Colombia peace deal: What are the most contentious points?

- Published

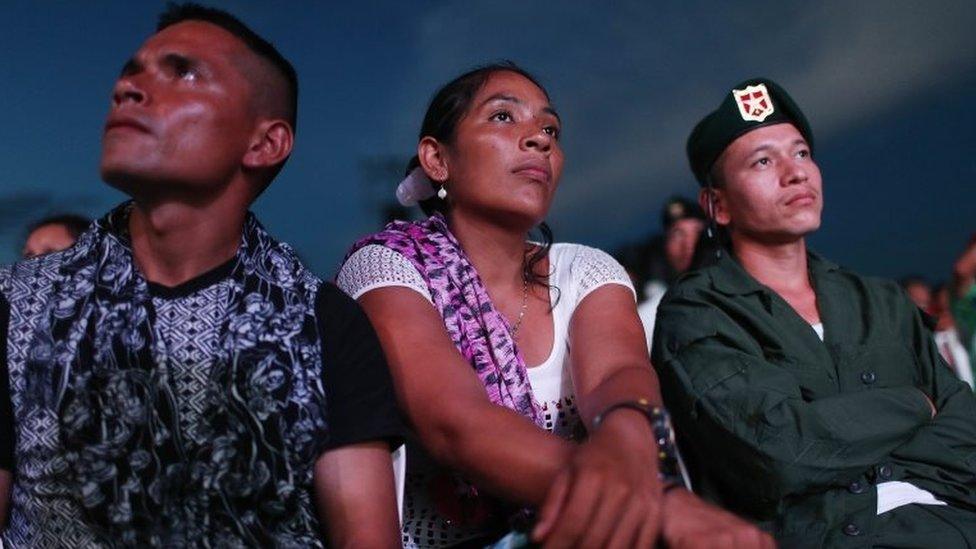

Opponents and supporters of the peace deal have been having heated arguments

The future of a peace agreement aimed at ending the longest-running armed conflict in the Americas is now in the hands of the Colombian people.

The deal, which was signed in a ceremony on Monday in the Colombian city of Cartagena, will be put to a popular vote on Sunday.

Colombians will be asked to reject or endorse the agreement reached between the government and the country's largest rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc).

The 297-page agreement will not come into force unless a simple majority of voters back it.

While it has the support of Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos and many influential international figures, including UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, there has also been significant opposition to it within Colombia.

One of the leading "no" campaigners is former President Alvaro Uribe.

Here, BBC Monitoring examines some of the reasons Colombians in the "no" camp are citing for their opposition to the deal.

Distrust of the Farc

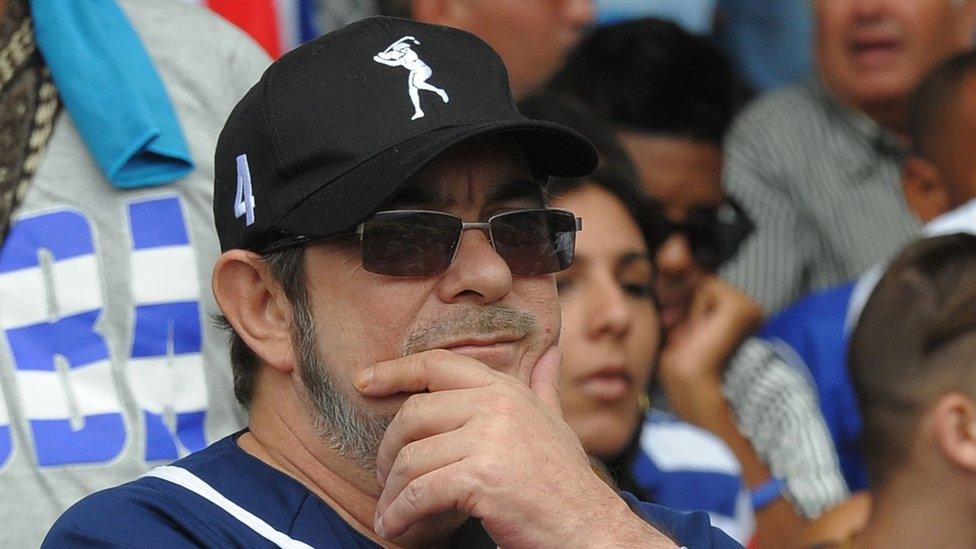

President Andres Pastrana negotiated with Farc leader Manuel Marulanda, but broke off the talks after it emerged the Farc were re-arming

This is not the first time the Colombian government has negotiated with the Farc.

In the 52 years since the Farc were founded and started fighting the Colombian government there have been several attempts at negotiating a peace deal.

However, this is the first time the two sides have reached and signed an agreement.

Previous failed attempts have made many Colombians weary of the rebels' intentions.

President Andres Pastrana, who governed from 1998 to 2002, ordered the demilitarisation of an area the size of Switzerland so that peace talks could take place there.

But after almost three years of negotiations, it transpired that the Farc had used the demilitarised zone to re-group and re-arm.

Mr Pastrana broke off the negotiations and trust in the Farc's intentions were seriously undermined for years to come.

Mr Pastrana has been campaigning against the peace agreement, calling it "a coup d'etat against justice".

Threat of 'Castro-Chavismo'

Some in Colombia accused former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez (right) of offering sanctuary to the Farc rebels

Opponents of the peace deal have accused those who back it of being in the pay of the Cuban and Venezuelan governments.

They fear that allowing the Farc rebels, who follow a Marxist ideology and who were inspired by the Cuban Revolution, to take part in politics will open the door to radical left-wing policies.

They have dubbed this threat "Castro-Chavismo" after the Cuban revolutionary leader Fidel Castro and the late Venezuelan president, Hugo Chavez.

They point to the fact that the Cuban government hosted the peace talks and Venezuela acted as a facilitator as evidence of the influence these two left-wing governments had on the negotiations.

They have accused President Santos of "selling the country out" and warn that with the rebels becoming political players, Colombia could soon resemble Cuba and Venezuela and suffer from the same shortages these countries are experiencing.

However, analysts say that Colombia is a conservative country especially when it comes to its economy and there is very little indication that this kind of shift could happen.

Impunity

Opponents of the peace deal say the rebels are "getting away with murder" and there is no justice for the victims

As part of the peace agreement, a special legal framework has been created to try those who committed crimes during the armed conflict, including Farc fighters, government soldiers and members of right-wing paramilitary groups.

Those who confess to crimes will not serve prison sentences but will take part in acts of "reparation", including clearing land mines, repairing damaged infrastructure and helping victims.

Those opposed to the deal say the rebels are "getting away with murder".

They argue that crimes against humanity and drug trafficking, which the Farc engaged in to finance itself, should be punished with jail terms.

President Santos has argued that "perfect justice would not allow peace" and that victims will receive reparation.

He denies there will be impunity, but pressure group Human Rights Watch, external says the special legal framework goes too far and the deal constitutes a "surrender of justice".

Farc 'salaries'

Farc fighters will receive financial help to ease their re-integration into civil society

Farc fighters who demobilise will receive financial aid from the state while they re-integrate into civil society.

The payments, which amount to 90% of the minimum wage, have been derided as "salaries" by opponents of the peace process.

They argue that it is unfair to reward rebels who may have murdered and kidnapped fellow Colombians while "hard-working citizens" are not given the same benefits.

Supporters of the peace deal say the rebels need financial help to ease their transition out of illegality.

BBC Monitoring, external reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter , externaland Facebook, external.

- Published24 November 2016

- Published24 November 2016

- Published24 November 2016