Viewpoint: What next for Colombia after 'no' vote?

- Published

Those who supported the peace agreement were shocked when the result was "no"

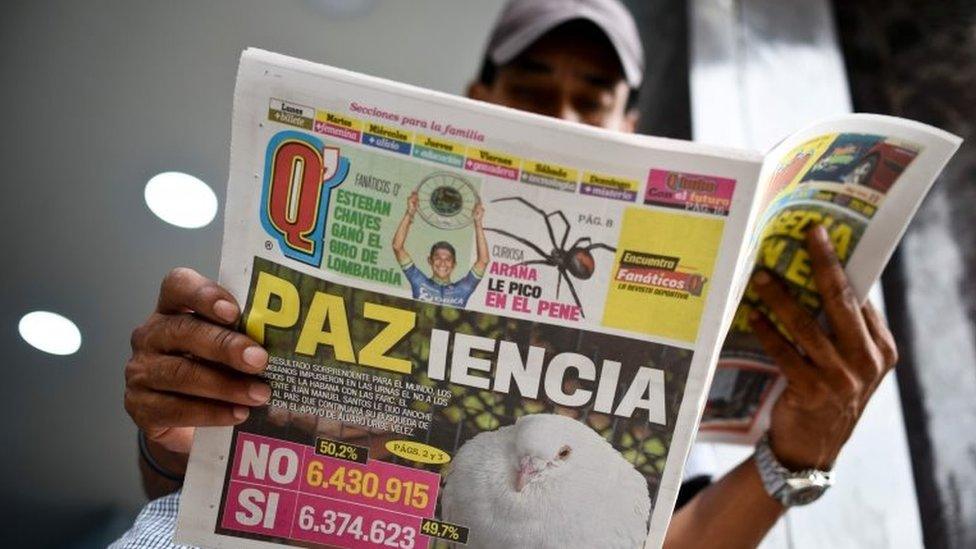

Colombians have narrowly rejected a peace agreement aimed at ending more than five decades of armed conflict. In a popular vote on Sunday, 50.2% voted against the agreement and 49.8% in favour. Juan David Gutierrez is a former adviser to the Colombian Minister of Justice. A Colombian national, he is now studying at Oxford University, where he has been fielding questions about how the deal was rejected and what may come next.

Non-Colombians have been puzzled not only by why so many Colombians have rejected the peace deal between the government and the Farc guerrilla group but also by how few turned out to vote.

At 37.4%, voter turnout was the lowest in 22 years, prompting colleagues and friends to quiz me over why so few people took part in a decision both the "yes" and the "no" camp heralded as key for the country's future.

But more immediate - and more difficult to answer - than the question of how the vote could have been "no" is the question of "what next?".

Ahead of the vote, President Santos said there was "no Plan B".

Back to the drawing board

After Colombian voters narrowly rejected the deal, both Mr Santos and the Farc rebels said they were willing to continue negotiating to reach a peace agreement a majority of Colombians would accept.

A Colombian paper urged "patience" after the deal was rejected

Clashes between the security forces and the Farc are therefore unlikely to resume.

On the other hand, the demobilisation of the rebels is not likely to progress while the agreement's future is uncertain.

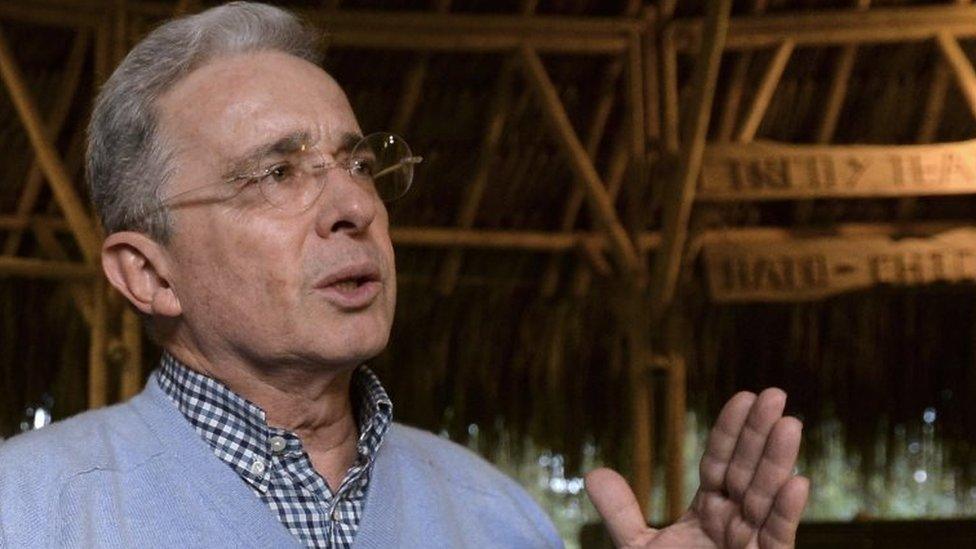

And any fresh negotiations will be complicated by the fact that there is now a third player at the table: Mr Santos' rival and leader of the "no" campaign, Alvaro Uribe.

Mr Uribe, who preceded President Santos in office, briefly outlined the topics he expected to be revised.

They included such broad issues as justice, the political participation of the rebels and social policies.

Aiming high

Following the "no" vote, the position of those backing the deal is very weak, while Mr Uribe's hand has been strengthened considerably.

Former President Alvaro Uribe led the "no" campaign

This is compounded by the fact that Mr Uribe's approval rating at 59% far outstrips that of President Santos at 38%.

While President Santos is known to be a pragmatist, he has exhausted much of his political capital.

It seems very unlikely he will be able to lead a new round of negotiations to a successful conclusion without including the leaders of the "no" camp.

The ball is therefore now in the court of those who led the "no" campaign.

And Mr Uribe is aiming high. He said that he would ask for more than just a revision of the agreement with the Farc rebels.

The former president also wants to revise the government's economic policies and even redefine the role of the family along the lines requested by religious leaders.

Stark choice

The political struggle over these issues is likely to drag on for years and will probably only be put to rest once Colombians vote in the next presidential election in 2018.

Meanwhile, Colombia is facing a political limbo arguably made more dangerous by the low number of Colombians who seem to be engaged in the political process.

The outcome of the vote has divided Colombians, some of whom were visibly distraught...

...while others celebrated in the streets.

Something is not working properly in Colombia's democracy when participating in such a historic decision as Sunday's referendum was ignored by 63% of the electorate.

But there are some who see this as a wake-up call, an opportunity for citizens to re-engage in democratic debate.

Sunday's surprise outcome has already triggered a number of citizen-led petitions urging all political leaders to continue negotiating in a more inclusive way until a peace accord is reached.

This suggests that there may be public appetite for participation in politics after all.

According to political theorist Hannah Arendt, politics is about a plurality of diverse humans agreeing on how to live together.

If she is right, Colombians will have to find a way to build a peaceful future together or Colombia will face another 52 years of conflict.