Mexico missing students: Unanswered questions two years on

- Published

Maricarmen Mendoza still hopes her son, Jorge Anibal Cruz Mendoza, is alive

Two years have passed since 43 students went missing on their way to a protest in the Mexican town of Iguala. The violence that night also left three dead and two injured.

At the time, their disappearance caused outrage. Protests in Mexico City turned violent. But while many are still angry, the events on the night of 26 September and the early morning of 27 September 2014 have faded.

New scandals have emerged, whether it is accusations of corruption, allegations of plagiarism or the political faux pas of inviting US Republican candidate Donald Trump to the country, President Enrique Pena Nieto now boasts the unenviable accolade of having the lowest presidential approval ratings for decades.

But the anger is still burning at the Raul Isidros Burgos rural teachers' college in Ayotzinapa, where the trainee teachers were studying.

Leaders 'corrupt'

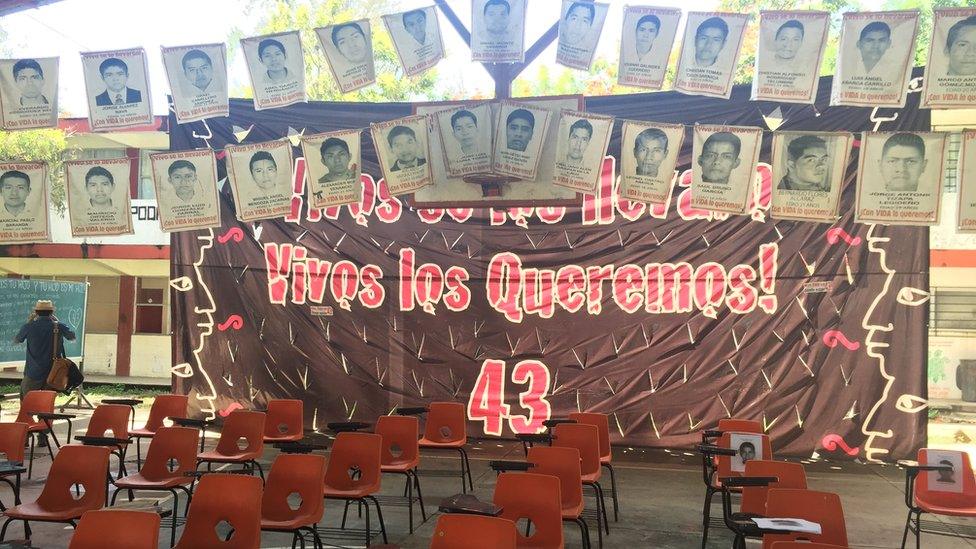

Every dormitory is adorned with reminders of their missing peers. In the college's main square, pictures of the men are tied to the railings. The basketball court in the centre has 43 chairs laid out - a shrine to the disappeared.

At the college, I meet Maricarmen Mendoza, the mother of missing student Jorge Anibal Cruz Mendoza. In her hand is a poster which reads: "He was taken alive and we want him back alive."

As a mother, she says she still has hope and is convinced the students are somewhere. She is also convinced that there was government involvement at every level. She blames President Pena Nieto for all that has happened.

"They should have given us a response by now if they were good leaders but sadly we only have corrupt leaders," she tells me.

In the college in Ayotzinapa, pictures of the missing are on display along with 43 empty chairs

She says she won't give up looking.

"Sometimes me and my friends say it's a life for a life," she says, hinting that she would go to extremes to get her son back.

In January 2015, the attorney general at the time, Jesus Murillo Karam, said the government investigation had found the "historical truth", that the students had been burned at a municipal rubbish dump after being handed over to a drugs cartel by corrupt police.

But it was a scenario that has since been rejected by several teams of experts.

A year after their disappearance, a group of independent experts appointed by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights released a report saying the government investigation was deeply flawed. Their views have since been backed up by other independent investigations.

"A lot of time was wasted trying to justify what the attorney general called the historical truth," says Carlos Zazueta of Amnesty International in Mexico City.

He says the government has not learned from its mistakes.

"It's not that they don't know what they need to do, it's that they lack any will to do it. They have been trying to save face to manage the situation in terms of the political response," he says.

History of investigations

January 2015: The government declared the "historic truth" of the facts - that the students had been burned at a rubbish dump after being handed over to drugs gangs by corrupt police

September 2015: Experts from the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights say government investigation deeply flawed.

February 2016: Argentine forensic experts conclude there's no biological or physical evidence to support government claim that the students were burned at rubbish dump

April 2016: Experts release second report that says government has hampered their investigation

July 2016: Special mechanism set up to monitor the case of missing students and follow up recommendations of the Independent Group of Experts.

More than 100 people have been detained over the students' disappearance including Iguala's Mayor Jose Luis Abarca and his wife. But Mario Patron of the Miguel Agustin Pro Juarez Human Rights Centre points out that none has been accused of forced disappearance. Instead they are detained on organised crime charges.

"It weakens the responsibility of the state," he says, adding that the municipal, state and federal levels of government are implicated in what happened that night.

And it gets worse. Many of those detained have accused authorities of torture.

"There is no consequence in this country for any breach of human rights," says Amnesty International's Carlos Zazuet.

"When they try to solve things, the methods they use breach human rights so that's the problem. It's systematic. It's the way they work, they don't seem to know any other way of working."

Just a few weeks ago, Tomas Zeron resigned as the head of Mexico's Criminal Investigation Agency. In April, the attorney general's office said he was under investigation after a team of experts presented photographic and video evidence that just a day before a charred bone fragment was found by a river, he had been at the same site - and had not reported his visit and never explained why he hadn't done so, despite saying it was not a secret.

Earlier this month, thousands marched across the capital to demand President Pena Nieto's resignation

It was a resignation that the parents of the missing students had long been asking for, but within hours he was appointed "technical secretary" of Mexico's National Security Council.

"It's a contradictory political message," says Mario Patron. "He resigns only to be given a role directly appointed by the president. We can't forget that there's an investigation under way with this civil servant and to give him a post while he is being investigated could be the build-up to a declaration of an acquittal."

What next?

In July, the Mexican government, along with the students' families agreed to a follow-up mechanism with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. They will monitor how Mexico complies with the group's recommendations.

These past two years have only served to show the systemic problem of corruption, of organised crime and of government intransigence in Mexico.

There's little faith that this year will prove more successful than the previous two.

- Published16 September 2016

- Published14 April 2016

- Published21 October 2015

- Published13 January 2015