Cuban farmers caught in 'perfect storm'

- Published

The guava - one of Cuba's most loved fruits

Nowhere in Cuba are the effects of the continuing US economic embargo more apparent than the countryside, where farming cooperatives rely on outdated tools and processing plants can't obtain spare parts, Will Grant reports.

Cubans are renowned for their sweet tooth.

This is hardly surprising on an island famed for its sugarcane and abundant in tropical fruits. And few of those fruits are more popular in Cuba than the guava.

Whether filling their favourite sugary treat - guava pastries - or turned into jams and preserves, Cubans consume tens of thousands of tonnes of guava every year.

Said by generations of Cuban grandmothers to have curative and digestive qualities, guavas thrive in the perfect balance of heat and rain found in Mayabeque province, outside Havana.

Finca Santa Rosa in the verdant municipality of Quivican is an especially good spot.

"We're looking for fruit that is mature and has a good colour," says Onil Beltran, the owner of Finca Santa Rosa, as he picks the ripest guavas from his rows of trees.

'Business is good'

The seasonal rains have left small piles of rejected fruit rotting on the ground. But recently the downpours have eased enough to allow Onil and his team to gather scores of the lime-green globes in buckets.

Even in the thick countryside of Quivican, the growth of private enterprise in Cuba is apparent. Mr Beltran's family owns around 50 hectares in total, employing 20 people as part of a state-approved private cooperative system.

The system only allows surplus produce to be sold in the open market

Business is good. Reliable figures can be hard to come by, but government statistics suggest this bucolic corner of the country saw its fruit tree harvests almost double between 2012 and 2014.

Mr Beltran's cooperative is doubtless responsible for a significant part of that improvement.

"This was just marabou [a weed] and rocks," he explains as he shows me around Finca Valverde, their second, bigger farm. "As a family we managed to turn it around."

Selling direct

For turning idle land into productive crops of mango, avocado, papaya, coffee and peanuts, the state gave the Beltrans more fields. Under the rules of the Cuban economy, they must sell their entire harvest to the state. Only the surplus can be sold in the open market.

Mr Beltran is generally happy with that arrangement as it guarantees a fixed income for him and his employees. But he is also keen to take advantage of new business opportunities as they arise.

"We can now sell direct to the tourism sector and to the hotels," he explains. "Our cooperative should start looking into that soon. It's another way for us to trade our produce."

Business is good for Onil Beltran but if the economic embargo were lifted he could modernise his farms, he says

Any trip to the countryside in Cuba - and certainly any discussion of farming methods with local people - immediately raises the issue of the decades-long US economic embargo on the island.

In the sweltering midday heat, a dozen men turn the peanut crops with long poles, flipping the plants from one side to the other so they don't bake in the sun.

19th century technology

Behind them, oxen are being used to mark out furrows for the aubergine crops and in an adjacent field, a Soviet-era tractor is still running some 40 years after it first came into Cuba.

Whether farmhand or landowner, the entire cooperative says the US economic embargo is strangling them, forcing them to rely on technology that dates to the 19th century.

"If relations continue to improve with the US and they lift the embargo, we could acquire better tools, better seeds," Mr Beltran says of the cornerstone policy of US-Cuba relations over the past six decades.

While the US and Cuba are moving towards normal relations, Congress does not want to lift the longstanding economic embargo

Earlier this year, an Alabama-based company was granted permission to sell lightweight and affordable tractors to Cuban farmers. In theory, Mr Beltran's cooperative would like to buy one but so far there is little sign of them on most farms.

Instead, he takes us to see the nearby state-run fruit processing plant.

Empty factories

Given the hard work in the fields, one would expect the factory floor at the "19th April Agricultural Products Company" to be abuzz with workers turning the fruits into preserves and jellies. But conveyor belts lie idle, machinery is switched off and crucially, no agricultural products are being processed.

The plant manager, Madeline Mendez, says they cannot source spare parts for the high-tech Italian production line the company has installed and she fears for the upcoming tomato harvest.

"We've never received a single spare part from the company in Italy," she says. "This entire production line works thanks to the inventions we've managed to make here. But some parts - for example, the digital components - can only be replaced with original pieces."

Furthermore, they are facing another problem, one borne of the perfect storm provided by the US embargo and Cuba's entangled bureaucracy.

"Our tin-can supplier is the only factory in the country which makes metal cans. Last year, it was shut down for six months because of a lack of tin and other raw materials. That has badly affected our production."

Plant manager Madeline Mendez says the factory can't source the spare industrial parts it needs

The government has promised to produce 400 million new containers soon, though most are destined for the pharmaceutical, rather than the agricultural industry.

The solution for now has been to refrigerate large vats of fruit puree until more tins arrive. But that will not last forever.

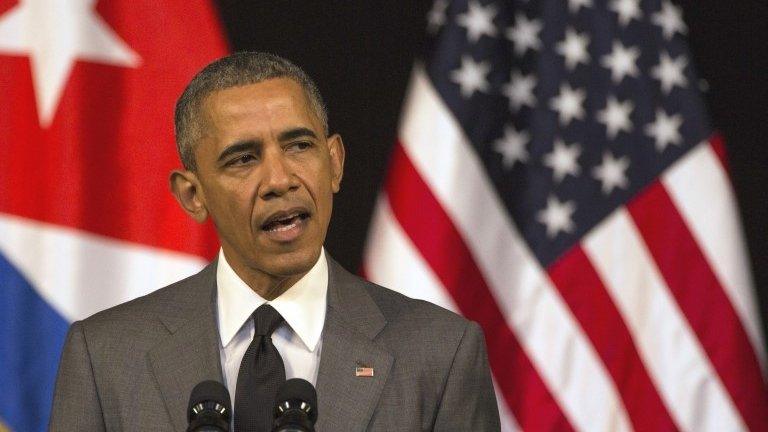

As President Obama enters his final few months in office, he will doubtless look back at the rapprochement with Cuba as one of his greatest foreign policy achievements.

While things have unquestionably improved diplomatically, most small-scale farmers on the island say the embargo must go if they are to reap the economic benefits of a changing Cuba.

- Published15 August 2016

- Published18 September 2015

- Published22 March 2016

- Published31 August 2016