Brazil corruption: How MPs' deal could let elite off the hook

- Published

The fate of Brazil and that of Petrobras are closely intertwined

To get a good sense of how much Brazil has evolved in tackling corruption in the past few years, one can browse an old copy of those lists of "most powerful and influential people in the country" published by magazines.

If the list was published any time before 2014, it is likely that a good part of those in it are now behind bars - either sentenced or awaiting trial for corruption.

The ranks of those incarcerated is impressive:

two former ministers;

two former governors of Rio de Janeiro state, Sergio Cabral and Anthony Garotinho;

the former speaker of Congress, Eduardo Cunha;

the CEOs of all top construction firms;

the former head of the country's biggest investment bank, Andre Esteves;

the main executives of the state-oil giant Petrobras.

And that is to name just a few.

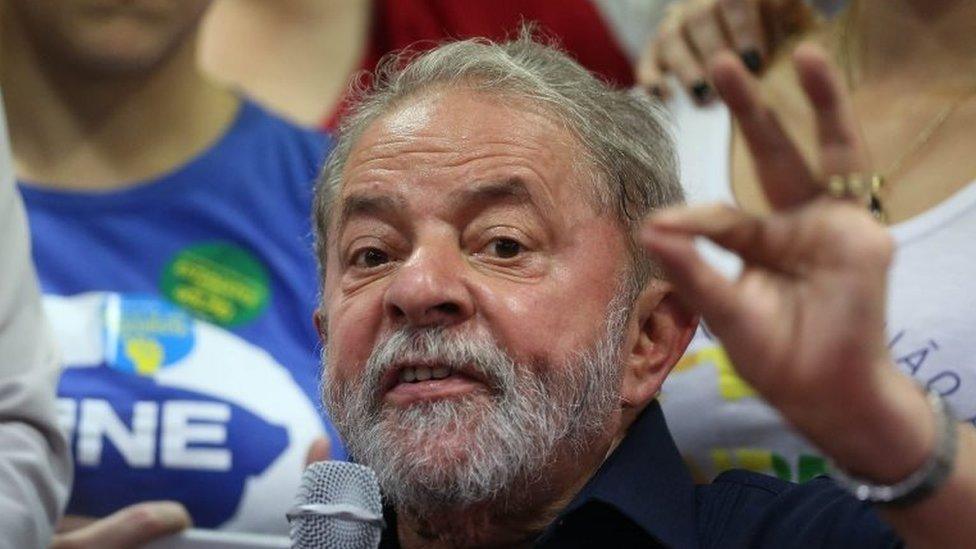

Investigations have even reached a former president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who is being tried.

Perhaps no other country in the world has so many of its powerful elite being investigated and arrested.

But it all comes with a cost.

The investigations into corruption have taken a serious toll on the country, with political instability contributing to bring down former President Dilma Rousseff earlier this year and to cause one of the worst recessions in history.

To most Brazilians, this was a price worth paying, as these investigations have brought a sense of increased transparency and justice.

But now the entire legacy of the Petrobras probe - the country's main corruption investigation that has been running for more than two years - is under threat, as members of Congress are moving to approve an amnesty that could potentially let hundreds of corrupt officials and politicians off the hook.

Read more: What has gone wrong in Brazil?

Former president Lula is one of those caught up in the investigation

For decades, construction firms who won inflated government contracts to build infrastructure have been at the heart of corruption allegations in Brazil.

Latin America's biggest construction conglomerate Odebrecht is about to sign a plea deal, and a multi-billion-dollar fine, in which it will detail how it paid vast amounts of illegal, undeclared kickbacks to electoral campaigns in exchange for contracts with Petrobras.

The Odebrecht deal has rocked Brasilia, the nation's capital.

It has been rumoured that dozens, or maybe even hundreds, of powerful politicians could be prosecuted for this practice, known as "Caixa 2" (Box Two), based on the revelations made by former Odebrecht employees.

"Caixa 2" is the way private businesses buy favours from public officials. They provide illegal, under-the-counter donations to help elect officials. Once in office, these officials return the favour by providing inflated contracts.

Members of Congress have moved fast to protect themselves from any potential prosecutions by changing crucial articles in an anti-corruption reform bill that has been discussed for months.

The bill outlines what a "Caixa 2" crime is and bans it. Up until now, current legislation had no specific articles about this practice - even though it was tackled with other existing laws.

But MPs are proposing that all past practices of such crime receive an amnesty. They will vote on the matter next week.

The way this bill is suddenly being rushed through Congress can barely hide the politicians' haste to approve it before the Odebrecht leniency deal is sealed.

Demonstrations calling for Mrs Rousseff's impeachment swept Brazil - could new protests be on the way?

The proposed amnesty has done something almost unprecedented in Brazil's Congress - it united virtually all political parties, from left to right, who had bitterly fought one another during this year's nasty impeachment trials of Ms Rousseff.

Out of 26 parties in Congress, only two are opposing the amnesty to past cases of illegal funding in campaign finances.

One of its supporters, Lower House speaker Rodrigo Maia, says the reforms are not an amnesty to "Caixa 2" practice, because "such crime does not exist in current legislation".

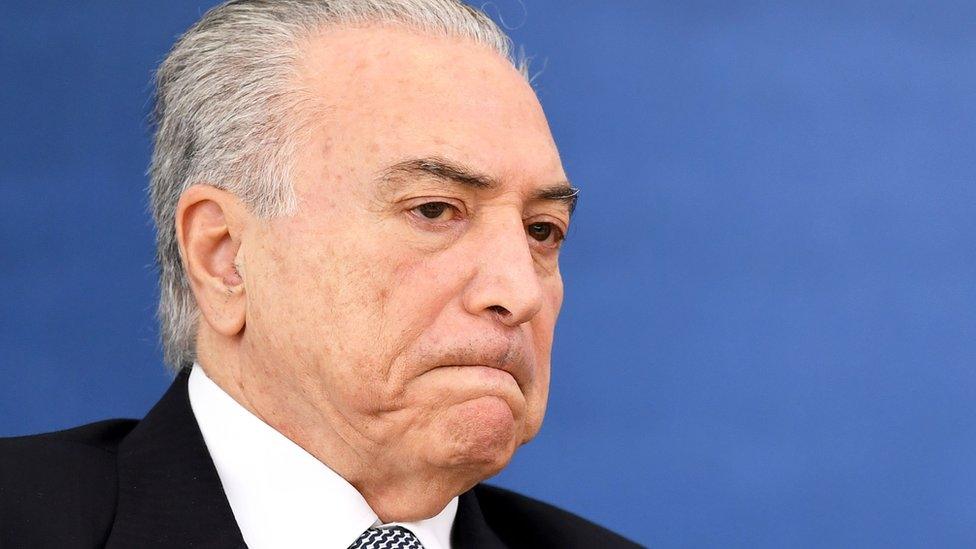

Brazil's President Michel Temer has been avoiding conflict with Congress at all cost, as he needs MPs' and senators' support to approve his tough economic reforms.

Mr Temer has said he will not interfere in these discussions - but he will have the final word if the amnesty is approved, as the bill would need to be sanctioned by him.

However, critics are keen to point out that his unwillingness to speak on such matters signals a failure of his promise to guarantee that corruption will be tackled by prosecutors and judges with no outside interference.

'A horrible message'

The backlash in the press and on social media has been enormous.

Transparency International's representative in Brazil, Bruno Brandao, says these proposals are "scandalous" and undermine the country's recent progress against corruption.

"This sends a horrible message to the rest of the world that Brazil is not serious about corruption and that its elected representatives disrespect the wishes of its own people", Mr Brandao told me.

Brazilians have long raged about corruption - it was the main point made in million-strong street protests that helped bring down Ms Rousseff earlier this year.

Many who attended those protests firmly believed that their cry against corruption would be heard by whoever led the country after the long political crisis that gripped the nation.

But current events seem to be proving them wrong.

Just last week Michel Temer's culture minister resigned, accusing the president himself of pressuring him to use his powers to favour another minister in a personal business deal.

The president denied any wrongdoing, but acknowledged he brought up the subject. Despite a public outcry and a new inquiry, the minister kept his job and the president is now under pressure from the opposition.

As efforts against corruption seem to be faltering, one wonders: Will Brazilians be back on the streets any time soon?

- Published25 November 2016

- Published8 April 2018