Her last two years in office have been plagued by an economy in recession, rising inflation and unemployment.

Brazilians have become worried that many of the gains made in the first 10 years of Workers Party rule could be lost under her stewardship, in stark contrast to the years of plenty, fuelled by high oil prices, overseen by her more charismatic, politically astute and but perhaps less scrupulous predecessor, President Lula da Silva.

In the shape of Ms Rousseff's replacement and former deputy, Michel Temer, Brazil now has a centre-right president who has promised to protect the popular social programmes introduced by the Rousseff/Lula governments.

But, vowing to get the country's broken economy back on track, Mr Temer is also looking to cut government budgets and change priorities. It is a familiar conundrum and within an hour of being sworn in, the new leader was flying to China for the G-20 summit.

Brazilian democracy has been damaged and sullied in the eyes of many by what happened in Brasilia.

Back-stabbing, betrayal and the ever-present spectre of corruption? Yes. But a coup? Probably not.

- Published1 September 2016

- Published30 August 2016

- Published30 August 2016

- Published10 August 2016