Argentina's Sephardic Jews mull return to Spain after 524 years

- Published

It's been more than five centuries since Spain expelled tens of thousands of members of its Jewish community, and now the country has invited their descendants to return.

But will they be tempted? Members of Argentina's Sephardic Jewish community in Buenos Aires share their thoughts on the offer.

A year after a new law came into force in Spain allowing dual citizenship for the descendants of Jews forced out of Spain in 1492, the number of applicants has been limited, with just 3,000 applications.

And Argentines came top of the list, followed by Israelis and Venezuelans.

Potential applicants have described the procedure - which involves a Spanish exam and a trip to Spain - as expensive and time-consuming. But they have also praised the fact that it no longer requires them to relinquish their existing nationality, as the previous Spanish "law of return" had.

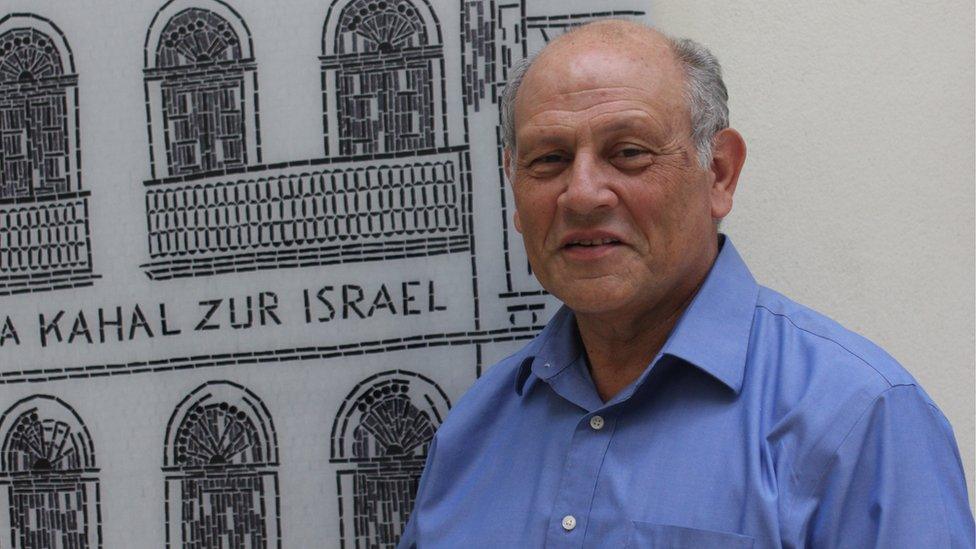

'An extraordinary reparation' - Mario Cohen, 68

"We always fought for this," says Mr Cohen, whose grandparents belonged to well-off families in Istanbul, and grew up speaking Ladino, or Judaeo-Spanish, the Romance language derived from Old Spanish and traditionally spoken by Sephardic Jews.

As head of the Centre for Investigation and Spreading of Sephardic Culture, he organises events and courses to keep Sephardic traditions alive.

"Here at this institute we feel that we are descendants of Spain," he explains. "And Spain was not recognising us."

He feels the new law represents "an extraordinary reparation".

"It was not only that we were expelled. There was also the Inquisition and for centuries the word Jew carried a lot of stigma," he says.

"It is gigantic step forward."

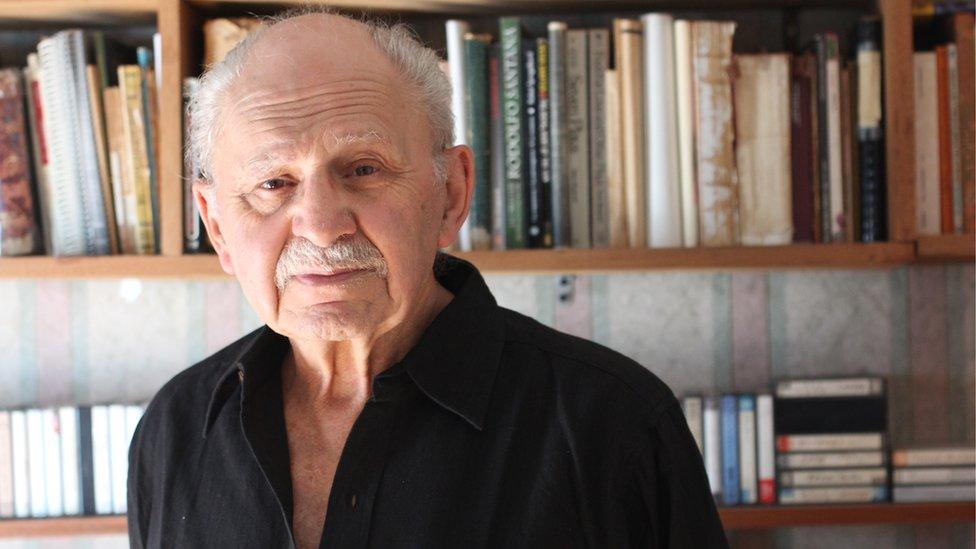

'History repeats itself' - Ricardo Halac, 81

Mr Halac, whose family is of Syrian origin, says he feels a deep connection to his Sephardic identity, and as a playwright he has often written about Jewish history.

But he is adamant he will not be applying for Spanish citizenship.

He recalls being on a bus with his father in 1945 at the age of 10. His father was reading a newspaper carrying news of the crematoriums at the concentration camp in Auschwitz and started crying.

"My father told me: 'We always need to be ready because we may need to leave again at any moment.'

"Imagine if I were to move to Spain and settle there. I would not feel at ease. History repeats itself."

A history of Sephardic Jews in Argentina

Sephardic comes from the Hebrew word Sepharad, meaning Spain

They are descendants of those who were forced out of Spain in 1492 during the Spanish Inquisition

Many moved to North Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Middle East before settling in Argentina

It is believed that between 40,000 and 70,000 Sephardic Jews live in Argentina

Spain's government has since called the expulsion a "historic mistake"

Read more: Jews invited back to Spain after 500 years

'An important gesture' - Delia Sisro, 41

"I think that it could be a great opportunity to offer my children a new citizenship," Ms Sisro says, explaining that "Jews have always had to migrate".

"It would be a backup, in case they can't live here any longer, for whatever reason," she says.

But Ms Sisro says she won't be applying for Spanish citizenship herself.

"I celebrate the decision at a political level, I think it's an important gesture," she says.

But, she continues, "I ask myself: 'Isn't it a form of betrayal to give your children a citizenship that my ancestors were denied?'"

'In bad taste' - Ezequiel Siddig, 42

Ezequiel's paternal grandparents came from Aleppo in Syria and Baghdad in Iraq, while his mother's parents came from Eastern Europe. He is a mix of Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews.

But the 42-year-old is not applying for the Spanish citizenship because he feels that "it has no meaning".

"It is an anachronistic gesture. A proper reparation would involve a thorough historic investigation carried out by the Spanish authorities to determine who are the descendants of those Jews they kicked out. More than five centuries later, it is almost of bad taste," he says.

"I don't blame those who are applying, but I feel that they forget where this comes from. My four grandparents left their respective countries because of war, Nazism or because they were starving.

"Argentina had a place for all four of them. I will stick to my Argentine citizenship."

'An act of justice' - Julie Daye, 57

Julie's grandparents were born in Aleppo. The family was traditional but did not practise religion. Julie applied for the citizenship together with her 24-year-old son Nicolas.

"Recovering the Spanish citizenship that was unjustly taken away from us Jews who for centuries kept Hispanic traditions alive is an act of justice," she says.

"Even though it does not repair what ruined and separated families suffered, it is comforting and gives the feeling that sometimes humanity learns from its mistakes. If my grandmother were alive, she would be very happy."

For Nicolas, it is also a way to discover his family's roots and gives him a chance to maybe one day live in Spain.

'Like closing a circle' - Patricia Benmergui, 54

Patricia was born to a mixed family. Her father was a Moroccan Jew, and her mother the daughter of a Spanish Catholic from the southern town of Gualchos, in the province of Granada.

Patricia tried to get her Spanish citizenship through her grandfather's documents but failed because of a spelling mistake.

When the Spanish law came up, she applied immediately.

"I was surprised that I had another opportunity to strengthen my link to Spain," she says. "I have Spanish blood from all sides.

"For me, applying for the Spanish citizenship comes from a Romantic idea. It makes me feel complete when it comes to my family history. It is like closing a circle."

- Published2 October 2015

- Published6 March 2013